1.1 Overview of Individual Tax Formula

Learning Objectives

- Identify and define the core components of the individual tax formula.

- Explain the sequential flow and interrelationships within the tax formula.

- Apply the formula to calculate taxable income in a basic scenario.

Module Overview

Calculating an individual’s income tax liability in the United States involves a step-by-step process built upon foundational concepts. The calculation begins with the determination of gross income, which encompasses all income from various sources such as wages, salaries, tips, interest, and dividends (Internal Revenue Code [I.R.C.] § 61). From this initial figure, certain adjustments to income are subtracted to arrive at adjusted gross income (AGI) (I.R.C. § 62). Taxpayers then further reduce their AGI to determine taxable income by either claiming the standard deduction, an amount that varies based on filing status, or by itemizing deductions for eligible expenses like medical costs, state and local taxes (subject to limitations), and home mortgage interest (I.R.C. §§ 63, 161-224). Once taxable income is established, the relevant tax rates, which are often progressive with higher incomes taxed at higher rates, are applied to compute the initial tax liability (I.R.C. § 1). Finally, this liability is reduced by any applicable tax credits, and prepayments made throughout the year (e.g., through payroll withholding) are subtracted to determine the final tax owed or the amount to be refunded (Internal Revenue Service [IRS], Publication 17).

These steps not only establish a taxpayer’s liability but also reflect the broader goals of the tax code, such as encouraging certain activities, providing relief, and promoting fairness. To better understand how these concepts function in practice, we will examine the key components of tax calculation: income, deductions, and credits and individual income tax formula.

- Income: The Starting Point of Tax Calculation. Income is the foundation of taxation. It represents the inflow of economic value taxpayers receive from various sources. This includes earned income like wages, salaries, tips, and self-employment income; investment income such as dividends, interest, and capital gains; and other forms of income like rents, royalties, and retirement distributions. It’s crucial to understand that not all income is treated the same under the tax law; different types of income may be taxed at different rates or have specific rules associated with them. Not all income is treated the same under tax law. Some income may be taxed at different rates, receive preferential treatment, or follow special rules.

- Deductions: Reducing the Taxable Base. Deductions are essentially expenses that the tax law allows taxpayer to subtract from total income to arrive at taxable income. Taxable income is the amount of income that is actually subject to taxation. Deductions come in various forms, broadly categorized as “above-the-line” (adjustments to gross income) and “below-the-line” (itemized or standard deductions and Qualified Business Deduction). Deductions reduce taxable income, but their availability often depends on specific qualifications and limitations.

- Credits: Direct Tax Savings. Tax credits are even more significant than deductions because they directly reduce the tax liability on a dollar-for-dollar basis. Congress often uses credits to encourage certain behaviors or provide relief to targeted groups of taxpayers. For example, education credits promote investment in higher education, while child-related credits provide support for families. Like deductions, credits come in different forms and are subject to eligibility requirements and limitations.

Tax forms are standardized documents that taxpayers use to report income, deductions, and credits, ultimately applying the tax formula to calculate their liability to the IRS. At the end of the day, it is important to understand how the different sections of the main tax form and supporting schedules work together to ensure accurate reporting and compliance with tax laws.

The Individual Tax Formula

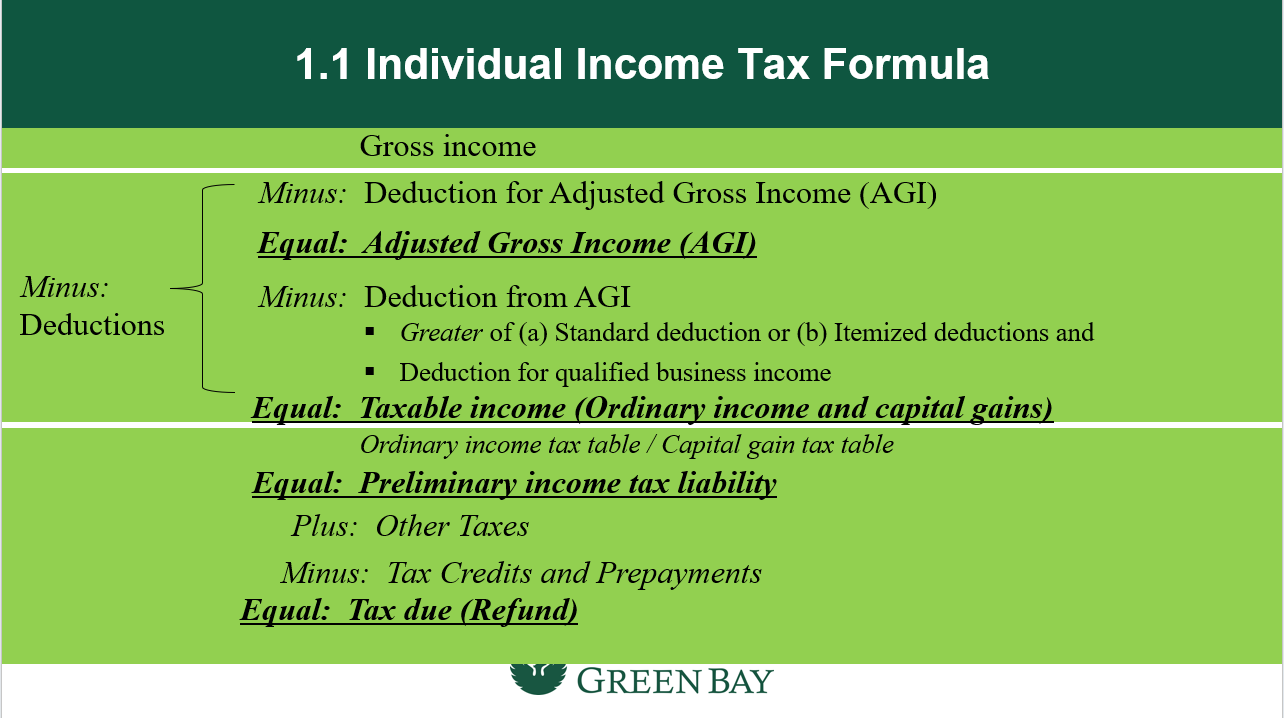

The U.S. individual income tax system is organized around a formula that determines the amount of tax a taxpayer must pay or whether a refund will be received. This formula is the foundation of individual taxation and provides a logical sequence that connects income, deductions, credits, and payments into a unified process. Understanding this structure helps explain how different tax provisions interact to influence the final outcome.

The process begins with gross income, which is defined broadly as all income received during the year unless specifically excluded by law. Wages, salaries, business income, interest, dividends, and rental income are common examples. Congress deliberately designed gross income to capture the widest possible measure of a taxpayer’s economic activity before allowing exclusions and adjustments.

From gross income, certain “above-the-line” adjustments are subtracted to arrive at adjusted gross income (AGI). Adjustments include contributions to retirement accounts, student loan interest, and health savings account contributions, among others. AGI is more than just an intermediate step: it serves as a key benchmark because eligibility for many deductions and credits is determined by AGI. In short, AGI affects both the size of taxable income and access to other tax benefits.

Once AGI has been calculated, the taxpayer determines taxable income. This amount is found by subtracting either the standard deduction or itemized deductions, such as mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and charitable contributions, from AGI. Additional deductions, such as the qualified business income deduction, may also apply. The resulting figure, taxable income, is the base on which the federal income tax rates are applied. The United States uses a progressive tax system, meaning that lower portions of income are taxed at lower rates, while higher portions are taxed at higher rates.

Applying the tax rates to taxable income produces the tentative tax liability. This is the amount of tax owed before considering credits or prepayments. At this stage, the calculation reflects only income and deductions.

The next step incorporates tax credits and prepayments. Credits, such as the Child Tax Credit or education credits, reduce tax liability dollar for dollar and are therefore often more valuable than deductions. Prepayments, including withholding from wages and estimated tax payments, are also applied. Taken together, these amounts directly offset the tentative tax liability.

Finally, the taxpayer compares total tax liability with credits and prepayments to determine the final tax due or refund. If liability exceeds credits and prepayments, additional tax is owed. If credits and prepayments exceed liability, the taxpayer receives a refund. This step completes the formula and represents the ultimate financial obligation to the federal government.

Form 1040 and Supporting Forms/Schedules

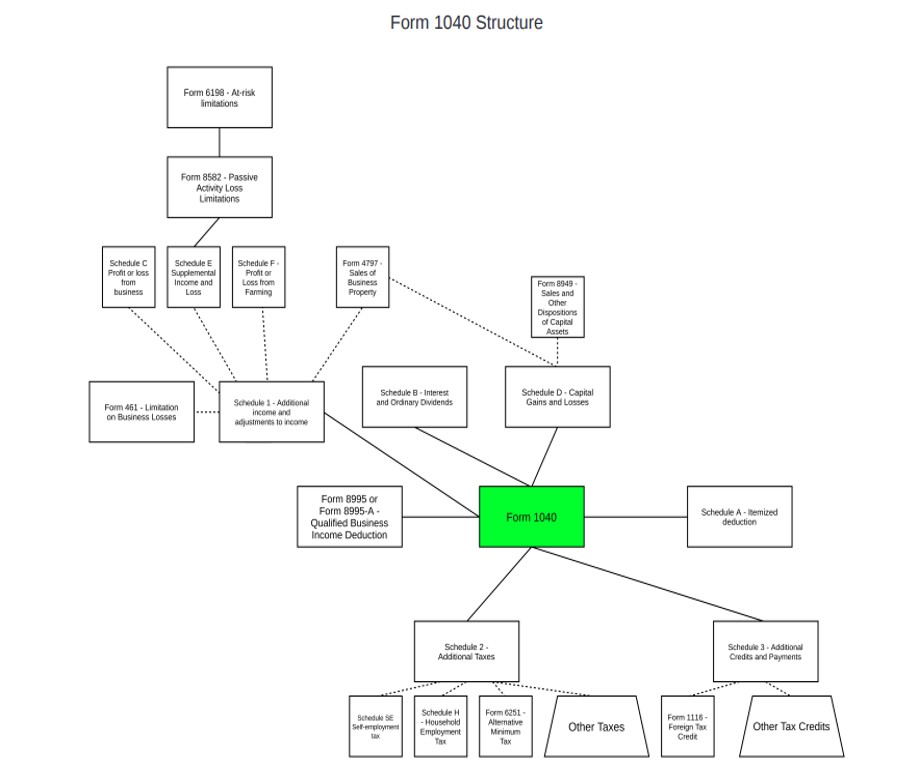

Tax forms are the standardized documents used to report taxpayer’s income, deductions, credits, and ultimately calculate the tax liability to the IRS. Form 1040, U.S. Individual Income Tax Return is the primary form used in individual federal income tax filing. It is supported by various schedules and forms that provide detailed information about specific types of income, deductions, and credits. For example, Schedule C reports business income, Schedule D reports capital gains and losses, and Schedule 1 captures additional types of income and adjustments.

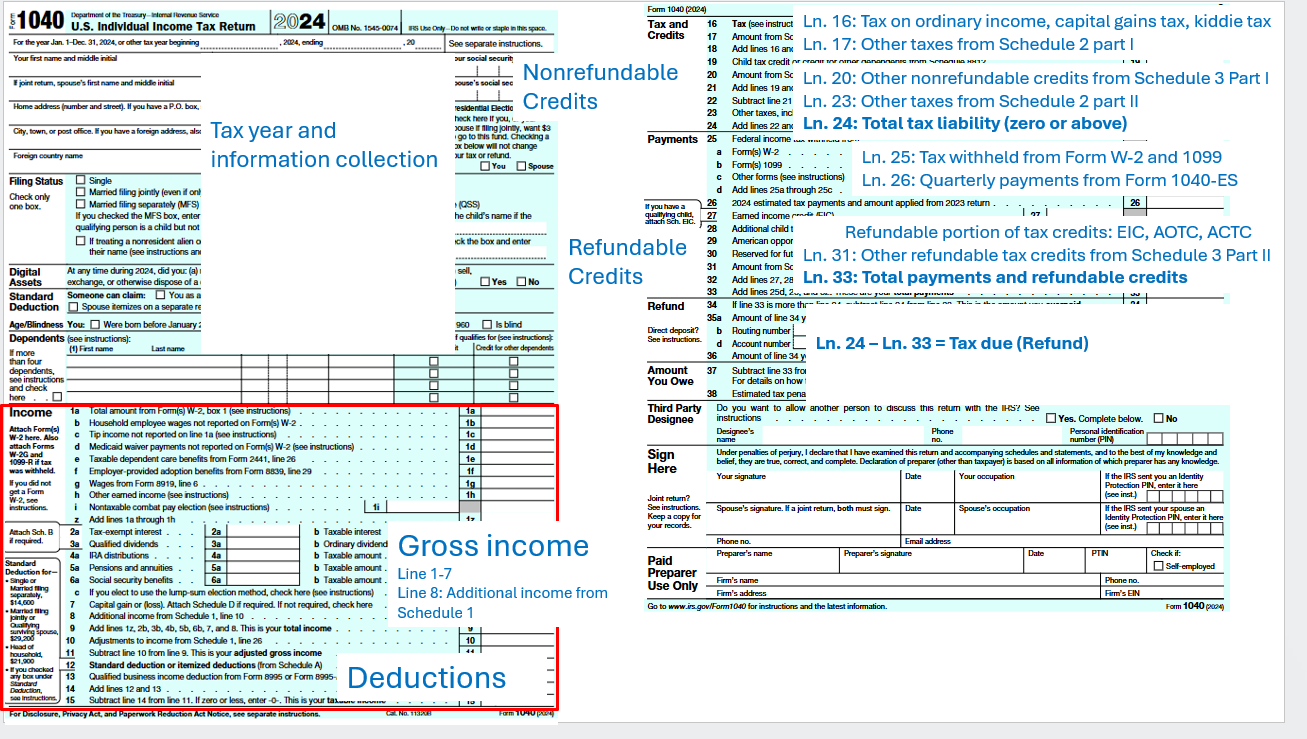

The form begins with identifying information, which includes the taxpayer’s name, address, Social Security number, filing status, and details about dependents. This section ensures that the return is connected to the correct taxpayer and filing situation. The next portion of the form focuses on reporting income. While Form 1040 itself has lines for common income items such as wages, salaries, and tips, less common income sources, like business earnings, capital gains, rental income, or retirement distributions, are reported through supporting schedules, most often Schedule 1.

Once income is reported, taxpayers must determine whether to claim the standard deduction or to itemize deductions. The standard deduction is a fixed amount based on filing status and is available to most taxpayers. Alternatively, those with significant deductible expenses may choose to itemize using Schedule A, which allows them to deduct expenses such as medical costs, state and local taxes, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions. Taxpayers generally select whichever method yields the larger reduction to taxable income.

After deductions, the next step is to apply credits. Tax credits are especially significant because they reduce tax liability on a dollar-for-dollar basis. While some credits are reported directly on Form 1040, others are filed through Schedule 3 or their own specific forms. Examples include the Child Tax Credit, the Credit for Other Dependents, education credits, and the Earned Income Tax Credit. Credits serve not only to reduce taxes but also to encourage certain behaviors or provide relief to targeted groups of taxpayers.

The payments section of Form 1040 reflects taxes already paid during the year. This includes income tax withheld from wages, estimated tax payments, and any overpayments from a prior year that were applied to the current year. These payments are compared to the total tax liability to determine the outcome of the return.

Finally, Form 1040 calculates whether the taxpayer is due a refund or owes additional tax. If total payments and credits exceed the liability, the taxpayer receives a refund. If the liability is greater than payments, the taxpayer must pay the difference. The form concludes with signature lines for the taxpayer(s) and, when applicable, the paid preparer, who must also include their Preparer Tax Identification Number (PTIN).

In addition to the core schedules that accompany Form 1040, such as Schedule 1, Schedule 2, and Schedule 3, along with Schedule A, taxpayers may need to file other supporting forms depending on their circumstances. Common examples include forms for reporting self-employment tax, investment income, or retirement contributions. Together, Form 1040 and its schedules provide a clear, step-by-step framework for reporting income, applying deductions and credits, and determining the taxpayer’s final tax liability with accuracy.