1 Public Speaking Today

Learning Objectives

- Explore the types of public speaking.

- Understand the benefits of public speaking.

- Understand the basic principles of public speaking.

- Explain the nature and types of communication apprehension.

- Identify effective techniques for coping with speech anxiety during speech preparation and delivery.

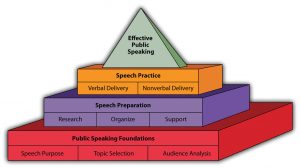

Public speaking is the process of designing and delivering a message to a public audience. Effective public speaking involves understanding your audience and speaking goals, choosing elements for the speech that will engage your audience with your topic, and delivering your message skillfully. Effective public speakers understand that they must plan, organize, and revise their material before speaking. This book will help you understand the basics of effective public speaking and guide you through the process of creating your own presentations. We will begin by discussing how public speaking is relevant to you and can benefit you in your career, education, and personal life. Then, we will introduce some of the basic principles of public speaking.

In a world where television, social media, and the Internet bombard people with messages, one of the first questions you may ask is, “Do people still give speeches?” Well, type the words “public speaking” into Amazon.com or Barnesandnoble.com, and you will find more than two thousand books with the words “public speaking” in the title. Most of these and other books related to public speaking are not college textbooks. In fact, many books written about public speaking are intended for specific audiences: A Handbook of Public Speaking for Scientists and Engineers (by Peter Kenny), Excuse Me! Let Me Speak!: A Young Person’s Guide to Public Speaking (by Michelle J. Dyett-Welcome), Professionally Speaking: Public Speaking for Health Professionals (by Frank De Piano and Arnold Melnick), and Speaking Effectively: A Guide for Air Force Speakers (by John A. Kline). Although these different books address specific issues related to nurses, engineers, or air force officers, the content is similar.

If you search for “public speaking” in an online academic database, you’ll find numerous articles on public speaking in business magazines (e.g., BusinessWeek, Nonprofit World) and academic journals (e.g., Harvard Business Review, Journal of Business Communication). There is so much information available about public speaking because it continues to be relevant even with the growth of technological means of communication. Author and speaker Scott Berkun writes in his blog, “For all our tech, we’re still very fond of the most low tech thing there is: a monologue” (Berkun, 2009). People continue to spend millions of dollars every year to listen to professional speakers. For example, attendees of the 2010 TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) conference, which invites speakers from around the world to share their ideas in short, eighteen-minute presentations, paid six thousand dollars per person to listen to fifty speeches over a four-day period.

Technology can also help public speakers reach audiences that were not possible to connect with in the past. Millions of people heard about and then watched Randy Pausch’s “Last Lecture” online. In this captivating speech, Randy Pausch, a Carnegie Mellon University professor who retired at age forty-six after developing inoperable tumors, delivered his last lecture to the students, faculty, and staff. Friends turned this inspiring speech into a DVD and a best-selling book that was eventually published in more than thirty-five languages (Carnegie Mellon University, 2011).

We realize that you may not be invited to TED to give the speech of your life or create a speech so inspirational that it touches the lives of millions via YouTube; however, all of us will find ourselves in situations where we will be asked to give a speech, make a presentation, or just deliver a few words. In this chapter, we will first address why public speaking is essential, and then we will discuss models that illustrate the process of public speaking itself.

Why is Public Speaking Important?

In this book, we are beginning with the assumption that public speaking matters. It matters to our world, personal lives, and professional lives. Public speaking is not merely about conveying information, but it can be a powerful tool for change. In what follows we will introduce some of the basic principles and benefits of public speaking.

Roots of Public Speaking

The ancient Greeks were some of the earliest people to write about public speaking because they viewed speech as critical to a democracy. The Greeks began studying rhetoric in the 5th century BCE when adult male citizens had a duty to participate in government and the courts (Kennedy 1991, p. vii). Rhetoric can be defined as the study and practice of communication that can persuade audiences. Some Greek philosophers were deeply skeptical about rhetoric because they recognized its power to be used for both good and evil. However, other scholars, such as Aristotle, insisted that rhetoric is morally neutral. If people are mindful of ethics, rhetoric can be a powerful tool for both social good and individual benefit. The Greeks considered speech to be part of what creates and maintains a public. Public speaking was not an abstract concept. Instead, it was a vital tool for daily life and necessary to sustain a democracy.

The Public

A public is a community of people with shared concerns. Sometimes we think about a public in terms of nation or community (people of the United States of America or Milwaukee), but we can also think about publics as being organized around shared interests or identities (fans of Dr. Who, students, or people who support drug legalization). Furthermore, we always belong to multiple publics at the same time. You might have even noticed you belong to more than one of the publics that were mentioned. Through speech, speakers can create, shape, and influence publics. We will return to the concept of a public in the chapter about audience, but it is important to recognize that part of the reason public speaking is valuable is a result of its relationship to a public.

Common Types of Public Speaking

Every single day people, across the United States and around the world, stand up in front of some kind of audience and speak. In fact, there’s even a monthly publication that reproduces some of the top speeches from around the United States called Vital Speeches of the Day. Although public speeches are of various types, they can generally be grouped into three categories: informative, persuasive, and ceremonial/entertaining.

Informative Speaking

One of the most common types of public speaking is informative speaking. The primary purpose of informative speeches is to share one’s knowledge of a subject with an audience. Reasons for making an informative speech vary widely. For example, you might be asked to instruct a group of coworkers on how to use new computer software or to report to a group of managers how your latest project is coming along. A local community group might wish to hear about your volunteer activities in New Orleans during spring break or learn about the different approaches to reduce homelessness in your community. What all these examples have in common, is the goal of imparting information to an audience.

Informative speaking is integrated into many different occupations. Physicians often lecture about their areas of expertise to medical students, other physicians, and patients. Teachers find themselves presenting to parents as well as to their students. Firefighters give demonstrations about how to effectively control a fire in the house. Informative speaking is a common part of numerous jobs and other everyday activities. As a result, learning how to speak effectively has become an essential skill in today’s world.

Persuasive Speaking

A second common reason for speaking to an audience is to persuade others. In our everyday lives, we are often called on to convince, motivate, or otherwise persuade others to change their beliefs, take an action, or reconsider a decision. Advocating for music education in your local school district, convincing clients to purchase your company’s products, or inspiring high school students to attend college all involve influencing other people through public speaking.

For some people, such as elected officials, giving persuasive speeches is a crucial part of attaining and continuing career success. Other people make careers out of speaking to groups of people who pay to listen to them. Motivational authors and speakers, such as Les Brown, make millions of dollars each year from people who want to be motivated to do better in their lives. Brian Tracy, another professional speaker, and author, specializes in helping business leaders become more productive and effective in the workplace.

Whether public speaking is something you do every day or just a few times a year, persuading others is a challenging task. If you develop the skill to persuade effectively, it can be personally and professionally rewarding.

Ceremonial Speaking

Ceremonial speaking involves an array of speaking occasions ranging from introductions to wedding toasts, to presenting and accepting awards, to delivering eulogies at funerals and memorial services in addition to after-dinner speeches and motivational speeches. Entertaining speaking has been important since the time of the ancient Greeks when Aristotle identified epideictic speaking (speaking in a ceremonial context) as an important type of address. As with persuasive and informative speaking, there are professionals, from religious leaders to comedians, who make a living simply from delivering entertaining speeches. As anyone who has watched an awards show on television or has seen an incoherent best man deliver a wedding toast can attest, speaking to entertain is a task that requires preparation and practice to be effective.

Benefits of Public Speaking

Once you’ve learned the basic skills associated with public speaking, you’ll find that being able to effectively speak in public has profound benefits, including:

- influencing the world around you,

- developing leadership skills,

- becoming a thought leader.

Influencing the World around You

If you don’t like something about your local government, then speak out about your issue! One of the best ways to get our society to change is through the power of speech. Common citizens in the United States and around the world, like you, are influencing the world in real ways through the power of speech. Just type the words “citizens speak out” in a search engine and you’ll find numerous examples of how common citizens use the power of speech to make real changes in the world. There are speeches where citizens are speaking out against “fracking” for natural gas (a process in which chemicals are injected into rocks in an attempt to open them up for fast flow of natural gas or oil) or in favor of retaining a popular local sheriff. One of the amazing parts of being a citizen in a democracy is the right to stand up and speak out, which is a luxury many people in the world do not have. So if you don’t like something, be the force of change you’re looking for through the power of speech.

Developing Leadership Skills

Have you ever thought about climbing the corporate ladder and eventually finding yourself in a management or other leadership position? If so, then public speaking skills are very important. Hackman and Johnson assert that effective public speaking skills are necessary for all leaders (Hackman & Johnson, 2004). If you want people to follow you, you have to clearly and effectively communicate your expectations. According to Bender, “Powerful leadership comes from knowing what matters to you. Powerful presentations come from expressing this effectively. It’s important to develop both” (Bender, 1998). One of the most important skills for leaders to develop is their public speaking skills, which is why executives spend millions of dollars every year going to public speaking workshops and hiring public speaking coaches.

Becoming a Thought Leader

Even if you are not in an official leadership position, effective public speaking can help you become a “thought leader.” Editor of Strategy & Business, Joel Kurtzman, coined this term to call attention to individuals who contribute new ideas to the world of business. Typically, thought leaders engage in a range of behaviors, including enacting and conducting research on business practices. To achieve thought leader status, individuals must communicate their ideas to others through both writing and public speaking. Lizotte demonstrates how becoming a thought leader can be personally and financially rewarding at the same time: when others look to you as a thought leader, you will be more desired and make more money as a result. Business gurus often refer to “intellectual capital,” or the combination of your knowledge and ability to communicate that knowledge to others (Lizotte, 2008). Whether standing before a group of executives discussing the next great trend in business or delivering a webinar (a seminar over the web), thought leaders create the world we live in by using public speaking.

Public Speaking Skills

Oral communication skills were ranked number one by college graduates when asked which skills they found useful in the business world, according to a study by sociologist Andrew Zekeri (Zekeri, 2004). That fact alone makes learning about public speaking worthwhile. However, there are many other benefits of communicating effectively with the hundreds of thousands of college students every year who take public speaking courses. Let’s take a look at some of the personal benefits you’ll get both from a course in public speaking and from giving public speeches.

In addition to learning the process of creating and delivering an effective speech, public speaking students leave the class with a number of other benefits as well. Some of these benefits include:

- developing critical thinking skills,

- fine-tuning verbal and nonverbal skills,

- overcoming the fear of public speaking.

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

One of the very first benefits you will gain from your public speaking course is an increased ability to think critically. Problem solving is one of the many critical thinking skills you will engage in during this course. For example, when preparing a persuasive speech, you’ll have to think through real problems affecting your campus, community, or the world and provide possible solutions to those problems. You’ll also have to consider the positive and negative consequences of your solutions and then communicate your ideas to others. At first, it may seem easy to come up with solutions for a campus problem such as a shortage of parking spaces: just build more spaces. But after thinking and researching further you may find out that building costs, environmental impact from the loss of green space, maintenance needs, or limited locations for additional spaces make this solution impractical. Being able to think through problems and analyze the potential costs and benefits of solutions is an essential part of critical thinking and of public speaking aimed at persuading others. These skills will help you not only in public speaking contexts but throughout your life as well. As we stated earlier, college graduates in Zekeri’s study rated oral communication skills as the most useful for success in the business world. The second most valuable skill they reported was problem-solving. So, your public speaking course is doubly valuable!

Fine-Tuning Verbal and Nonverbal Skills

A second benefit of taking a public speaking course is that it will help you fine-tune your verbal and nonverbal communication skills. Whether you competed in public speaking competitions in high school or this is your first time speaking in front of an audience, having the opportunity to actively practice communication skills and receive professional feedback will help you become a better overall communicator. Often, people don’t even realize that they twirl their hair or repeatedly mispronounce words while speaking in public settings until they receive feedback from a teacher during a public speaking course. People around the United States will often pay speech coaches over one hundred dollars per hour to help them enhance their speaking skills. You have a built-in speech coach right in your classroom, so it is to your advantage to use the opportunity to improve your verbal and nonverbal communication skills.

Overcoming Fear of Public Speaking

An additional benefit of taking a public speaking class is that it will help reduce your fear of public speaking. Whether you’ve spoken in public a lot or are just getting started, most people experience some anxiety when engaging in public speaking. Heidi Rose and Andrew Rancer evaluated students’ levels of public speaking anxiety during both the first and last weeks of their public speaking class. They found student’s levels of anxiety decreased over the course of the semester (Rose & Rancer, 1993). One explanation is that by taking a course in public speaking, students become better acquainted with the public speaking process, making them more confident and less apprehensive. In addition, you will learn specific strategies for overcoming the challenges of speech anxiety

Public: A community with shared concerns or interests.

Rhetoric: The study and practice of communication that can persuade audiences.

What Is Communication Apprehension?

Speaker at Podium – CC BY 2.0.

“Speech is a mirror of the soul,” commented Publilius Syrus, a popular writer in 42 BCE (Bartlett, 1919). Other people come to know who we are through our words. Many different social situations, ranging from job interviews to dating to public speaking, can make us feel uncomfortable as we anticipate that we will be evaluated and judged by others. How well we communicate is intimately connected to our self-image. The process of revealing ourselves to the evaluation of others can be threatening whether we are meeting new acquaintances, participating in group discussions, or speaking in front of an audience.

One of your most significant concerns about public speaking might be how to deal with nervousness or unexpected events. If that’s the case, you’re not alone. Fear of speaking in public consistently ranks at the top of lists of people’s common worries. Some people are not joking when they say they would rather die than stand up and speak in front of a live audience. The fear of public speaking ranks right up there with the fear of flying, death, and spiders (Wallechinsky, Wallace, & Wallace, 1977). Even if you are one of the fortunate few who doesn’t typically get nervous when speaking in public, it’s important to recognize things that can go wrong and be mentally prepared for them. On occasion, people misplace speaking notes, have technical difficulties with a presentation aid, or get distracted by an audience member. Confidently speaking involves knowing how to deal with these and other unexpected events while speaking.

In this chapter, we will help you gain the knowledge to speak confidently by exploring what communication apprehension is, examining the different types and causes of communication apprehension, suggesting strategies you can use to manage your fears of public speaking, and providing tactics you can use to deal with a variety of unexpected events you might encounter while speaking.

Definition of Communication Apprehension

According to James McCroskey, communication apprehension refers to an individual’s “fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (McCroskey, 2001). At its heart, communication apprehension is a psychological response to being evaluated. This psychological response quickly becomes physical as our body responds to the threat the mind perceives. Our bodies cannot distinguish between psychological and physical threats, so we react as though we were facing a truck barreling in our direction. The body’s circulatory and adrenal systems shift into overdrive, preparing us to function at maximum physical efficiency—the “flight or fight” response (Sapolsky, 2004). Instead of running away or fighting, all we need to do is stand and talk. When it comes to communication apprehension, our physical responses are often not well adapted to the nature of the threat we face, as the excess energy created by our body can make it harder for us to be competent public speakers. But because communication apprehension is rooted in our minds, if we understand more about the nature of the body’s responses to stress, we can better develop mechanisms for managing the body’s misguided attempts to help us cope with our fear of social judgment.

Communication Apprehension is the fear or anxiety people experience at the thought of communicating with others or in the act of communicating with others.

Physiological Symptoms of Communication Apprehension

Isaac Mao – Brain – CC BY 2.0.

There are many physical sensations associated with communication apprehension. We might notice our heart pounding or our hands feeling clammy. We may break out in a sweat. We may have “stomach butterflies” or even feel nauseated. Our hands and legs might start to shake, or we may begin to nervously pace. Our voices may quiver, and we may have a “dry mouth” sensation that makes it difficult to articulate even simple words. Our breathing may become more rapid and, in extreme cases, we might feel dizzy or light-headed. Anxiety about communicating is profoundly disconcerting because we feel powerless to control our bodies. Furthermore, we may become so anxious that we fear we will forget our name, much less remember the main points of the speech we are about to deliver.

The physiological changes produced in the body at critical moments are designed to contribute to the efficient use of muscles and expand available energy. Circulation and breathing become more rapid so that additional oxygen can reach the muscles. Increased circulation causes us to sweat. Adrenaline rushes through our body, instructing the body to speed up its movements. If we stay immobile behind a lectern, this hormonal urge to speed up may produce shaking and trembling. Additionally, digestive processes are inhibited so we will not lapse into the relaxed, sleepy state that is typical after eating. Instead of feeling sleepy, we feel butterflies in the pit of our stomach. By understanding what is happening to our bodies in response to the stress of public speaking, we can better cope with these reactions and channel them in constructive directions.

Any conscious emotional state such as anxiety or excitement consists of two components: a primary reaction of the central nervous system and an intellectual interpretation of these physiological responses. The physiological state we label as communication anxiety does not differ from ones we label rage or excitement. Even experienced, compelling speakers and performers experience some communication apprehension. What differs is the mental label that we put on the experience. Effective speakers have learned to channel their body’s reactions, using the energy released by these physiological reactions to create animation and stage presence.

Myths about Communication Apprehension

A wealth of conventional wisdom surrounds the discomfort of speaking anxiety, as it surrounds almost any phenomenon that makes us uncomfortable. Most of this “folk” knowledge misleads us, directing our attention away from effective strategies for thinking about and coping with anxiety reactions. Before we look in more detail at the types of communication apprehension, let’s dispel some of the myths about it.

- People who suffer from speaking anxiety are neurotic. As we have explained, speaking anxiety is a typical reaction. Good speakers can get nervous just as poor speakers do. Winston Churchill, for example, would get physically ill before significant speeches in Parliament. Yet, he rallied the British people in a time of crisis. Many people, even the most professional performers, experience anxiety about communicating. It is such a widespread problem, Dr. Joyce Brothers contends, “cannot be attributed to deep-seated neuroses” (Brothers, 2008).

- Telling a joke or two is always a good way to begin a speech. Humor is some of the toughest material to effectively deliver because it requires an exquisite sense of timing. Nothing is worse than waiting for a laugh that does not come. Moreover, one person’s joke is another person’s slander. It is extremely easy to offend when using humor. The same material can play very differently with different audiences. For these reasons, it is not a good idea to start with a joke, particularly if it is not well related to your topic. Humor is just too unpredictable and difficult for many novice speakers. If you insist on using humor, make sure the “joke” is on you, not on someone else. Another tip is never to pause and wait for a laugh that may not come. If the audience catches the joke, fine. If not, you’re not left standing in awkward silence waiting for a reaction.

- Imagine the audience is naked. This tip just plain doesn’t work because imagining the audience naked will do nothing to calm your nerves. As Malcolm Kushner noted, “There are some folks in the audience I wouldn’t want to see naked—especially if I’m trying not to be frightened” (Kushner, 1999). The audience is not some abstract image in your mind. It consists of real individuals who you can connect with through your material. To “imagine” the audience is to misdirect your focus from the real people in front of you to an “imagined” group. What we imagine is usually more threatening than the reality that we face.

- Any mistake means that you have “blown it.” We all make mistakes. What matters is not whether we make a mistake but how well we recover. One of the authors of this book was giving a speech and wanted to thank a former student in the audience. Instead of saying “former student,” she said, “former friend.” After the audience stopped laughing, the speaker remarked, “Well, I guess she’ll be a former friend now!” This impromptu statement got even more laughter from the audience. A speech does not have to be perfect. You just need to make an effort to relate to the audience naturally and be willing to accept your mistakes.

- Avoid speaking anxiety by writing your speech out word for word and memorizing it. Memorizing your speech word for word will likely make your apprehension worse rather than better. Instead of remembering three to five main points and subpoints, you will try to commit to memory more than a thousand bits of data. If you forget a point, the only way to get back on track is to start from the beginning. You are inviting your mind to go blank by overloading it with details. In addition, audiences do not like to listen to “canned,” or memorized, material. Your delivery is likely to suffer if you memorize. Audiences appreciate speakers who talk naturally to them rather than recite a written script.

- Audiences are out to get you. With only a few exceptions, which we will talk about, the natural state of audiences is empathy, not antipathy. Most face-to-face audiences are interested in your material, not in your image. Watching someone who is anxious tends to make audience members anxious themselves. Particularly in public speaking classes, audiences want to see you succeed. They know that they will soon be in your shoes and they identify with you, most likely hoping you’ll succeed and give them ideas for how to make their own speeches better. If you establish direct eye contact with real individuals in your audience, you will see them respond to what you are saying, and this response lets you know that you are succeeding.

- You will look to the audience as nervous as you feel. Empirical research has shown that audiences do not perceive the level of nervousness that speakers report feeling (Clevenger, 1959). Most listeners judge speakers as less anxious than speakers rate themselves. In other words, the audience is not likely to perceive accurately the level of anxiety you might be experiencing. Some of the most effective speakers will return to their seats after their speech and exclaim they were so nervous. Listeners will respond, “You didn’t look nervous.” Audiences do not necessarily perceive our fears. Consequently, don’t apologize for your nerves. There is a good chance the audience will not notice if you do not point it out to them.

- A little nervousness helps you give a better speech. This “myth” is true! Professional speakers, actors, and other performers consistently rely on the heightened arousal of nervousness to channel extra energy into their performance. People would much rather listen to a speaker who is alert and enthusiastic than one who is relaxed to the point of boredom. Many professional speakers say that the day they stop feeling nervous is the day they should stop speaking in public. The goal is to control those nerves and channel them into your presentation.

All Anxiety Is Not the Same: Sources of Communication Apprehension

We have said that experiencing some form of anxiety is a common part of the communication process. Most people are anxious about being evaluated by an audience. Interestingly, many people assume that their nervousness is an experience unique to them. They believe that other people do not feel anxious when confronting the threat of public speaking (McCroskey, 2001). Although anxiety is a widely shared response to the stress of public speaking, not all anxiety is the same. Many researchers have investigated the differences between apprehension grounded in personality characteristics and anxiety prompted by a particular situation at a specific time (Witt, et al., 2006). McCroskey argues there are four types of communication apprehension: anxiety related to traits, context, audience, and situation (McCroskey, 2001). If you understand these different types of apprehension, you can gain insight into the varied communication factors that contribute to speaking anxiety.

Trait Anxiety

Some people are just more disposed to communication apprehension than others. As Witt, Brown, Roberts, Weisel, Sawyer, and Behnke explain, “Trait anxiety measures how people generally feel across situations and time periods” (Witt, et al., 2006). Some people feel more uncomfortable than the average person regardless of the context, audience, or situation. It doesn’t matter whether you are raising your hand in a group discussion, talking with people you meet at a party, or giving speeches in a class, you’re likely to be uncomfortable in all these settings if you experience trait anxiety. While trait anxiety is not the same as shyness, those with high trait anxiety are more likely to avoid exposure to public speaking situations. This avoidance means their nervousness might be compounded by their lack of experience or skill (Witt, et. al., 2006). People who experience trait anxiety may never like public speaking, but through preparation and practice, they can learn to give effective public speeches when they need to do so.

Context Anxiety

MTEA – Michelle Alexander at Podium – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Context anxiety refers to anxiety prompted by specific communication contexts. Some of the significant context factors that can heighten this form of anxiety are formality, uncertainty, and novelty.

Formality

Some individuals can be entirely composed when talking at a meeting or in a small group; yet when faced with a more formal public speaking setting, they become intimidated and nervous. As the formality of the communication context increases, the stakes are raised, sometimes prompting more apprehension. Certain communication contexts, such as a press conference or a courtroom, can make even the most confident individuals nervous. One reason is that these communication contexts presuppose an adversarial relationship between the speaker and some audience members.

Uncertainty

It is hard to predict and control the flow of information in such contexts, so the level of uncertainty is high. The feelings of context anxiety might be similar to those you experience on the first day of class with a new instructor. You don’t know what to expect, so you are more nervous than you might be later in the semester when you know more about the instructor.

Novelty

Many of us are not experienced in high-tension communication settings. The novelty of the communication context we encounter is another factor contributing to apprehension. Anxiety becomes more of an issue in communication environments that are new to us, even for those who are ordinarily comfortable with speaking in public.

Most people can learn through practice to cope with their anxiety prompted by formal, uncertain, and novel communication contexts. Fortunately, most public speaking classroom contexts are not adversarial. The opportunities you have to practice giving speeches reduces the novelty and uncertainty of the public speaking context, enabling most students to learn how to cope with anxiety prompted by the communication context.

Audience Anxiety

For some individuals, it is not the communication context that prompts anxiety; it is the people in the audience they face. Audience anxiety describes communication apprehension prompted by specific audience characteristics. These characteristics include similarity, subordinate status, audience size, and familiarity.

You might not have difficulty talking to an audience of your peers in student government meetings, but an audience composed of students and parents on a campus visit might make you nervous. The degree of perceived similarity between you and your audience can influence your level of speech anxiety. We all prefer to talk to an audience that we believe shares our values more than to one that does not. The more dissimilar we are from our audience members, the more likely we are to be nervous. Studies have shown that subordinate status can also contribute to speaking anxiety (Witt, et. al., 2006). Talking in front of your boss or teacher may be intimidating, especially if they are evaluating you. The size of the audience can also play a role. The larger the audience, the more threatening the situation may seem. Finally, familiarity can be a factor. Some of us prefer talking to strangers rather than to people we know well. Others feel more nervous in front of an audience of friends and family because there is more pressure to perform well.

Situational Anxiety

Situational anxiety, McCroskey explains, is the communication apprehension created by “the unique combination of influences generated by audience, time and context” (McCroskey, 2001). Each communication event involves several dimensions: physical, temporal, social-psychological, and cultural. These dimensions combine to create a unique communication situation that is different from any previous communication event. The situation created by a given audience, in a given time, and in a given context can coalesce into situational anxiety.

Reducing Communication Apprehension

Freddie Pena – Nervous? – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Experiencing some nervousness about public speaking is normal. The energy created by this physiological response can be functional if you harness it as a resource for more effective public speaking. In this section, we suggest steps that you can take to channel your stage fright into excitement and animation. We will begin with specific speech-related considerations and then briefly examine some of the more general anxiety management options available.

Speech-related Considerations

Communication apprehension does not necessarily remain constant throughout all the stages of speech preparation and delivery. One group of researchers studied the ebb and flow of anxiety levels during the four stages of delivery in a speech. They compared indicators of physiological stress at different milestones in the process:

- anticipation (the minute prior to starting the speech),

- confrontation (the first minute of the speech),

- adaptation (the last minute of the speech), and

- release (the minute immediately following the end of the speech) (Witt, et al., 2006).

These researchers found that anxiety typically peaked at the anticipatory stage. In other words, we are likely to be most anxious right before we get up to speak. As we progress through our speech, our level of anxiety is likely to decline. Planning your speech to incorporate techniques for managing your nervousness at different times will help you decrease the overall level of stress you experience. We also offer some suggestions for managing your reactions while you are delivering your speech.

Think Positively

As we mentioned earlier, communication apprehension begins in the mind as a psychological response. This natural response underscores the importance of a speaker’s psychological attitude toward speaking. To prepare yourself mentally for a successful speaking experience, we recommend using a technique called cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring involves changing how you label the physiological responses you will experience. Rather than thinking of public speaking as a dreaded obligation, make a conscious decision to consider it an exciting opportunity. The first audience member that you have to convince is yourself, by deliberately replacing negative thoughts with positive ones. If you say something to yourself often enough, you will gradually come to believe it.

We also suggest practicing what communication scholars Metcalfe, Beebe, and Beebe call positive self-talk rather than negative self-talk (Metcalfe, 1994; Beebe, 2000). If you find yourself thinking, “I’m going to forget everything when I get to the front of the room,” stop and turn that negative message around to a positive one. Tell yourself, “I have notes to remind me what comes next, and the audience won’t know if I don’t cover everything in the order I planned.” The idea is to dispute your negative thoughts and replace them with positive ones, even if you think you are “conning” yourself. By monitoring how you talk about yourself, you can unlearn old patterns and change the ways you think about things that produce anxiety.

Reducing Anxiety through Preparation

As we have said earlier in this chapter, uncertainty makes for greater anxiety. Nothing is more frightening than facing the unknown. Although no one can see into the future and predict everything that will happen during a speech, every speaker can prepare to keep the “unknowns” of the speech event to a minimum. You can do this by gaining as much knowledge as possible about whom you will be addressing, what you will say, how you will say it, and where the speech will take place.

Analyze Your Audience

The audience that we imagine in our minds is almost always more threatening than the reality of the people sitting in front of us. The more information you have about the characteristics of your audience, the more compelling message you can craft for your audience. Since your stage fright is likely to be at its highest at the beginning of your speech, it is helpful to open the speech with a technique to prompt an audience response. You might try posing a question, asking for a show of hands, or sharing a story that you know is relevant to your listeners’ experience. When you see the audience responding to you by nodding, smiling, or answering questions, you will have directed the focus of attention from yourself to the audience. Such responses indicate success; they are positively reinforcing, and thus reduce your nervousness.

Clearly Organize Your Ideas

Being prepared as a speaker means knowing the main points of your message so well that you can remember them even when you are feeling highly anxious. The best way to learn those points is to create an outline for your speech. With a clear outline to follow, you will find it much easier to move from one point to the next without stumbling or getting lost.

A note of caution is in order: you do not want to react to the stress of speaking by writing and memorizing a manuscript. Your audience will usually be able to tell that you wrote your speech out verbatim, and they will tune out very quickly. You are setting yourself up for disaster if you try to memorize a written text because the pressure of having to remember all those particulars will be tremendous. Moreover, if you have a momentary memory lapse during a memorized speech, you may have a lot of trouble continuing without starting over at the beginning.

What you do want to prepare is a simple outline that reminds you of the progression of ideas in your speech. What is important is the order of your points, not the specifics of each sentence. It is perfectly fine if your speech varies in terms of specific language or examples each time you practice it.

It may be a good idea to reinforce this organization through visual aids. When it comes to managing anxiety, visual aids have the added benefit of taking attention off the speaker.

Adapt Your Language to the Oral Mode

Another reason not to write out your speech as a manuscript is that to speak effectively, you want to adapt your language to the oral, not the written, mode. You will find your speaking anxiety more manageable if you speak in the oral mode because it will help you to feel like you are having a conversation with friends rather than delivering a formal proclamation.

An appropriate oral style is more concrete and vivid than written style. Effective speaking relies on verbs rather than nouns, and the language is less complicated. Long sentences may work well for novelists such as William Faulkner or James Joyce, where readers can go back and reread passages two, three, or even seven or eight times. Your listeners, though, cannot “rewind” you to catch ideas they miss the first time through.

Don’t be afraid to use personal pronouns freely, frequently saying “I” and “me”—or better yet, “us” and “we.” Personal pronouns are much more effective in speaking than language constructions, such as the following “this author,” because they help you to build a connection with your audience. Another oral technique is to build audience questions into your speech. Rhetorical questions, questions that do not require a verbal answer, invite the audience to participate with your material by thinking about the implications of the question and how it might be answered. If you are graphic and concrete in your language selection, your audience is more likely to listen attentively. You will be able to see the audience listening, and this feedback will help to reduce your anxiety.

Practice in Conditions Similar to Those You Will Face When Speaking

It is not enough to practice your speech silently in your head. To reduce anxiety and increase the likelihood of a successful performance, you need to practice out loud in a situation similar to the one you will face when actually performing your speech. Practice delivering your speech out loud while standing on your feet. If you make a mistake, do not stop to correct it but continue all the way through your speech because that is what you will have to do when you are in front of the audience.

If possible, practice in the actual room where you will be giving your speech. Not only will you have a better sense of what it will feel like to speak, but you may also have the chance to practice using presentation aids. Practicing in the room allows you to potentially avoid distractions and glitches like incompatible computers, blown projector bulbs, or sunlight glaring in your eyes.

Two handy tools for anxiety-reducing practice are a clock and a mirror. Use the clock to time your speech, being aware that most novice speakers speak too fast, not too slow. By ensuring that you are within the time guidelines, you will eliminate the embarrassment of having to cut your remarks short because you’ve run out of time or of not having enough to say to fulfill the assignment. Use the mirror to gauge how well you are maintaining eye contact with your audience. It will allow you to check that you are looking up from your notes. It will also help you build the habit of using appropriate facial expressions to convey the emotions in your speech. While you might feel a little absurd practicing your speech out loud in front of a mirror, the practice that you do before your speech can make you much less anxious when it comes time to face the audience.

Watch What You Eat

A final tip about preparation is to watch what you eat immediately before speaking. The butterflies in your stomach are likely to be more noticeable if you skip meals. While you should eat normally, you should avoid caffeinated drinks because they can make your shaking hands worse. Carbohydrates operate as natural sedatives, so you may want to eat carbohydrates to help slow down your metabolism and to avoid fried or very spicy foods that may upset your stomach. If you are speaking in the morning, be sure to have breakfast. If you haven’t had anything to eat or drink since dinner the night before, dizziness and light-headedness are genuine possibilities.

Reducing Nervousness during Delivery

Anticipate the Reactions of Your Body

There are steps you can take to counteract the adverse physiological effects of stress on the body. Deep breathing will help to offset the effects of excess adrenaline. You can place symbols in your notes, like “slow down” or ☺, that remind you to pause and breathe during points in your speech. It is also a good idea to pause a moment before you get started to set an appropriate pace from the onset. Look at your audience and smile. It is a reflex for some of your audience members to smile back. Those smiles will reassure you that your audience members are friendly.

Physical movement helps to channel some of the excess energy that your body produces in response to anxiety. If at all possible, move around the front of the room rather than remaining imprisoned behind the podium or gripping it for dear life. If you walk from behind the podium, avoid pacing nervously from side to side. Move closer to the audience and then stop for a moment. If you are afraid that moving away from the podium will reveal your shaking hands, use note cards rather than a sheet of paper for your outline. Note cards do not quiver like paper, and they provide you with something to do with your hands.

Vocal warm-ups are also important before speaking. Just as athletes warm up before practice or competition and musicians warm up before playing, speakers need to get their voices ready to speak. Talking with others before your speech or quietly humming to yourself can get your voice ready for your presentation. You can even sing or practice a bit of your speech out loud while you’re in the shower, where the warm, moist air is beneficial for your vocal mechanism. Gently yawning a few times is also an excellent way to stretch the key muscle groups involved in speaking.

Immediately before you speak, you can relax the muscles of your neck and shoulders, rolling your head gently from side to side. Allow your arms to hang down by your sides and stretch out your shoulders. Isometric exercises that involve momentarily tensing and then relaxing specific muscle groups are an effective way to keep your muscles from becoming stiff.

Focus on the Audience, Not on Yourself

During your speech, make a point of establishing direct eye contact with your audience members. By looking at individuals, you develop a series of one-to-one connections similar to interpersonal communication. An audience becomes much less threatening when you think of them not as an anonymous mass but as a collection of individuals.

A colleague once shared his worst public speaking experience. When he reached the front of the room, he forgot everything he was supposed to say. When I asked what he saw when he was in the front of the room, he looked at me like I was crazy. He responded, “I didn’t see anything. All I remember is a mental image of me up there in the front of the room blowing it.” Speaking anxiety becomes more intense if you focus on yourself rather than concentrating on your audience and your material.

Maintain Your Sense of Humor

No matter how well we plan, unexpected things happen. That fact is what makes the public speaking situation so interesting. When the unexpected happens to you, do not let it rattle you. At the end of a class period after a long day, a student raised her hand and asked me if I knew that I was wearing two different colored shoes. I looked down and saw that she was right. One of my shoes was black and one was blue. I laughed at myself, complimented the student on her observational abilities, and moved on with the important thing, the material I had to deliver.

Stress Management Techniques

Even when we employ positive thinking and are well prepared, some of us still feel a great deal of anxiety about public speaking. When that is the case, it can be more helpful to use stress management than to try to make the tension go away.

One general technique for managing stress is positive visualization. Visualization is the process of seeing something in your mind’s eye; essentially, it is a form of self-hypnosis. Frequently used in sports training, positive visualization involves using the imagination to create images of relaxation or ultimate success. You imagine in great detail the goal for which you are striving, like a rousing round of applause after you give your speech. You mentally picture yourself standing at the front of the room, delivering your introduction, moving through the body of your speech, highlighting your presentation aids, and sharing a memorable conclusion. If you imagine a positive outcome, your body will respond to it as though it were real. Such mind-body techniques create the psychological grounds for us to achieve the goals we have imagined. As we discussed earlier, communication apprehension has a psychological basis, so mind-body techniques such as visualization can be essential for reducing anxiety. It’s important to keep in mind, though, that visualization does not mean you can skip practicing your speech out loud. Just as an athlete still needs to work out and practice the sport, you need to practice your speech to achieve the positive results you visualize.

Systematic desensitization is a behavioral modification technique that helps individuals overcome anxiety disorders. People with phobias, or irrational fears, tend to avoid the object of their fear. For example, people with a phobia of elevators avoid riding in elevators—and this only adds to their fear because they never “learn” that riding in elevators is usually perfectly safe. Systematic desensitization changes this avoidance pattern by gradually exposing the individual to the object of fear until it can be tolerated.

First, the individual is trained in specific muscle relaxation techniques. Next, the individual learns to respond with conscious relaxation even when confronted with the situation that previously caused them fear. James McCroskey used this technique to treat students who suffered from severe, trait-based communication apprehension (McCroskey, 1972). He found that “the technique was eighty to ninety percent effective” for the people who received the training (McCroskey, 2001). If you’re highly anxious about public speaking, you might begin a program of systematic desensitization by watching someone else give a speech. Once you can do this without discomfort, you would then move to talking about giving a speech yourself, practicing, and, eventually, delivering your speech.

The success of techniques such as these indicates that increased exposure to public speaking reduces overall anxiety. Consequently, you should seek out opportunities to speak in public rather than avoid them. As the famous political orator William Jennings Bryan once noted, “The ability to speak effectively is an acquirement rather than a gift” (Carnegie, 1955).

Coping with the Unexpected

Des Morris – I H8 PC – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Even the most prepared, confident public speaker may encounter unexpected challenges during the speech. This section discusses some everyday unexpected events and addresses some general strategies for combating the unexpected when you encounter it in your speaking.

Speech Content Issues

Nearly every experienced speaker has gotten to the middle of a presentation and realized that a key notecard is missing or that they skipped important information from the beginning of the speech. When encountering these difficulties, a good strategy is to pause for a moment to think through what you want to do next. Is it essential to include the missing information, or can it be omitted without hurting the audience’s ability to understand the rest of your speech? If it needs to be included, do you want to add the information now, or will it fit better later in the speech? It is often difficult to remain silent when you encounter this situation, but pausing for a few seconds will help you to figure out what to do and may be less distracting to the audience than sputtering through a few “ums” and “uhs.”

Technical Difficulties

Technology has become a beneficial aid in public speaking, allowing us to use audio or video clips, presentation software, or direct links to websites. However, one of the best-known truisms about technology is that it does break down. Web servers go offline, files will not download in a timely manner, and media are incompatible with the computer in the presentation room. It is necessary to always have a backup plan, developed in advance, in case of technical difficulties with your presentation materials. As you create your speech and visual aids, think through what you will do if you cannot show a particular graph or if your presentation slides are hopelessly garbled. Although your beautifully prepared chart may be superior to the verbal description you can provide, your ability to provide a succinct oral description when technology fails can give your audience the information they need.

External Distractions

Although many public speaking instructors directly address audience etiquette during speeches, you’re still likely to encounter an audience member who walks in late, a ringing cell phone, or even a car alarm going off outside your classroom. If you are distracted by external events like these, it is often useful, and sometimes necessary, to pause and wait so that you can regain the audience’s attention.

Whatever the unexpected event, your most important job as a speaker, is to maintain your composure. It is important not to get upset or angry because of these types of glitches. The key is to be fully prepared. If you keep your cool and quickly implement a “plan B” for moving forward with your speech, your audience is likely to be impressed and may listen even more attentively to the rest of your presentation.

References

Arnett, R. C., & Arneson, P. (1999). Dialogic civility in a cynical age: Community, hope, and interpersonal relationships. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Bakhtin, M. (2001a). The problem of speech genres. (V. W. McGee, Trans., 1986). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1227–1245). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953.).

Bakhtin, M. (2001b). Marxism and the philosophy of language. (L. Matejka & I. R. Titunik, Trans., 1973). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1210–1226). Boston, MA: Medford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953).

Barnlund, D. C. (2008). A transactional model of communication. In C. D. Mortensen (Ed.), Communication theory (2nd ed., pp. 47–57). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Bartlett, J. (comp.). (1919). Familiar quotations (10th ed.). Rev. and enl. by Nathan Haskell Dole. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company. Retrieved from Bartleby.com website: http://www.bartleby.com/100.

Beebe, S.A., & Beebe, S. J. (2000). Public speaking: An audience centered approach. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Bender, P. U. (1998). Stand, deliver and lead. Ivey Business Journal, 62(3), 46–47.

Berkun, S. (2009, March 4). Does public speaking matter in 2009? [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://www.scottberkun.com/blog.

Carnegie, D. (1955). Public speaking and influencing men in business. New York, NY: American Book Stratford Press, Inc.

Carnegie Mellon University. (n.d.). Randy Pausch’s last lecture. Retrieved June 6, 2011, from http://www.cmu.edu/randyslecture.

Clevenger, T. J. (1959). A synthesis of experimental research in stage fright. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 45, 135–159. See also Savitsky, K., & Gilovich, T. (2003). The illusion of transparency and the alleviation of speech anxiety. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 601–625.

DeVito, J. A. (2009). The interpersonal communication book (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Edmund, N. W. (2005). End the biggest educational and intellectual blunder in history: A $100,000 challenge to our top educational leaders. Ft. Lauderdale, FL: Scientific Method Publishing Co.

Geissner, H., & Slembek, E. (1986). Miteinander sprechen und handeln [Speak and act: Living and working together]. Frankfurt, Germany: Scriptor.

Hackman, M. Z., & Johnson, C. E. (2004). Leadership: A communication perspective (4th ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland.

Lizotte, K. (2008). The expert’s edge: Become the go-to authority people turn to every time [Kindle 2 version]. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Retrieved from Amazon.com (locations 72–78).

Kushner, M. (1999). Public speaking for dummies. New York, NY: IDG Books Worldwide, p. 242.

McCroskey, J. C. (2001). An introduction to rhetorical communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 40.

McCroskey, J. C. (1972). The implementation of a large-scale program of systematic desensitization for communication apprehension. The Speech Teacher, 21, 255–264.

Metcalfe, S. (1994). Building a speech. New York, NY: The Harcourt Press.

Mortenson, C. D. (1972). Communication: The study of human communication. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Rose, H. M., & Rancer, A. S. (1993). The impact of basic courses in oral interpretation and public speaking on communication apprehension. Communication Reports, 6, 54–60.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of communication (pp. 3–26). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Wallechinsky, D., Wallace, I., & Wallace, A. (1977). The people’s almanac presents the book of lists. New York, NY: Morrow.

West, R., & Turner, L. H. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, p. 13.

Witt, P. L., Brown, K. C., Roberts, J. B., Weisel, J., Sawyer, C., & Behnke, R. (2006, March). Somatic anxiety patterns before, during and after giving a public speech. Southern Communication Journal, 71, 87–100.

Wrench, J. S., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2008). Human communication in everyday life: Explanations and applications. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 17.

Yakubinsky, L. P. (1997). On dialogic speech. (M. Eskin, Trans.). PMLA, 112(2), 249–256. (Original work published in 1923).

Zekeri, A. A. (2004). College curriculum competencies and skills former students found essential to their careers. College Student Journal, 38, 412–422.

See also Boyd, J. H., Rae, D. S., Thompson, J. W., Burns, B. J., Bourdon, K., Locke, B. Z., & Regier, D. A. (1990). Phobia: Prevalence and risk factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 25(6), 314–323.