6 Nineteenth-Century Opera

Introduction

Opera continued to be popular in the nineteenth century. In fact, this century became a golden age of opera. As the century began, it was dominated by Italian styles and form, much like it had been since the seventeenth century (even Handel’s operas in London and Mozart’s operas in Vienna were predominantly sung in Italian). There was a time when Italian opera composer Giacomo Rossini was even more popular than Beethoven. By the 1820s, however, other national schools were becoming more influential. Carl Maria von Weber’s German operas enhanced the role of the orchestra, whereas French grand opera by Meyerbeer and others was marked by the use of large choruses and elaborate sets. Later in the century, composers such as Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner would synthesize and transform opera into an even more dramatic genre, and Georges Bizet and Giacomo Puccini would convey gritty realism.

Nineteenth century opera is sometimes described as being comparable in popularity to movies in modern times. If you wanted to take in a story with a big-budget spectacle, you went to the opera.

As you go through this chapter, you’ll be introduced to songs from various operas. If you find anything especially interesting, you could likely find a complete performance of the opera on the internet or from your library. If searching for a video on the internet, try to find a version with subtitles.

Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) was the most popular opera composer in the early nineteenth century. As earlier mentioned, during the 1820s, his music was even more popular than Beethoven’s. While the music world certainly celebrated Beethoven, opera was a better-loved genre than symphonies or chamber music at the time. Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville) and William Tell are still known today from the opening aria “Figaro, Figaro, Figaro,” and William Tell overture, respectively.

Italian Bel Canto Opera

Rossini called his style of opera bel canto, Italian for “beautiful singing.” Indeed, he and subsequent composers wrote stunningly beautiful melodies for the solo voice. To place an even greater emphasis on the voice, the orchestra was sometimes more of a simple support, almost like an accompanying guitar.

This placed a great deal of stardom on the leading lady, or prima donna, of the opera, and by the end of the century, she was called diva, or “goddess.”

Operas stopped using castratos (male singers who are castrated before puberty to retain a higher-pitched voice) in 1821. The artificially high male vocal parts were replaced by the more realistic (though still technically demanding, and high for most singers) tenor.

Rossini’s Barber of Seville is one of the most loved operas of all time. It’s something of a prequel to Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro; Figaro, a barber, helps Count Almaviva and Rosina end up together while scheming against Doctor Bartolo, who wants to marry Rosina. It’s a straightforward–but engaging–plot with likable characters, fun sequences of events, and memorable songs; you’ll likely recognize some of the music.

In contrast to trends we’ll see in many operas, everyone in Barber of Seville lives happily ever after.

Bonus Video: Rossini, Barber of Seville, Figaro’s Aria

In Figaro’s Aria, the title character sings about his life as a barber, describing himself as the handyman of the city as he offers wigs and shaves.

YouTube Video: “The Barber of Seville – Figaro’s Aria” by Gioreto1

Giuseppe Verdi

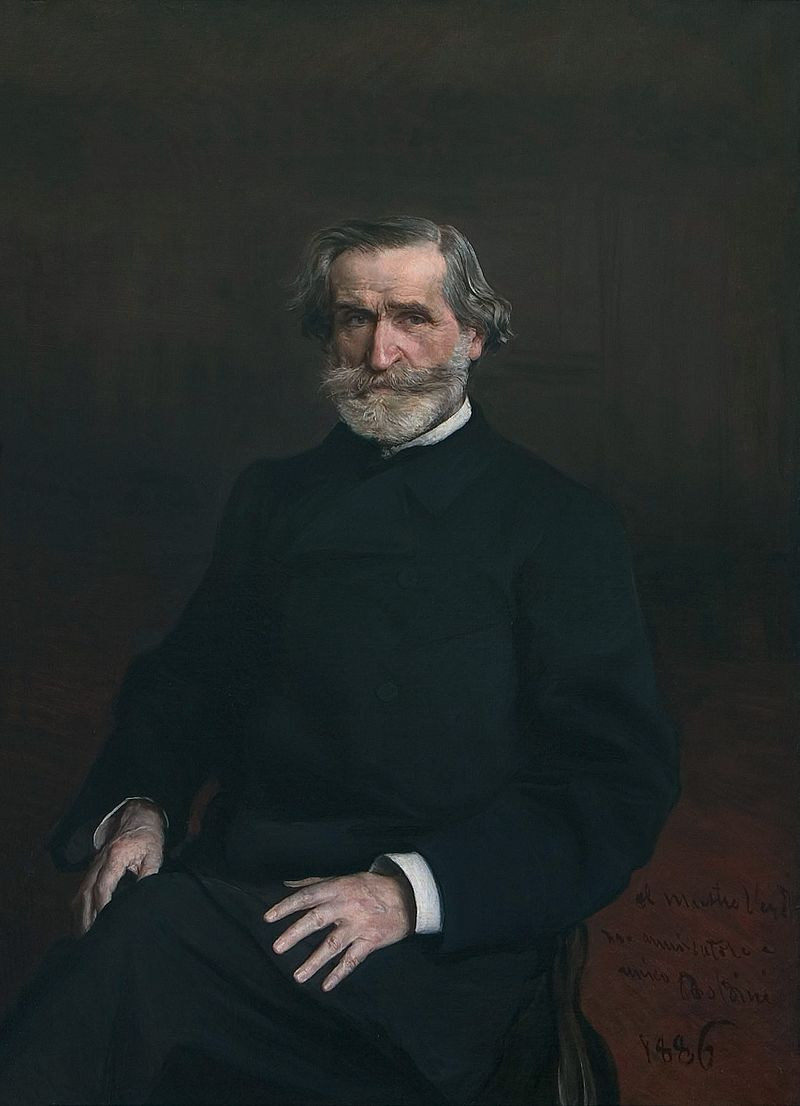

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) succeeded Rossini as the most important Italian opera composer of his day. Living during a time of national revolution, Verdi’s music and name became associated with those fighting for an Italy that would be united under King Emmanuel. His last name, V.E.R.D.I. would become an acronym for a political call to rally around King Emmanuel. Although Verdi shied away from the political limelight, he was persuaded to accept a post in the Italian parliament in 1861.

Verdi was an active composer for half a century, from 1842 to 1893. His works are still widely heard in live and recorded performances, more than any other opera composer. However, his start to music was late compared to other composers we’ve studied. The Milan Conservatory rejected him for admission, and he was nearly thirty years old before his first opera success, Nabucco. Nabucco’s story focused on suppressed Jewish people under Babylonian rule, and contemporary audiences drew parallels to Italy being suppressed by the foreign Austrian government. His choruses were often sung in the streets as protest music.

As was the case with many sons of nineteenth-century middle-class families, Verdi was given many early opportunities to further his education. He began music instruction with local priests before his fourth birthday. Before he turned ten, he played organ at the local church, and he continued music lessons alongside lessons in languages and the humanities throughout his adolescence. He assumed posts as a music director and then in 1839 composed his first opera. Like his predecessor, Rossini, Verdi would prove to be a prolific composer, writing 26 operas in addition to other large-scale choral works. Like Rossini’s music, Verdi’s music used recitatives and arias, now arranged in the elaborate scena ad aria format, with an aria that contained both slower cantabile and faster cabaletta. Verdi, however, was more flexible in his use of recitatives and arias and employed much larger orchestras than previous Italian opera composers, resulting in operas that were as dramatic as they were musical. His operas span a variety of subjects, from consistently popular mythology and ancient history to works set in his present that participated in a wider artistic movement called verismo, or realism.

Verdi wrote La traviata in 1853; it is his most popular work and one of the most performed operas ever. La traviata translates to “The Woman Gone Astray,” and tells the story of an upper-class prostitute, Violetta. She meets Alfredo, who adores her, but Violetta believes no one would truly love her because of her past. After a series of conflicts (Alfredo’s dad disapproves of their relationship), they vow to stay together. She then dies from tuberculosis—but not before singing a show-stopping aria. One description calls it “the ultimate soap opera opera” with over-the-top emotion and music; many of these arias are well-known, including a song where the characters drink to life’s pleasures.

Bonus Video: Verdi, La traviata, “Let’s drink from the joyful cups”

In this scene, Alfredo sings a drinking song to show off his singing abilities. Violetta and the rest of the party join in the singing.

YouTube Video: “La Traviata: ‘Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici'” by Metropolitan Opera

Ex. 6.1: Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi, La traviata, “Follie! Follie!” and “Sempre libera”

In this recitative and aria, Violetta, after pondering if she might have true love with Alfredo, instead discards the idea and vows a life of freedom and independence. “Sempre libera” is an example of cabaletta, a fast aria that dramatically ends the scene.

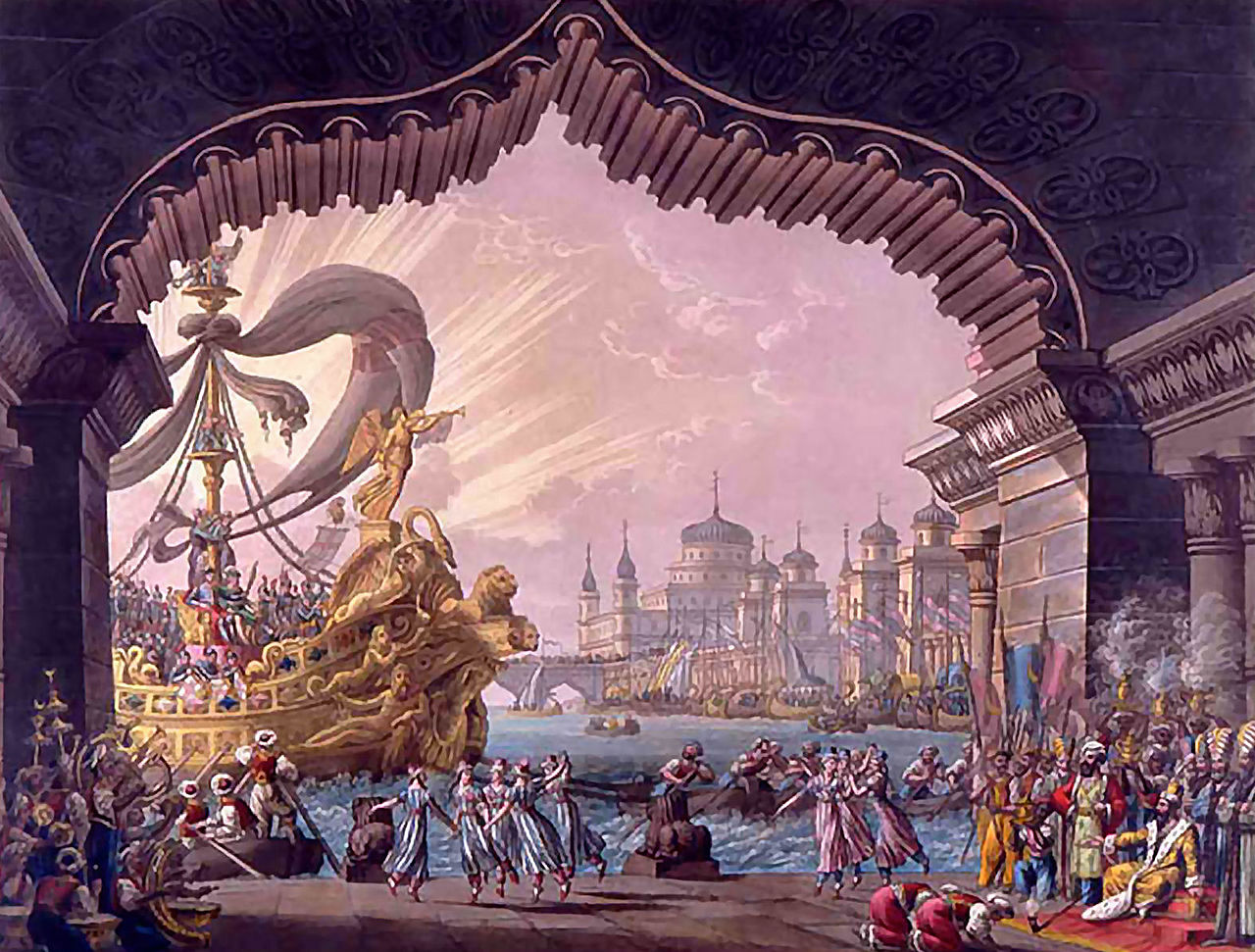

Grand Opera

Grand opera is associated with 19th-century Paris, France. The casts and orchestras became bigger, and the costumes, scenery, and stage effects became more extravagant. The stories usually centered on dramatic moments from history. If attending the 19th-century opera was like going to the movies, grand operas were the big-budget blockbusters.

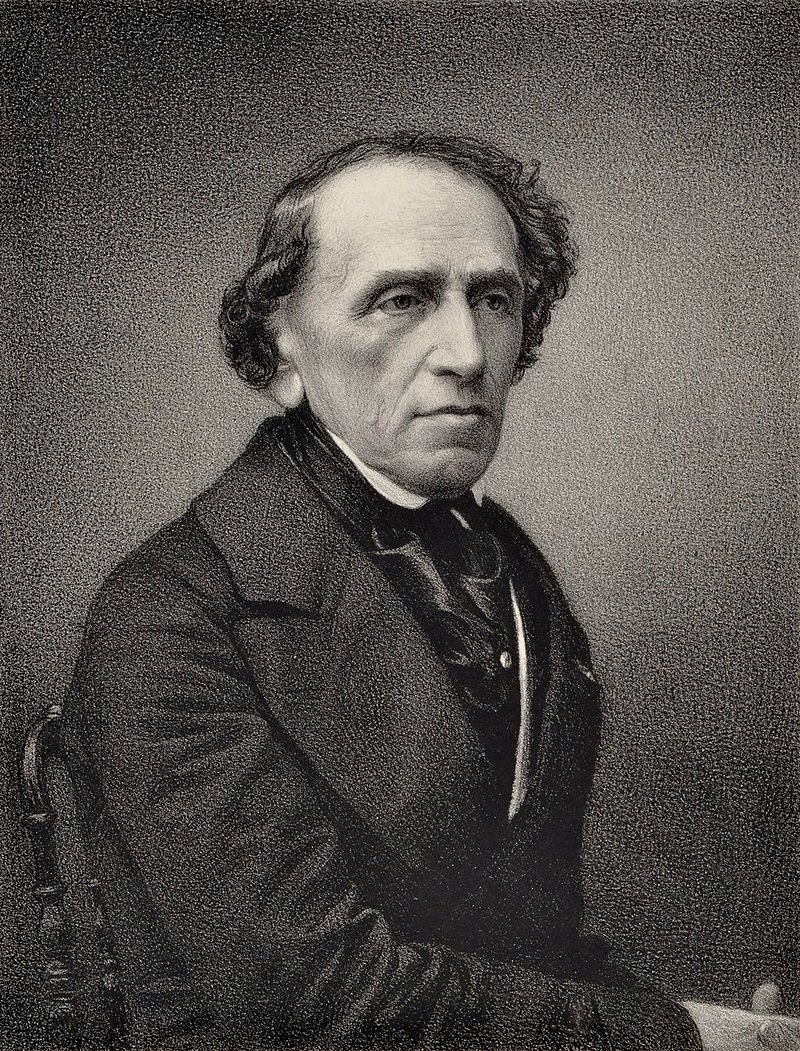

Meyerbeer: The Huguenots

Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) was a Jewish, German composer active in the Paris opera scene. The story involves the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, where French Protestant Huguenots were slaughtered by Catholic forces, and focuses on the love between Catholic Valentine and Protestant Raoul. Per the story, the opera includes the Protestant hymn “Ein Feste Burg,” which focuses on Protestant and Catholic conflicts and contains sword fighting.

Bonus Video: Meyerbeer, The Huguenots, Act V Scene 2

The Protestant protagonists take shelter in a church amidst the ensuing conflict.

YouTube Video: “Meyerbeer, Les Huguenots, Act V, sc. 2” by Michael Cooper

Richard Wagner (1813-1883): A German Opera Style

While the artists of the Renaissance looked back to classical Greece and Rome for inspiration, many of the Romantics looked to the Middle Ages (the time period of Chapter 2). Scholars translated past medieval sagas and poems: the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, the German Song of the Nibelungs, and the Finnish Kalevala. These told stories of castles and dragons, common elements of the fantasy genre today. This rediscovered Nordic literature paralleled Richard Wagner’s work of a German opera style. He used German text, something not commonly done beforehand. Even rarer, he wrote his own librettos, something no other major opera composer had done (remember that even Mozart worked with librettists like La Ponte).

Wagner, born in Leipzig, Germany, was musically self-taught. He learned from the scores of Beethoven. His career is marked by frequent moves due to financial and political troubles. He found success writing a number of German operas set in the Middle Ages, and after reading the recently published German epic Niebelungenlied, he created a massive Ring Cycle—a four-opera story about a coveted ring in a fantasy setting. He intended these operas to be performed on back-to-back-to-back-to-back evenings and spent over two decades working on them. He even raised money to have his own opera house built in Bayreuth, Germany.

Wagner conceived a music drama with unified text, story, music, choreography, and scenery, calling it a Gesamtkunstwerk (German for “total artwork”). While traditional opera had a series of different parts (recitative, aria, chorus), Wagner wrote endless melody: singing and declamation seamlessly follow one another without regard to traditional forms or symmetry. He unified his operas through leitmotifs, recurring melodies that represented characters, situations, or key items. The orchestra also played a tremendous role, conveying the drama with recurring themes. Wagner used a large orchestra of 125 musicians, nearly twenty of which were brass (compare that with a Mozart symphony, which would have two horns and maybe two trumpets). Needless to say, a singer would need an exceedingly powerful voice to sing above that orchestra.

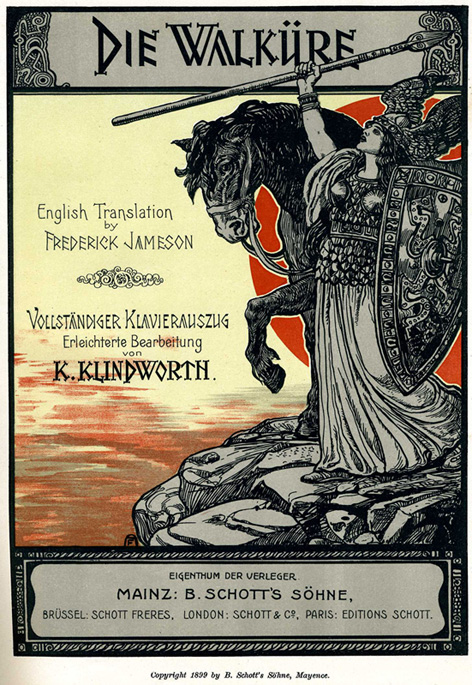

Bonus Video: Wagner, “Ride of the Valkyries,” from Die Walkὒre

This is one of Wagner’s most recognized pieces of music, and is often associated with militaristic conquest. In the opera, the Valkyries, or Norse mythology warrior maidens, bring the dead bodies of fallen heroes to the home of the gods, Valhalla. The music is relentless; there’s barely a moment of silence or a break from the action.

YouTube Video: “Metropolitan Opera Orchestra – Wagner: Ride of the Valkyries – Ring (Official Video)” by Deutsche Grammophon – DG

Ex. 6.2: Wilhelm Richard Wagner, Die Walkὒre, “O hehrstes Wunder”

At this point in the opera, the character Sieglinde has experienced much suffering. In this complicated story, her lover, Siegmund, has been killed. Sieglinde wishes to die too, but changes heart after the Valkyrie Brünnhilde tells Siegmund she’s pregnant with the future hero Siegfried and gives her fragments of a legendary sword that her future son will yield.

Bonus Video

For a two-and-a-half minute summary of the fifteen-hour Ring Cycle, watch:

YouTube Video: “Wagner’s 15-hour Ring Cycle…in two and a half minutes” by Sydney Symphony Orchestra

Bonus Video

For a comedic summary of the fifteen-hour Ring Cycle and its various musical themes, watch:

YouTube Video: “Wagner´s Ring part1” by yvonnedesire

While Wagner is known primarily for his Ring cycle, those operas can be especially complex and difficult to approach (comedic summaries like to point out how one of the characters returns to the plot having inexplicably turned into a dragon). Tristan und Isolde tells the tragic love story of the two title characters. The music creates a sense of longing, with ever-continuing (and gorgeous) melodies and harmonies that don’t seem to resolve until the end of the opera. The story was turned into a popular 2006 film of the same name.

Bonus Video: Tristan and Isolde Prelude

The 10-minute prelude to the opera uses a series of innovative chords that never seem to resolve.

YouTube Video: “Richard Wagner – ‘Tristan und Isolde’, Prelude” by neuIlaryRheinKlange

Realism

Shortly after the 1848 Revolutions throughout Europe and the Industrial Revolution, the artistic movement of Realism emerged. Realism was a reaction against exotic subject matter and exaggerated emotion. It wanted to portray life objectively, and it wasn’t afraid to depict unpleasant subject matters. In music, this appeared as Realistic Opera, which tackled issues including poverty, abuse, and crime. Composers found heroism in the ordinary and bleak.

Georges Bizet’s Carmen (1875)

Bizet (1838-1875) was born in Paris, France. He excelled at the Conservatoire de Paris and won the Prix de Rome composition prize in 1857. However, he did not live to see the eventual success of his most famous work, Carmen.

Carmen was a groundbreaking realistic opera and is Bizet’s lasting masterpiece. Set in nineteenth-century Spain, it tells the story of Carmen, a Romani woman who works in a cigarette factory. She seduces Army Corporal Don José. He falls in love with her, but after Carmen refuses to be tied to any man and give up her life of freedom, he murders her.

Bizet’s Carmen is considered an accessible gateway to opera, and is one of the world’s most popular.

At its premiere, audiences found the work too dismal, and Carmen flopped. Bizet died of a heart attack a few months later. However, with time, and as other artists pursued Realism, Carmen grew in popularity; today it stands as one of the world’s most popular operas ever written.

Ex. 6.3: Georges Bizet, Carmen, “Habanera”

“The Habanera” translates to “the thing from Havana.” It’s a dance-song from nineteenth century Cuba with African and Latin influence. Note the descending chromatic scale in the opening melody with the text “Love is like an elusive bird that cannot be tamed.” This song introduces Carmen as she seductively dances before Don José.

Please note: the character Carmen is often mentioned as being a gypsy; today, the term is considered derogatory and conjures up ethnic stereotypes. Terms like “Romani” are more respectful to use.

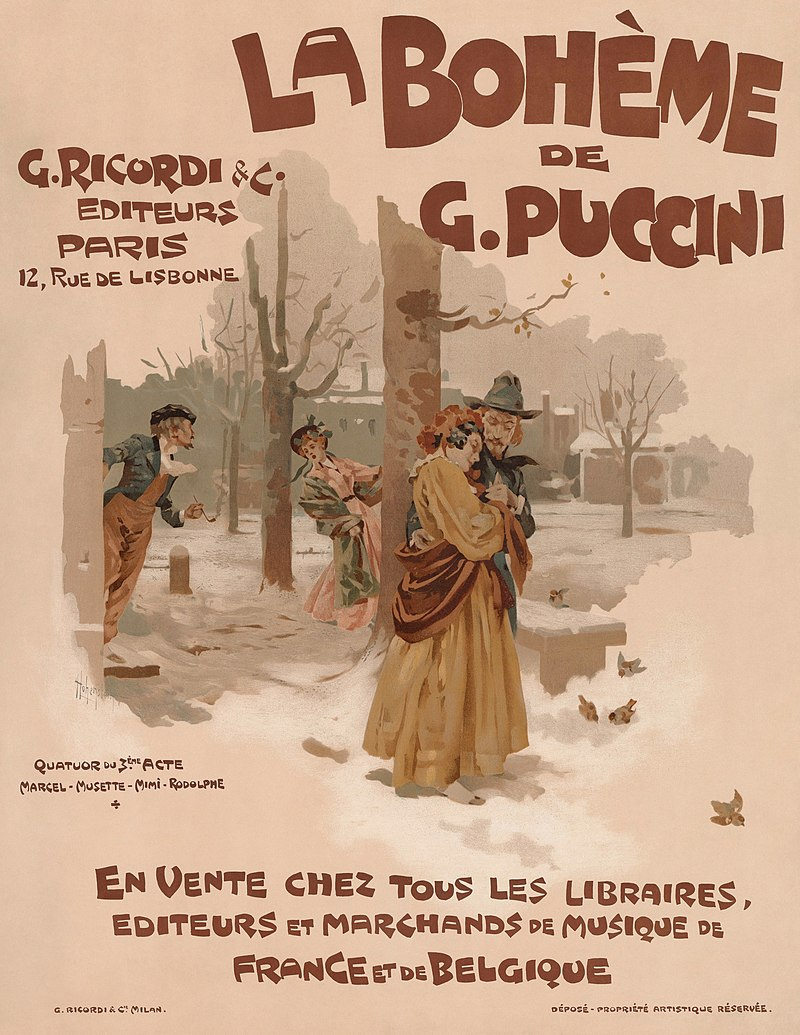

Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème (1896)

After Realistic opera started in Paris, Italian composers incorporated similar ideas which became known as verismo (Italian for “realism”) opera. Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) was the most successful composer of Italian opera after Verdi and is the best-remembered composer of verismo opera. He was born in Lucca, Italy, and his family was something of a musical dynasty. Giacomo was a fourth-generation musician; his father and grandfather were both opera composers.

He lived in poverty after graduating from the Milan Conservatory until the success of Manon Lescaut, which was followed by a string of other successes: La bohème, Tosca, and Madama Butterfly.

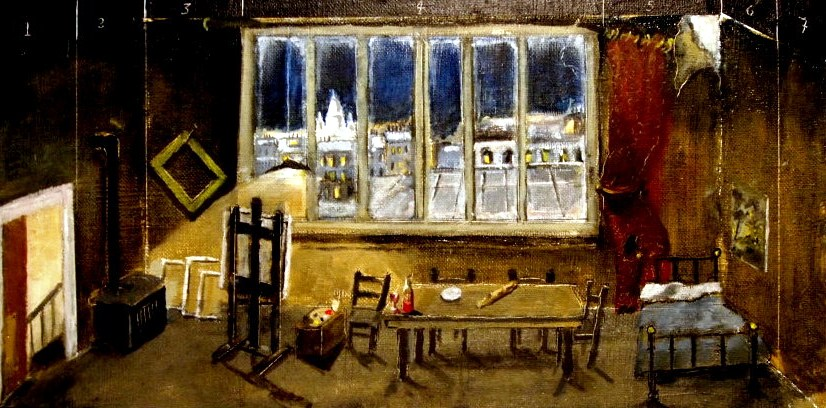

La bohème (“Bohemian Life”) is his most famous work; the characters are artists who live in poverty, and it was the first opera to make city life—particularly its wealth disparities and disease—so prominent in the story. In general, verismo opera juxtaposes life at its most bleak with music—particularly singing—at its most beautiful. This opera is said to have one of the best death scenes in the genre.

Bonus Video: Puccini, La bohème, “Che gelida manina”

This aria introduces the lovers of the opera: Mimi, a poor and sick seamstress, and Rodolfo, a poor poet. Mimi asks for a light for her candle and in their exchange, Rodolfo shares with her his hopes and dreams.

YouTube Video: “La bohème – ‘Che gelida manina’ aria (Puccini; Michael Fabiano, Nicole Car; The Royal Opera)” by Royal Ballet and Opera

Ex. 6.4: Giacomo Puccini, La bohème, “Quando me’n vò”

In the second act, the eponymous bohemians cavort in the bustling Latin Quarter on Christmas Eve. And while Mimì and Rodolfo celebrate their fresh love, the painter Marcello meets his ex-lover—the dazzling Musetta. Musetta sings a short, waltzing aria about all the attention that she receives, and loves receiving, from being beautiful.

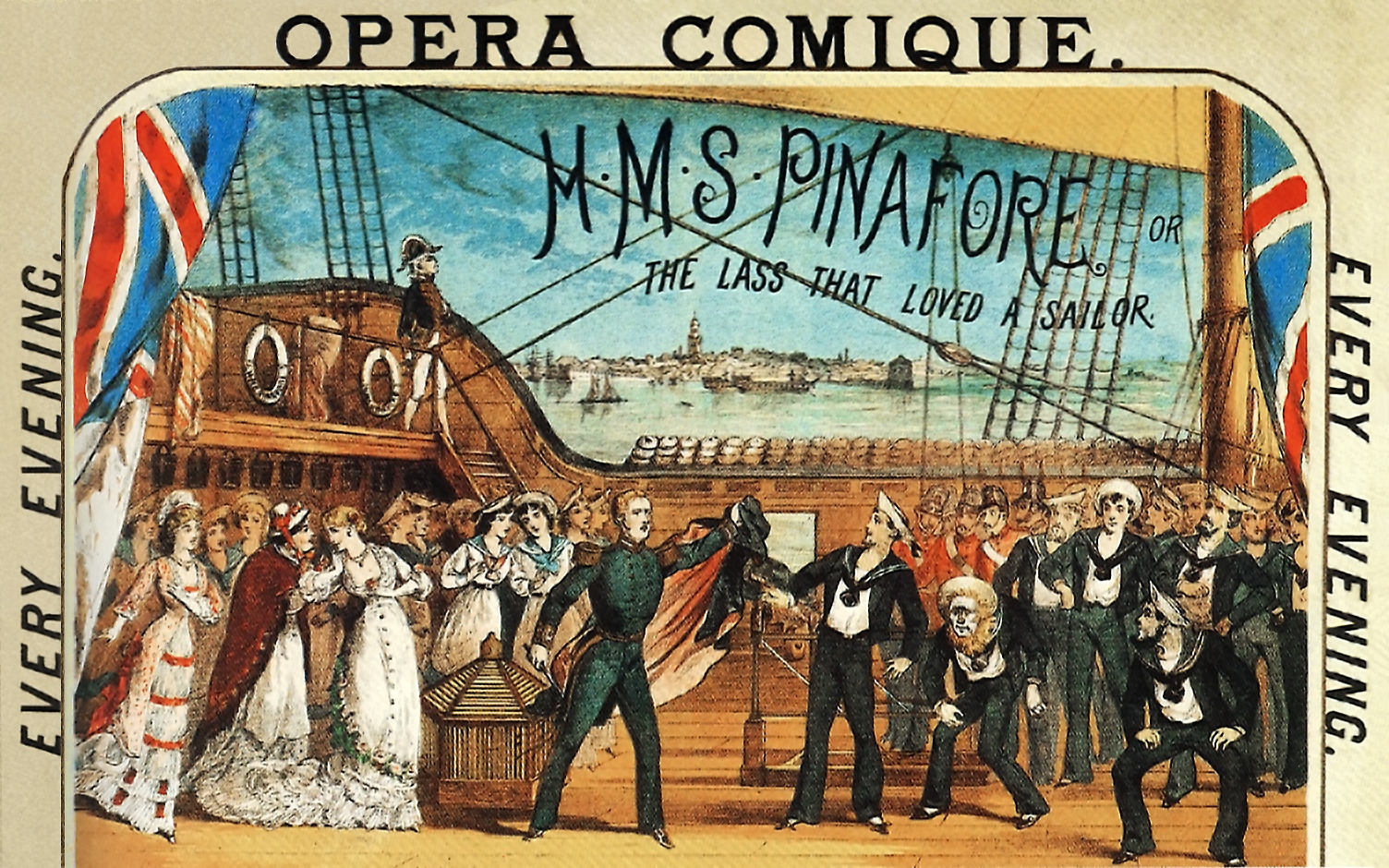

Gilbert and Sullivan and the Savoy Opera

Savoy opera emerged in late nineteenth-century England. Compared to other opera genres, it is light and comedic. This style of opera is named after the Savoy Theatre in the City of Westminster, London, England, a theatre built to show the works of W.S. Gilbert and Sullivan. The term “Savoy Opera” is synonymous with the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Gilbert, the librettist, created absurd stories and Sullivan wrote catchy music. Their work achieved international recognition and influenced twentieth-century musicals.

Ex. 6.5: Gilbert & Sullivan, HMS Pinafore, “Never mind the why and wherefore”

This is a socially-distanced performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. This song from the show HMS Pinafore features the captain, Sir Joseph Porter (First Lord of the Admiralty), and the captain’s Josephine (in love with a sailor, but whom the captain hopes to wed to Sir Joseph).

Bonus Video

The Muppet Show had fun with Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance.

YouTube Video: “Muppet Songs: Gilda Radner – Pirates of Penzance” by Muppet Songs

Opera in the Popular Culture

As we wrap up nineteenth-century opera, let’s sample a few of these memorable melodies from the golden age of opera, many of which have become a part of popular culture through parody, commercials, or simply the power of their music.

Gioachino Rossini’s William Tell: “Call to the Cows”

YouTube Video: “Gioachino Rossini – Guglielmo Tell (Guillaume Tell) – Overture (Chailly) – No. 3 & 4. The call to the dairy cows & The Galop” by LindoroRossini

Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata: “Libiamo ne’ lieti calici” starting at 0:21

YouTube Video: “Verdi – La Traviata: Drinking Song (Libiamo ne’ lieti calici) [HQ]” by The Spirit of Orchestral Music

Giuseppe Verdi’s Il Trovatore: “Anvil Chorus” starting at 1:03

YouTube Video: “Il Trovatore Anvil Chorus Met Opera” by Fredonia Opera House

Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi: “O mio babbino caro”

YouTube Video: “Puccini: Gianni Schicchi: O mio babbino caro” by Giacomo Puccini – Topic

Léo Delibes’ Lakmé: “The Flower Duet”

YouTube Video: “The Flower Duet (Lakmé)” by OpusBoa

Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci: “Vesti la giubba” starting at 1:58

YouTube Video: “Pavarotti – Vesti La Giubba” by Brother Cron

Jacques Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld: “Galop Infernal” starting at 1:48

YouTube Video: “Offenbach – Infernal Galop” by zgred

Attributions

“Beautiful singing,” referring to singing styles of nineteenth century opera.

Primary female vocalist in opera production.

Nineteenth-century operatic combination of a recitative (“scena”) plusaria. Here the aria generally has two parts, a slower cantabile and a faster cabaletta.

Slower and flexible aria, precedes a cabaletta.

Animated aria often conveying strong emotions. Follows a cantabile.

Opera with 4-5 acts, large orchestras, and extravagant staging. Based on historical events.

“Total work of art,” comprised of different artistic forms.

“Guiding motive” associated with a specific character, theme, or locale in a music drama. First associated with the music of Richard Wagner.

Opera genre that highlights “realism.”

Late nineteenth-century English comic opera.