Chapter 5: Music of the Classical Period

5.1 OBJECTIVES

- Identify the timeframe of the Classical Period

- Identify functions of music of the Classical Period

- Connect prominent composers of the Classical Period with well-known works.

- Recognize unique instrumentation of the Classical Period

- Critically evaluate stylistic characteristics of the Classical Period

- Synthesize music of the Classical Period with today’s culture

5.2 KEY INDIVIDUALS

- Franz Joseph Haydn

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

5.3 INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT

5.3.1 Musical Timeline

- Musical Event: 1732: Haydn born

- Musical Event: 1750: J. S. Bach dies

- Musical Event: 1756: Mozart born

- 1762: French philosopher Rousseau publishes Émile, or Treatise on Education, outlining Enlightenment educational ideas

- Musical Event: 1770: Beethoven born

- 1776: Declaration of Independence in the U.S.A

- Musical Event:1781: Mozart settles in Vienna

- Musical Event: 1787: Beethoven moves to Vienna at the age of 17 to study under Mozart, leaves almost immediately due to dying mother

- 1789: Storming of the Bastille and beginning of the French Revolution (Paris, France)

- Musical Event: 1791: Mozart dies

- Musical Event: 1791-95: Haydn travels to London

- Musical Event: 1792: Beethoven moves back to Vienna

- 1793: In the U.S.A., invention of the Cotton Gin, an innovation of the Industrial Revolution

- Musical Event: 1809: Haydn dies

- Musical Event: 1827: Beethoven dies

Of all the musical periods, the Classical* period is the shortest, spanning less than a century. Its music is dominated by three composers whose works are still some of the best known of all Western art music: Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), and Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827).

*The term “classical music” refers to art music of any period. You may have tuned in to a “Classical” music station and heard something from the Baroque or the Romantic Period. This broad category includes any music in the styles of this course, because the Classical art form has ancient Greek and Roman roots. Composers in this tradition either mastered rules of harmony, counterpoint, and other advanced musical strategies at a university or studied privately with someone who did. Folk, country, or rock musicians would not fall into this category.

Beginning towards the end of the 16th century, citizens in Europe became skeptical of traditional politics, governance, wealth distribution, and the aristocracy. Philosophers and theorists across Europe began to question these norms and issues and began suggesting instead that humanity could benefit from change. Publications and scientific discoveries of these thinkers proving and understanding many of nature’s laws spurred the change in basic assumptions of logic referred to as the Age of Reason, or the Enlightenment.

Being able to solve and understand many of the mysteries of the universe in a quantifiable manner using math and reason was empowering. Much of the educated middle class applied these learned principles to improve society. Enlightenment ideals lead to political revolutions throughout the Western world. Governmental changes such as Britain’s embrace of a constitutional democratic form of government and later the United States of America’s establishment of a democratic republic completely changed the function of a nation/state. The overall well-being and prosperity of all in society became the mission of governance.

During the enlightenment, the burgeoning middle class became a major market for art superseding the aristocracy as the principal consumer of music and art. This market shift facilitated a great demand for new innovations in the humanities. These sources provide us with reviews of concerts and published music and capture eighteenth century impressions of and responses to music.

Architecture in the late eighteenth century leaned toward the clean lines of ancient buildings such as the Athenian Parthenon and away from the highly ornate decorative accents of Baroque and Rococo design. One might also argue that the music of Haydn, Mozart, and early Beethoven aspires toward a certain simplicity and calmness stemming from ancient Greek art.

5.3.2 Music in Late Eighteenth Century

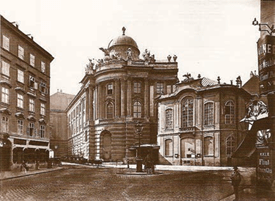

The three most important composers of the Classical period were Franz Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven. Although they were born in different places, all three composers spent the last years of their lives in Vienna, Austria, a city which might be considered the musical capitol of the Classical period (see map below).

Their musical careers illustrate the changing role of the composer during this time. The aristocratic sponsors of the Classical artists—who were still functioning under the patronage system—were more interested in the final product than in the artists’ intrinsic motivations for creating art for its own sake. For most of his life, Haydn worked for the aristocracy composing for the Esterházy family, who were his patrons. Haydn had been successful but found more freedom to forge his own career after Prince Nikolaus Esterházy’s death. Haydn was able to stage concerts for his own commercial benefit in London and Vienna. Beethoven, the son of a court musician, was sent to Vienna to learn to compose. By 1809, he succeeded in securing a lifetime annuity (a promise from local noblemen for annual support). Beethoven was not required to compose music for them; he simply had to stay in Vienna and compose. When philosophically compatible with a sponsor, the artist flourished and could express his/her creativity. In Mozart’s case, however, the patronage system was stifling and counterproductive to his abilities. Mozart was also born and raised by a father who was a court musician. It was expected that Mozart would also enter the service of the Archbishop as did his father; instead, he escaped to Vienna, where he attempted the life of a freelancer. After initial successes, he struggled to earn enough money to make ends meet and died a pauper in 1791. The journey through the Classical period is one between two camps, the old and the new: the old based upon an aristocracy with city states and the new in the rising and more powerful educated middle class.

5.4 MUSIC IN THE CLASSICAL PERIOD

5.4.1 Music Overview

Classical Music

- Mostly homophony, but with variation

- New ensembles such as the symphony* and string quartet

- Use of crescendos and decrescendos

- Question and answer (aka antecedent consequent) phrases that are shorter than earlier phrases

- Greater emphasis on musical form: for example, sonata form, theme and variations, minuet and trio, rondo, and first-movement concerto form

- Greater use of contrasting dynamics, articulations, and tempos

5.4.2 General Trends of Classical music

Musical Style

The Classical style of music embodies balance, structure, and flexibility of expression, possibly related to the noble simplicity and calm grandeur found in eighteenth-century visual art. In the music of Haydn, Mozart, and early Beethoven, we find tuneful melodies using antecedent/consequent phrasing; flexible deployment of rhythm and rests; and slower harmonic rhythm (harmonic rhythm is the rate at which the chords change). Composers included more expressive marks in their music, such as the crescendo and decrescendo. The Classical period homophony featured predominant melody lines with relatively interesting secondary lines. In the case of a symphonic orchestra or operatic ensemble, the texture might be described as homophony with multiple accompanying lines or polyphony with a single predominant melodic line.

*The word, “symphony,” holds a dual meaning as both a performing group (the symphony orchestra) and as a musical work (such as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony). We make every effort to make this clear in the text, but be aware that a “symphony” may refer to a group of instrumental performers in an orchestra or a piece of music for instruments (until Beethoven added a chorus in his Ninth Symphony) in more than two movements.

Performing Forces

The Classical Period saw new performing forces such as the piano, string quartet, and an enlarged orchestra.

The piano (earlier names were the fortepiano and then pianoforte) was capable of dynamics from soft (piano) to loud (forte); the player needed only to adjust the weight applied when depressing a key. This feature was not available in the Baroque harpsichord. Although the first pianos were developed in the first half of the eighteenth century, most of the technological advancements that led the piano to overtaking all other keyboard instruments in popularity occurred in the late eighteenth century.

The string quartet was the most popular new chamber ensemble (group of musicians with 10 or fewer performers) of the Classical Period and comprised two violins, a viola, and a cello. In addition to quartets, composers wrote duets, trios, quintets, and even sextets, septets, and octets for these stringed instruments. Whether performed in a palace or a more modest middle-class home, chamber music, as the name implies, was generally performed in a chamber or smaller room.

In the Classical period, the orchestra expanded into an ensemble that might include as many as thirty to sixty musicians distributed into four sections. The sections include the strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. Classical composers explored the individual unique tone colors of the instruments and did not treat the instrumental sections interchangeably. An orchestral classical piece utilized a much larger tonal palette and more rapid changes of the ensemble’s timbre through a variety of orchestration techniques. Each section in the classical orchestra had a unique musical purpose as penned by the composer. The string section still held prominence as the centerpiece for the orchestra. Composers predominantly assigned the first violins the melody and the accompaniment to the lower strings. The woodwinds provided diverse tone colors and were often assigned melodic solo passages. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, clarinets were added to the flutes and oboes to complete the woodwind section. To add volume and to emphasize louder dynamic, horns and trumpets were used. The horns and trumpets also filled out the harmonies. Brass instruments usually were not assigned the melody or solos. The kettle drum or timpani were used for volume highlights and for rhythmic pulse. Overall, the Classical orchestra matured into a multifaceted tone color ensemble that composers could utilize to produce their most demanding musical thoughts acoustically through an extensive tonal palette. General differences between the Baroque and Classical (1750-1815) orchestras are summarized in the following chart.

Baroque Orchestras

- Strings at the core

- Woodwind and brass instruments such as the flutes or oboes and trumpets and horns doubled the themes played by the strings or provided harmonies

- Any percussion was provided by timpani

- Harpsichord, sometimes accompanied by cello or bassoon, provided the basso continuo

- Generally led by the harpsichord player

Classical Orchestras

- Strings at the core

- More woodwind instruments— flutes and oboes and (increasingly) clarinets—which were sometimes given their own melodic themes and solo parts

- More brass instruments, including, after 1808, trombones.

- More percussion instruments, including cymbals, the triangle, and other drums

- Phasing out of the basso continuo

- Generally led by the concertmaster (the most important first violinist) and increasingly by a conductor

Emergence of New Musical Venues

The Classical period saw performing ensembles like the orchestra appearing at more concerts. These concerts were typically held in theaters or in the large halls of palaces and attended by anyone who could afford the ticket price, which was reasonable for a substantial portion of the growing middle class. For this reason, the birth of the public concert is often traced to the late eighteenth century. At the same time, more music was incorporated into a growing number of middle-class households.

The redistribution of wealth and power of this era affected the performing forces and musical venues in two ways. First, although the aristocracy still employedmusicians,professionalcomposerswerenolongerexclusivelyemployedby the wealthy. This meant that not all musicians were bound to a particular person or family as their patron/sponsor. Therefore, public concerts shifted from performances in the homes and halls of the rich to performances for the masses held in halls or churches that could house large groups of people. Second, middle class families incorporated more music into their households. As the piano found its way into these homes, both women and children began taking lessons and performing on the small, home stage. Musicians could now support themselves through teaching lessons, composing and publishing music, and performing in public venues, such as in public concerts. Other opportunities included church music, still a popular avenue, and the public opera house, which was the center for vocal music experimentation during the Classical era.

5.5 MUSIC OF FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809)

Born in 1732, Haydn grew up in a small village about a six-hour coach ride east of Vienna (today the two are about an hour apart by car). His family loved to sing together, and perceiving that their son had musical talent, presented him to a relative who was a schoolmaster and choirmaster. As an apprentice, Haydn learned harpsichord and violin and sang in the church. So distinct was Haydn’s voice that he was recommended to Vienna’s St. Stephen’s Cathedral’s music director. In 1740 Haydn became of student of St. Stephen’s Cathedral and sang with the St. Stephen’s Cathedral boys’ choir for almost ten years, until his voice broke (changed). He moved on to become valet to the Italian opera composer Nicola Porpora and most likely started studying music theory and music composition in a systematic way at that time. He composed a comic musical and eventually became a chapel master for a Czech nobleman. When this noble family fell into hard times, they released Haydn. In 1761, he became a Vice-Chapel Master for an even wealthier nobleman, the Hungarian Prince Esterházy. Haydn spent almost thirty years working for their family. He was considered a skilled servant, who soon became their head Chapel Master and was highly prized, especially by the second and most musical of the Esterházy princes for whom Haydn worked.

The Esterházys kept Haydn very busy: he wrote music, which he played both for and with his patrons, ran the orchestra, and staged operas. In 1779, Haydn’s contract was renegotiated, allowing him to write and sell music outside of the Esterházy family. Within a decade, he was the most famous composer in Europe. In 1790, the musical Prince Nikolaus Esterházy died, and his son Anton downsized the family’s musical activities. This shift allowed Haydn to accept an offer to give a concert in London, England, where his music was very popular. Haydn left Vienna for London in December. For the concerts there, he composed opera, symphonies, and chamber music, all of which were extremely popular. Haydn revisited London twice in the following years, 1791 to 1795, earning—after expenses—as much as he had in twenty years of employment with the Esterházys. Nonetheless, a new Esterházy prince decided to reestablish the family’s musical foothold, so Haydn returned to their service in 1796. In his last years, he wrote two important oratorios (he was impressed by performances of Handel’s oratorios while in London) and more chamber music.

5.5.1 Overview of Haydn’s Music

Like his younger contemporaries Mozart and Beethoven, Haydn composed in all the genres of his day. From an historical perspective, his contributions to the string quartet and the symphony are particularly significant: in fact, he is often called the Father of the Symphony. His music is also known for its motivic construction, use of folk tunes, and musical wit. Central to Haydn’s compositional process was his ability to take small numbers of short musical motives and vary them in enough ways so as to provide interesting music for movements that were several minutes long. Folk-like as well as popular tunes of the day can be heard in many of his compositions for piano, string quartet, and orchestra. Several of his compositions play on the listeners’ expectations, especially through surprise rests, sustained notes, and sudden dynamic changes.

Focus Composition: Haydn, Symphony No. 94 in G major, “Surprise”

Haydn is also often called the Father of the Symphony because he wrote over 100 symphonies, which span most of his compositional career. The symphony gradually took on the four-movement form that was a norm for over a century, although as we will see, composers sometimes relished departing from the norm. Haydn’s symphonic orchestra featured the strings section, with flutes and oboes for woodwinds, trumpets and horns for brass, and timpani for percussion.

Haydn wrote some of his most successful symphonies in London. His Symphony No. 94 in G Major, which premiered in London in 1792, is a good example of Haydn’s thwarting musical expectations for witty ends. Like most symphonies of its day, the first movement is in sonata form. Expect a couple of opening themes that you will hear again, then a middle section that moves away from stability, and then a return to those opening themes. Haydn’s second movement marked “Andante” (a walking pace) is atypical theme and variations movement consisting of a musical theme that the composer then varies several times. Each variation retains enough of the original theme to be recognizable but adds other elements to provide interest. The themes used for theme and variations movements tended to be simple, tuneful melody lines.

LISTENING GUIDE

Performed by The Orchestra of the 18th Century, conducted by Frans Brüggen.

- Composer: Haydn

- Composition: Symphony No. 94 in G major, “Surprise” (II. Andante)

- Date: 1791

- Genre: symphony

- Form: II. Andante is in theme and variations form

- Performing Forces: Classical orchestra here with 1st violin section, 2nd violin section, viola section, cellos/bass section, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 trumpets, 2 horns, 2 bassoons, and timpani

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is in theme and variations form

- The very loud chord that ends the first phrase of the theme provides the “surprise”

Other things to listen for:

- The different ways that Haydn varies the theme: texture, register, instrumentation, key

Table 1: Listening Guide for Symphony No. 94 in G major, “Surprise” (II. Andante)

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 8:46 | Theme: aa | Eight-measure theme with a question and answer structure. The “question” ascends and descends and then the “answer” ascends and descends, and ends with a very loud chord (the answer). In C major and mostly consonant. In homophonic texture, with melody in the violins and accompaniment by the other strings; soft dynamics and then very soft staccato notes until ending with a very loud chord played by the full orchestra, the “surprise.” |

| 9:21 | b | Contrasting more legato

eight-measure phrase ends like the staccato motives of the a phrase without the loud chord; |

| 9:39 | b | Repetition of b |

| 9:57 | Variation 1: aa | Theme in the second violins and violas under a high-

er-pitched 1st violin countermelody. Still in C major and mostly consonant Ascending part of the theme is forte and the descending part of the phrase is piano; the first-violin countermelody is an interesting line but the overall texture is still homophonic |

| 10:30 | bb | Similar in texture and harmonies; piano dynamic throughout |

| 11:05 | Variation 2: aa | The first four measures are in unison monophonic texture and very loud and the second four measures (the answer) are in homophonic texture and very soft; In C minor |

| 11:41 | Develops motives from a and b phrases | In C minor with more dissonance; very loud in dynamics; The motives are passed from instrument to instrument in polyphonic imitation. |

| 12:20 | Variation 3: aa | Back in C major.

The oboes and flutes get the a phrase with fast repeated notes in a higher register; the second time, the violins play the a phrase at original pitch; uses homophonic texture through- out. |

| 12:56 | bb | The flutes and oboes play countermelodies while the strings play the theme. |

| 13:27 | Variation 4: ab | The winds get the first a phrase and then it returns to the first violin; very loud for the first statement of a and very soft for the second statement of a; homophonic texture throughout. |

| 14:01 | bb + extension | Shifting dynamics |

| 14:50 | Coda |

Why did Haydn write such a loud chord at the end of the repeated theme so early in the piece? Commentators have long speculated that Haydn may have noticed that audience members tended to drift off to sleep in slow and often quietly lyrical middle movements of symphonies and decided to give them an abrupt wakeup. Haydn clearly intended to play upon his listener’s expectations in ways that might even be considered humorous.

Haydn’s symphonies greatly influenced the musical style of both Mozart and Beethoven; indeed, these two composers learned how to develop motives from Haydn’s earlier symphonies. Works such as the Surprise Symphony were especially impressive to the young Beethoven, who, as we will later discuss, was taking music composition lessons from Haydn about the same time that Haydn was composing the Symphony No. 94 before his trip to London.

5.6 MUSIC OF WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (b. 1756-91) was born in Salzburg, Austria. His father, Leopold Mozart, was an accomplished violinist of the Archbishop of Salzburg’s court. Additionally, Leopold had written a respected book on the playing of the violin. At a very young age, Wolfgang began his career as a composer and performer. A prodigy, his talent far exceeded any in music, past his contemporaries. He began writing music before age five. At the age of six, Wolfgang performed in the court of Empress Maria Theresa.

Mozart’s father was quite proud of his children, both being child prodigies. At age seven, Wolfgang, his father, and his sister Maria Anna (nicknamed “Nannerl”) embarked on a tour featuring Wolfgang in London, Munich, and Paris. As was customary at the time, Wolfgang, because he was the son, was promoted and pushed ahead with his musical career by his father. The sister, being female, grew up traditionally, married, and eventually took care of her father Leopold in his later years. However, the two siblings performed when Wolfgang was between the ages of six and seventeen. The tours, though, were quite demeaning for the young musical genius in that he was often looked upon as just a superficial genre of entertainment rather than being respected as a musical prodigy. He would often be asked to identify the tonality of a piece while listening to it or asked to sight read and perform with a cloth over his hands while at the piano. Still, the tours allowed young Mozart to accumulate knowledge about musical styles across Europe. As a composer prior to his teens, the young Mozart had already composed religious works, symphonies, solo sonatas, an opera buffa, and Bastien and Bastienne, an operetta; in short, he had quickly mastered all the forms of music.

Back in Salzburg, Mozart was very unhappy with the restrictions of his patron the Archbishop of Salzburg, Hieronymus von Colloredo. Mozart also felt the need to garner independence from his father. Though Leopold was well-meaning and had sacrificed a great deal to ensure the future and happiness of his son, he was an overbearing father. By age twenty-five, Mozart moved to Vienna, became a free artist (agent), and married Constance Weber. Mozart’s father did not view the marriage favorably and this marriage served as a wedge severing Wolfgang’s close ties to his father.

Wolfgang’s new life in Vienna was not easy. For almost ten years, he struggled to find the secure financial environment in which he had grown up. The patronage system was still the primary avenue for musicians to prosper. Mozart often was considered for patron employment but was not hired. Having hired several other musicians ahead of Mozart, Emperor Joseph II hired Mozart simply to compose dances for the court’s balls. As the tasks were far beneath his musical genius, Mozart was quite bitter about this assignment.

While in Vienna, Mozart relied on his teaching to sustain him and his family. He also relied on the entertainment genre of the concert. He wrote piano concertos for annual concerts. Programs also included some arias, solo improvisation, and occasionally an overture of piece by another composer.

The peak of Mozart’s career success occurred in 1786 with the writing of The Marriage of Figaro (libretto by Lorenza da Ponte). The opera was a hit in Prague and Vienna. The city of Prague, so impressed with the opera, commissioned another piece by Mozart. Again with da Ponte as librettist, he composed Don Giovanni. The second opera left the audience somewhat confused. Mozart’s luster and appeal seemed to have passed. As a composer, Mozart was trying to expand the spectrum, or horizons, of the musical world. Therefore, his music sometimes had to be heard more than once by the audience for them to understand and appreciate it. Mozart pushed the boundaries of the expected entertainment of his aristocratic audience, and patrons in general did not appreciate it. In a letter to Mozart, Emperor Joseph II wrote of Don Giovanni (audio in this chapter) that the opera was perhaps better than The Marriage of Figaro but that it did not set well on the pallet of the Viennese. Mozart quickly fired back, responding that the Viennese perhaps needed more time to understand it.

In the final year of his life, Mozart with librettist (actor/poet) Emanuel Schikaneder, wrote a very successful opera for the Viennese theatre, The Magic Flute. The newly acclaimed famous composer was quickly commissioned to write a piece for (and was invited to attend) the coronation of the new Emperor, Leopold II, as King of Bohemia. The festive opera that Mozart composed for this event was called The Clemency of Titus. Its audience, overly indulged and exhausted from the coronation, was not impressed with Mozart’s work. Mozart returned home depressed and broken, and began working on a Requiem, which, coincidentally, would be his last composition.

The Requiem was commissioned by a Count who intended to pass the work off as his own. Mozart’s health failed shortly after receiving this commission and the composer died before completing the piece – just before his thirty sixth birthday. Mozart’s favorite student, Franz Xaver Sűssmayr, completed the mass from Mozart’s sketch scores, with some insertions of his own, while rumors spread that Mozart was possibly poisoned by another contemporary composer. In debt at the time of his death, Mozart was given a common burial. As one commentator wrote:

Thus, “without a note of music, forsaken by all he held dear, the remains of this Prince of Harmony were committed to the earth, not even in a grave of their own, but in the common fosse affected to the indiscriminate sepulture of homeless mendicants and nameless waifs.”[1]

5.6.1 Overview of Mozart’s Music

From Mozart’s youth, his musical intellect and capability were unmatched. His contemporaries often noted that Mozart seemed to have already heard, edited, listened to, and visualized entire musical works in his mind before raising a pen to compose them on paper. When he took pen in hand, he would basically transcribe the work in his head onto the manuscript paper. Observers also said that Mozart could listen and carry on conversations with others while transcribing his music to paper.

Mozart was musically very prolific in his short life. He composed operas, church music, a Requiem, string quartets, string quintets, mixed quintets and quartets, concertos, piano sonatas, and many lighter chamber pieces (such as divertimentos), including his A Little Night Music (Eine kleine Nachtmusik). His violin and piano sonatas are among the most popular pieces still performed in this genre. Six of his quartets were dedicated to Haydn, whose influence Mozart celebrated in their preface.

Mozart wrote exceptional keyboard music and was respected as one of the finest pianists of the Classical period. He loved the instrument dearly and wrote many solo works, as well as more than twenty piano concertos for piano and orchestra, thus contributing greatly to the concerto’s popularity as an acceptable medium. Many of these concerti (Italian plural for “concerto”) were premiered at Mozart’s annual public fundraising concerts.

Mozart composed more than forty symphonies, the writing of which extended across his entire career. He was known for full and rich instrumentation conveying much emotion. His final six symphonies were written in the last decade of his life. These include the Haffner in D (1782), the Linz in C (1783), the Prague in D (1786), and his final symphony, the Jupiter (audio in this chapter) in C (1788). Mozart’s final symphony likely was not performed prior to his death. In addition to the symphonies and piano concertos, Mozart composed other major instrumental works for clarinet, violin and French horn in concertos.

Focus Composition: Mozart, Don Giovanni [1787]

LISTENING GUIDE

- Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Librettist: Lorenzo Da Ponte

- Composition: Deh, vieni alla finestra, Testo (Aria) from Don Giovanni, in Italian

- Date: 1787, First performed October 29, 1787

- Genre: Aria for baritone voice

- Form: binary

- Nature of Text: Originally in Italian Translation from Italian to English

- Performing Forces: Baritone and Classical Orchestra

What we want you to remember about this composition:

This is a beautiful love-song where the womanizer Don Giovanni tries to woo Elvira’s maid. The piece in D major begins in a 6/8 meter. The musical scoring includes a mandolin in the orchestra with light plucked accompaniments from the violins which supplement the feel of the mandolin. The atmosphere created by the aria tends to convince the audience of a heartfelt personal love and attraction The piece is written in a way to present a very light secular style canzonetta in binary form, which tends to help capture the playfulness of the Don Giovanni character.

Other things to listen for:

This piece could very easily be used in a contemporary opera or musical.

Focus Composition: Mozart, Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551 (1788)

Like Haydn, Mozart also wrote symphonies. Mozart’s final symphony, the Symphony No. 41 in major, K. 551 is one of his greatest compositions. It very quickly acquired the nickname “Jupiter,” a reference to the Greek god, perhaps because of its grand scale and use of complex musical techniques. For example, Mozart introduced more modulations and key changes in this piece than was typical. The symphony opens with a first movement in sonata form with an exposition, development, and recapitulation. Listen to the first movement with the listening guide below.

LISTENING GUIDE

- Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Composition: Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551 — 1st Movement, Allegro Vivace

- Date: 1788

- Genre: Symphony

- Form: Sonata form

- Performing Forces: Classical orchestra

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- Listen to the different sections identified in sonata form.

- During the development section you will feel the instability of the piece induced by the key changes and ever-changing instrument voicings.

Other things to listen for:

- Its melodic line is mostly conjunct.

- Its melody contains many melismas.

- It has a Latin text sung in a strophic form.

I: Allegro Vivace

Table 2: Listening Guide for Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551 — 1st Movement, Allegro Vivace

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Full orchestra.

Stated twice-First loud and then soft short responses. |

EXPOSITION: Opening triplet motive |

| 0:18 | The forte dynamic continues, with emphasis on dotted rhythms.

Winds perform opening melody followed by staccato string answer; Full bowed motion in strings. |

First theme in C major |

| 1:30 | Motive of three notes continues; Soft lyrical theme with moving ornamentation in accompaniment. | Pause followed by second theme of the exposition |

| 2:08 | Sudden forte dynamic. Energy increases until sudden softening to third pause;

Brass fanfares with compliment of the tympani. |

Second Pause followed by transition to build tension |

| 2:41 | Theme played in the strings with grace notes used.

Melody builds to a closing; A light singable melody derived from Mozart’s aria “Un baccio di mano” |

After the third pause, the third theme is introduced |

| 3:12 | The entire exposition repeats itself | |

| 6:21 | Transition played by flute, oboe and bassoon followed by third theme in strings;

Music. |

DEVELOPMENT SECTION:

Transition to third theme |

| 6:40 | Modulations in this section add to the instability of the section; Starts like the exposition but with repetition in different keys. | Modulation to the minor |

| 7:21 | Slight introduction of third theme motif;

Quiet and subdued. |

Implied recapitulation: “Transition” |

| 8:05 | Now started by the oboes and bassoons;

Now in C minor, not E flat major, which provides a more ominous tone. |

Recapitulation in original key: First theme |

| 9:29 | Pause followed by second theme | |

| 10:39 | After a sudden piano articulation of the SSSL motive, suddenly ends in a loud and bombastic manner: Fate threatens;

Re-emphasizes C minor. |

Third theme |

| 10:53 | Closing material similar to exposition | |

| 11:09 | Full orchestra at forte dynamic. | Closing cadence for the movement |

It is impossible to know how many more operas and symphonies Mozart would have written had he lived into his forties, fifties, or even sixties. Haydn’s music written after the death of Mozart shows the influence of his younger contemporary, and Beethoven’s early music was also shaped by Mozart’s. In fact, in 1792, a twenty-something Beethoven was sent to Vienna with the expressed purpose of receiving “the spirit of Mozart from the hands of Haydn.”

5.7 MUSIC OF LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Beethoven was born in Bonn in December of 1770. As you can see from the map at the beginning of this chapter, Bonn sat at the Western edge of the Germanic lands, on the Rhine River. Those in Bonn were well-acquainted with traditions of the Netherlands and of the French; they would be some of the first to hear of the revolutionary ideas coming out of France in the 1780s. The area was ruled by the Elector of Cologne. As the Kapellmeister for the Elector, Beethoven’s grandfather held the most important musical position in Bonn, but he died when Beethoven was three years old. Ludwig’s father, Johann, sang in the Electoral Chapel his entire life. While he may have provided his son with his early music lessons, Johann suffered from alcoholism and depression, especially after the death of Maria Magdalena Keverich (Johann’s wife and Ludwig’s mother) in 1787.

The close ties between Vienna and Cologne made it convenient for the Elector, with the support of the music-loving Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein (1762-1823), to send Ludwig to Vienna to further his music training. The Count was the youngest of an aristocratic family in Bonn, and he greatly supported the arts and became a patron of Beethoven. Beethoven’s first stay in Vienna in 1787 was interrupted by the death of his mother. In 1792, he returned to Vienna for good.

Perhaps the most universally known fact about Beethoven is that he became deaf. You can read entire books on the topic; for our present purposes, the timing of his hearing loss is most important. At the end of the 1790s, Beethoven first recognized he was losing his hearing. By 1801, he was writing about it to his most trusted friends. The loss of his hearing was clearly an existential crisis for Beethoven. During the fall of 1802, he composed a letter to his brothers that included his last will and testament, a document that we’ve come to know as the “Heiligenstadt Testament” named after the small town of Heiligenstadt, north of the Viennese city center, where he was staying. (Testament) The “Heiligenstadt Testament” provides us insight into Beethoven’s heart and mind. Most striking is his statement that his experiences of social alienation, connected to his hearing loss, “drove me almost to despair, a little more of that and I have ended my life—it was only my art that held me back.” The idea that Beethoven found in art a reason to live suggests both his valuing of art and a certain self-awareness of what he had to offer music. Beethoven and his physicians tried various means to counter hearing loss and improve his ability to function in society. By 1818, however, Beethoven was completely deaf. He was 48 years old.

Beethoven had a complex personality. Although he read the most profound philosophers of his day and was compelled by lofty philosophical ideals, his own writing was flawed, and his personal accounts show errors in basic math. He craved close human relationships yet had difficulty sustaining them. By 1810, he had secured a lifetime annuity from local noblemen, meaning that Beethoven never lacked for money. Still, his letters—as well as the accounts of contemporaries—suggest a man suspicious of others and preoccupied with the compensation he was receiving.

5.7.1 Overview of Beethoven’s Music

Upon arriving in Vienna in the early 1790s, Beethoven supported himself by playing piano at salons and by giving music lessons. Salons were gatherings of literary types, visual artists, musicians, and thinkers, often hosted by noblewomen for their friends. Beethoven performed his own compositions and improvised on musical themes given to him by those attending.

In April of 1800 Beethoven gave his first concert for his own benefit, held at the important Burgtheater. As typical for the time, the concert included a variety of types of music, vocal, orchestral, and even, in this case, chamber music. Many of the selections were by Haydn and Mozart, for Beethoven’s music from this period was profoundly influenced by these two composers.

Scholars have traditionally divided Beethoven’s composing into three chronological periods: early, middle, and late. Like all efforts to categorize, this one proposes boundaries that are open to debate. Probably the most controversial is the dating of the end of the middle period and the beginning of the late period. Beethoven did not compose much music between 1814 and 1818, meaning that any division of those years would fall more on Beethoven’s life than on his music.

In general, the music of Beethoven’s first period (roughly until 1803) reflects the influence of Haydn and Mozart. Beethoven’s second period (1803-1814) is sometimes called his “heroic” period, based on his recovery from depression documented in the “Heiligenstadt Testament” mentioned earlier. This period includes such music compositions as his Third Symphony, which Beethoven subtitled “Eroica” (that is, heroic), the Fifth Symphony, and Beethoven’s one opera, Fidelio, which took the French revolution as its inspiration. Other works composed during this time include Symphonies No. 3 through No. 8 and famous piano works, such as the sonatas “Waldstein,” “Appassionata,” and “Lebewohl” and Concertos No. 4 and No. 5. He continued to write instrumental chamber music, choral music, and songs into his heroic middle period. In these works of his middle period, Beethoven is often regarded as having come into his own because they display a new and original musical style. In comparison to the works of Haydn and Mozart and Beethoven’s earlier music, these longer compositions feature larger performing forces, thicker textures, more complex motivic relationships, more dissonance, more syncopation and hemiola (hemiola is the simultaneous sense of being in two meters at the same time), and more elaborate forms.

When Beethoven started composing again in 1818 (after the hearing loss*), his music was much more experimental. Some of his contemporaries believed he lost his ability to compose as he lost his hearing. The late piano sonatas, last five string quartets, monumental Missa Solemnis, and Symphony No. 9 in D minor (The Choral Symphony) are now perceived to be some of Beethoven’s most revolutionary compositions, although they were not uniformly applauded during his lifetime. Beethoven’s late style was one of contrasts: extremely slow music next to extremely fast music and extremely complex and dissonant music next to extremely simple and consonant music.

*While the hearing loss was a personal blow to his health, it was not a musical end. Think about the song, “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” How does it start? Can you “hear” that in your head? Musicians develop a finely tuned sense of the music in what we call the “inner voice” – the music in your head. Beethoven, as Mozart before him, simply needed to write down what he heard in that inner voice.

Although this chapter will not discuss the music of Beethoven’s early period or late period in any depth, you might want to explore this music on your own. Beethoven’s first published piano sonata, the Sonata in F minor, Op. 2, No. 1 (1795), shows the influence of Haydn, to whom he dedicated it. One of Beethoven’s last works, his famous Ninth Symphony, departs from the norms of the day by incorporating vocal soloists and a choir into a symphony, which was almost always written only for orchestral instruments. The Ninth Symphony is Beethoven’s longest; its first three movements, although innovative in many ways, use the expected forms: a fast sonata form, a scherzo (which by the early nineteenth century—as we will see in our discussion of the Fifth Symphony—had replaced the standard minuet and trio for a third movement), and a slow theme and variations form. The finale, in which the vocalists participate, is truly revolutionary in terms of its length, the sheer extremes of the musical styles it uses, and the combination of large orchestra and choir. The text or words that Beethoven chose for the vocalists speak of joy and the hope that all humankind might live together in brotherly love. The “Ode to Joy” melody to which Beethoven set these words was later used for the hymn “Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee.”

Focus Composition: Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 (1808)

In this chapter, we will focus on possibly Beethoven’s most famous composition, his Fifth Symphony (1808). The premier of the Fifth Symphony took place at perhaps the most infamous of all of Beethoven’s concerts, an event that lasted for some four hours in an unheated theater on a bitterly cold Viennese evening. At this time, Beethoven was not on good terms with the performers, several who refused to rehearse with the composer in the room. In addition, the final number of the performance was finished too late to be sufficiently practiced, and in the concert, it had to be stopped and restarted. Belying its less than auspicious first performance, once published the Fifth Symphony quickly gained the critical acclaim it has held ever since.

What follows is a guide to help you focus on specific features in all four movements of this, perhaps the most famous symphony of all time. For the best experience, you may wish to read through the next few pages (all about this symphony), and then start here again to follow these notes with each movement as you listen to the audio. Allow yourself uninterrupted time to read and apply these notes to the music. The entire symphony takes approximately 30 minutes to perform.

The most famous part of the Fifth Symphony is its commanding opening in this first movement. In unison, the orchestra plays a motive called the short-short-short-long (SSSL) motive, named for the rhythm of its four notes. We will also refer to it as the Fate motive, because at least since the 1830s, music critics have likened it to fate knocking on the door. The short notes repeat the same pitch and then the long note leaps down a third. After the orchestra releases the held note, it plays the motive again, now sequenced a step lower, then again at the original pitches, then at higher pitches. This sequenced phrase, which has become the first theme of the movement, then repeats, and the fast sonata-form movement starts to pick up steam. This occurs in the exposition (the first third) of this movement.

After a transition (a bridge that connects and moves to a new key), the second theme is heard. It also starts with the SSSL motive, although the pitches heard are quite different. The horn presents the question phrase of the second theme; then, the strings respond with the answer phrase of the second theme. You should note that the key has changed—the music is now in E flat major, which has a much more peaceful feel than C minor—and the answer phrase of the second theme is much more legato than anything yet heard in the symphony. This tuneful legato music does not last for long and the closing section returns to the rapid sequencing of the SSSL motive. Then the orchestra returns to the beginning of the movement for a repeat of the exposition.

The development section of this first movement does everything we might expect of a development: the SSSL motive appears in sequence and is altered as the keys change rapidly. Near the end of the development, the dynamics alternate between piano and forte and, before the listener knows it, the music has returned to the home key of C minor as well as the opening version of the SSSL motive: this begins the third section of this first movement – the recapitulation. Then, just when the listener expects the recapitulation to end, Beethoven extends the movement in a coda (Italian for “tail”). This coda is much longer than any coda in the music of Haydn or Mozart, although it is not as long as the coda to the final movement of this symphony. These long codas are also another element that Beethoven is known for. He often restates the conclusion many times and in many rhythmic durations.

The second movement is a lyrical theme and variations movement in a major key, which provides a few minutes of respite from the menacing C minor; if you listen carefully, though, you might hear some reference to the SSSL fate motive.

The third movement returns to C minor and is a scherzo. Scherzos retain the form of the minuet, having a contrasting trio section that divides the two presentations of the scherzo. Scherzos also have a triple feel, although they tend to be somewhat faster in tempo than the minuet. This movement opens with a mysterious, even spooky, opening theme played by the lower strings. The second theme returns to the SSSL motive, although now with different pitches. The mood changes with a very imitative and very polyphonic trio in C major, but the spooky theme reappears, alongside the fate motive, with the repeat of the scherzo. Instead of making the scherzo an independent movement as are the first and second movements, Beethoven chose to write a musical transition between the scherzo and the final movement, so that the music runs continuously from one movement to another. After suddenly getting very soft, the music gradually grows in dynamic as the motive sequences higher and higher until the fourth movement bursts onto the scene with a triumphant and loud C major theme. It seems that perhaps our hero, whether we think of the hero as the music of the symphony or perhaps as Beethoven himself, has finally triumphed over Fate.

The fourth movement is a typical fast finale in sonata form. The movement ultimately ends with loud cadences in C major, providing ample support for an interpretation of the composition as the overcoming of Fate. This is the interpretation that most commentators have given the symphony. Listen to the piece and see if you hear it the same way.

LISTENING GUIDE

For audio of the first and second movements performed by the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique (on period instruments) conducted by John Eliot Gardiner:

For audio of the third and fourth movements performed by the Simon Bolivar Orchestra in 2017, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel:

- Composer: Beethoven

- Composition: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

- Date: 1808

- Genre: symphony

- Form: Four movements as follows:

Allegro con brio – fast, sonata form

Andante con moto – slow, theme and variations form

Scherzo. Allegro – Scherzo and Trio (ABA)

Allegro – fast, sonata form

- Performing Forces: piccolo (fourth movement only), two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon (fourth movement only), two horns, two trumpets, three trombones (fourth movement only), timpani, and strings (first and second violins, viola, cellos, and double basses)

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- Its fast first movement in sonata form opens with the short-short-short-long motive (which pervades much of the symphony): Fate knocking at the door?

- The symphony starts in C minor but ends in C major: a triumphant over fate?

Allegro con brio (movt 1)

If you truly want to understand music a bit better, check out this wonderfully done, 10-minute guided analysis by Gerard Schwarz of the first movement: ven-part-1

What we want you to remember about this movement

- Its fast first movement in sonata form opens with the short-short-short-long motive (which pervades much of the symphony): Fate knocking at the door?

- Its C minor key modulates for a while to other keys but returns at the end of this movement

- The staccato first theme comprised of sequencing of the short-short-short-long motive (SSSL) greatly contrasts the more lyrical and legato second theme

- The coda at the end of the movement provides dramatic closure.

Table 3: Listening Guide for Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | Full orchestra in a mostly homophonic texture and forte dynamic. Melody starts with the SSSL motive introduced and then suspended with a fermata (or hold). After this happens twice, the melody continues with the SSSL motive in rising sequences. | EXPOSITION: First theme |

| 0:21 | The forte dynamic continues, with emphasis from the timpani.

Falling sequences using the SSSL rhythm. |

Transition |

| 0:40 | After the horn call, the strings lead this quieter section.

A horn call using the SSSL motive introduces a more lyrical theme— now in a major key. |

Second theme |

| 1:01 | SSSL rhythms passes through the full orchestra that plays at a forte dynamic.

The SSSL rhythm returns in down- ward sequences. |

Closing |

| 1:17 | EXPOSITION: Repeats | |

| 2:32 | Some polyphonic imitation; lots of dialogue between the low and high instruments and the strings and winds.

Rapid sequences and changing of keys, fragmentation and alternation of the original motive. |

DEVELOPMENT |

| 3:23 | Music moves from louds to softs | Retransition |

| 3:40 | but ends with a short oboe cadenza. Starts like the exposition. | RECAPITULATION: First theme |

| 4:09 | Similar to the transition in the exposition but does not modulate. | “Transition” |

| 4:28 | Now started by the oboes and bassoons.

Now in C minor, not E flat major, which provides a more ominous tone. |

Second theme |

| 4:53 | As above | Closing |

| 5:08 | After a sudden piano articulation of the SSSL motive, suddenly ends in a loud and bombastic manner: Fate threatens.

Re-emphasizes C minor. |

Coda |

Allegro con moto (mvt. 2)

A guided analysis by Gerard Schwarz of the second movement.

What we want you to remember about this movement:

- It is a slow theme and variations movement

- Its major key provides contrast from the minor key of the first movement

Table 4: Listening Guide for Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 0:00 [6:32] | Mostly homophonic.

Consists of two themes, the first more lyrical; the second more march-like. |

Theme: a and b |

| 1:40 [8:12] | More legato and softer at the beginning, although growing loud for the final statement of b in the brass before decrescendoing to piano again. Violas subdivide the beat with fast running notes, while the other instruments play the theme. | Variation 1: a and b |

| 3:15 [9:47] | Starts with a softer dynamic and more legato articulations for the “a” phrase and staccato and louder march-like texture when “b” enters, after which the music decrescendos into the next variation.

Even more rapid subdivision of the beat in the lower strings at the beginning of “a.” Then the “b” phrase returns at the very end of the section. |

Variation 2: a and b |

| 5:30 [12:02] | Lighter in texture and more staccato, starting piano and crescendoing to forte for the final variation.

The “a” phrase assumes a jaunty rhythm and then falls apart . |

Variation 3: a |

| 6:05 [12:37] | The full orchestra plays forte and then sections of the orchestra trade motives at a quieter dynamic.

The violins play the first phrase of the melody and then the winds respond with its answer. |

Variation 4: A |

| 6:46 [13:17] | Full orchestra plays, soft at first, and then crescendoing, decrescendoing, and crescendoing a final time to the end of the movement.

Motives are passed through the orchestra and re-emphasized at the very end of the movement. |

Coda |

Scherzo. Allegro (mvt 3)

What we really want you to remember about this movement:

- It is a scherzo movement that has a scherzo (A) trio (B) scherzo (A) form

- The short-short-short-long motive returns in the scherzo sections

- The scherzo section is mostly homophonic, and the trio section is mostly imitative polyphony

- It flows directly into the final movement without a break

Table 5: Listening Guide for Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|---|---|---|

| 15:26 | Lower strings and at a quiet dynamics. Rapidly ascending legato melody. | Scherzo (A): A |

| 15:49 | Presented by the brass in a forte dynamic.

Fate motive. |

B |

| 16:05 | a b a b | |

| 17:09 | Polyphonic imitation lead by the lower strings.

Fast melody. |

Trio (B): c c d d |

| 18:30 | Now the repetitious SSSL theme is played by the bassoons, staccato. Fast melody. | Scherzo (A): A |

| 18:49 | Strings are playing pizzicato (plucking) and the whole ensemble playing at a piano dynamic.

Fate motive but in the oboes and strings. |

B |

| 19:31 | Very soft dynamic to begin with and then slowly crescendos to the forte opening of the fourth movement.

Sequenced motive gradually as- cends in register. |

Transition to the fourth movement |

Allegro (mvt. 4)

What we want you to remember about this movement:

- It is a fast sonata form movement in C major: the triumph over Fate?

- The SSSL motive via the scherzo “b” theme returns one final time at the end of the development

- The trombones for their first appearance in a symphony to date

- It has a very long coda

Table 6: Listening Guide for Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

| 20:02 [0:31] | Forte and played by the full orchestra (including trombones, contrabassoon and piccolo).

Triumph triadic theme in C major. |

EXPOSITION: First theme |

|---|---|---|

| 20:41 | Full orchestra, led by the brass and then continued by the strings.

The opening motive of the first theme sequenced as the music modulates to the away key. |

Transition |

| 21:05 [1:31] | Full orchestra and slightly softer. Triumphant, if more lyrical, using triplet rhythms in the melody and in G Major. | Second theme |

| 21:34 [2:11] | Full orchestra, forte again. Repetition of a descending them. | Closing theme |

| 22:03 [2:29] | Motives passed through all sections of the orchestra.

Motives from second theme appear, then motives from the first theme. |

DEVELOPMENT |

| 23:36 [4:00] | Piano dynamic with the theme in the winds and the strings accompanying. Using the fate motive | Return of scherzo theme |

| 24:11 [4:35] | Performing forces are as before. C major. | RECAPITULATION: First

theme |

| 24:43 [5:08] | Performing forces are as before. Does not modulate. | “transition” |

| 25:14 [5:39] | As before. | Second theme |

| 25:39 [6:04] | Starts softly with the woodwinds and then played forte by the whole orchestra.

Does not modulate. |

Closing theme |

| 26:11 [6:40] | Notice the dramatic silences, the alternation of of legato and staccato articulations, and the sudden increase in tempo near the coda’s conclusion: full orchestra.

Lengthy coda starting with motive from second theme, then proceeding through with a lot of repeated cadences emphasizing C major and repetition of other motives until the final repeated cadences. |

CODA |

5.8 CHAPTER SUMMARY

As we have seen, the approximate 75 years that span the musical compositions of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven were rife with innovations in musical genre, style, and form. In many ways, they shaped music for the next 200 years. Composers continued to write symphonies and string quartets, using forms such as the sonata, theme, and variations. A large portion of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century society continued playing music in the home and going to theaters for opera and to concerts at which orchestral compositions such as concertos and symphonies were performed. Although that live performance culture may not be as prevalent at the beginning of the twenty-first century, we might ask why it was so important for Western music culture for so long. We also might ask if any of its elements inform our music of today.

5.9 GLOSSARY

Cadenza – section of a concerto in which the soloist plays alone without the orchestra in an improvisatory style

Chamber music – music—such as art songs, piano character pieces, and string quartets— primarily performed in small performing spaces, often for personal entertainment

Coda – optional final section of a movement that reasserts the home key of the movement and provides a sense of conclusion

Da capo– instruction—commonly found at the end of the B section or Trio of a Minuet and Trio, to return to the “head” or first section, generally resulting in an A B A form

Development – the middle section of a sonata-form movement in which the themes and key areas introduced in the exposition are developed;

Double-exposition form – form of the first movement of a Classical period concerto that combines the exposition, development, and recapitulation of sonata form with the ritornello form used for the first movements of Baroque concertos; also called first-movement concerto form

Exposition – first section of a sonata form movement, in which the themes and key areas of the movement are introduced; the section normally modulates from the home key to a different key

Hemiola – the momentary shifting from a duple to a triple feel or vice versa

Minuet and trio form – form based on the minuet dance that consists of a Minuet (A), then a contrasting Trio (B), followed by a return to the Minuet (A)

Opera Buffa – comic style of opera made famous by Mozart

Opera Seria – serious style of eighteenth-century opera made famous by Handel generally features mythology or high-born characters and plots

Pizzicato – the plucking of a bowed string instrument such as the violin, producing a percussive effect

Recapitulation – third and final second of a sonata-form movement, in which the themes of the exposition return, now in the home key of the movement

Rondo – instrumental form consisting of the alternation of a refrain “A” with contrasting sections (“B,” “C,” “D,” etc.). Rondos are often the final movements of string quartets, classical symphonies, concerti, and sonata (instrumental solos).

Scherzo – form that prominently replaced the minuet in symphonies and strings quartets of the nineteenth century; like the minuet, scherzos are ternary forms and have a triple feel, although they tend to be somewhat faster in tempo than the minuet.

Sonata form– a form often found in the first and last movements of sonatas, symphonies, and string quartets, consisting of three parts—exposition, development, and recapitulation

String quartet – performing ensemble consisting of two violinists, one violinist, and one cellist that plays compositions called string quartets, compositions generally in four movements

Symphony – multi-movement composition for orchestra, often in four movements

Ternary form – describes a musical composition in three parts, most often featuring two similar sections, separated by a contrasting section and represented by the letters A – B – A.

Theme and Variation form – the presentation of a theme and then variations upon it. The theme may be illustrated as A, with any number of variations following it – A’, A’’, A’’’, A’’’’, etc.

[1] Crowest, “An Estimate of Mozart,”The Eclectic Magazine: Foreign Literature Vol. 55; Vol 118 P. 464

multi-movement composition for orchestra, often in four movements

performing ensemble consisting of two violinists, one violinist, and one cellist that plays compositions called string quartets, compositions generally in four movements

a form often found in the first and last movements of sonatas, symphonies, and string quartets, consisting of three parts—exposition, development, and recapitulation

instrumental form consisting of the alternation of a refrain “A” with contrasting sections (“B,” “C,” “D,” etc.). Rondos are often the final movements of string quartets, classical symphonies, concerti, and sonata (instrumental solos).

music—such as art songs, piano character pieces, and string quartets— primarily performed in small performing spaces, often for personal entertainment

comic style of opera made famous by Mozart

first section of a sonata form movement, in which the themes and key areas of the movement are introduced; the section normally modulates from the home key to a different key

the middle section of a sonata-form movement in which the themes and key areas introduced in the exposition are developed;

third and final second of a sonata-form movement, in which the themes of the exposition return, now in the home key of the movement

the momentary shifting from a duple to a triple feel or vice versa

form that prominently replaced the minuet in symphonies and strings quartets of the nineteenth century; like the minuet, scherzos are ternary forms and have a triple feel, although they tend to be somewhat faster in tempo than the minuet.

optional final section of a movement that reasserts the home key of the movement and provides a sense of conclusion

section of a concerto in which the soloist plays alone without the orchestra in an improvisatory style

the plucking of a bowed string instrument such as the violin, producing a percussive effect