2 The Middle Ages and the Renaissance

Historical Context

Music has existed since prehistory, with rich traditions found throughout the world. So why are we starting with the Middle Ages and Renaissance of Europe? The Medieval and Renaissance periods produced some of the earliest musical works that still exist today. Due to innovations in music notation, and intentional efforts in collecting, transmitting, and preserving this music, these eras include the earliest large collection of surviving music.

It’s worth noting that these eras span a vast amount of time. While the dates are certainly open to debate, the Medieval era lasted from approximately 500-1400 CE, and the Renaissance era in music approximately was from 1400-1600 CE. This is certainly a long time, lasting from the fall of Rome to the beginning of the Baroque.

So why would we group these periods together? Consider, for example, the very different depictions of the same subject matter above, with the late Medieval (left) and Renaissance (right) examples.

Both of these eras set the foundation for subsequent eras of music. Musical ideas that we take for granted today didn’t yet exist; this music was written before the eras which more or less standardized the harmonies, instrumentations, and forms that have been so widely used in the last few centuries.

Additionally, this music isn’t as well known as the future music of Bach and Beethoven. Even the newest music from this chapter is centuries older than what you’re likely to hear in a concert hall.

These time periods also witnessed significant musical developments in both music notation and texture. We’ll see musical developments as church music develops from monophonic chants to polyphonic masses. We’ll see notation emerge and become more complex, and how that allowed for more complex musical performances as performers moved from an oral tradition to manuscripts to the printing press.

During these time periods, we’ll compare and contrast secular and sacred music.

A Sample of Events from History and the Arts

- 7th Century BCE: Ancient Greeks and Romans use music for entertainment and religious rites

- 6th Century BCE: Pythagoras and his experiments with acoustics

- 4th Century BCE: Plato and Aristotle write about music

- From the 1st Century CE: Spread of Christianity through the Roman Empire

- 4th Century CE: Founding of the monastic movement in Christianity

- 4th – 9th Century CE: Development and Codification of Christian Chant

- c. 400 CE: St Augustine writes about church music

- c. 450 CE: Fall of Rome

- 11th Century CE: Rise of Feudalism & the Three Estates (clergy, nobility, common people)

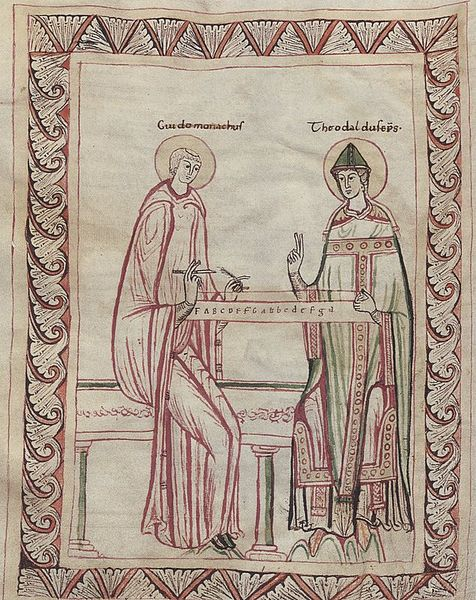

- 11th Century CE: Guido of Arezzo refines of music notation and development of solfège

- 1088 CE: Founding of the University of Bologna (oldest continuously-running university)

- 12th Century CE: Hildegard of Bingen writes Gregorian chant

- c. 1163-1240s CE: Building of Notre Dame in Paris and the rise of Gothic architecture

- 13th Century CE: Development of Polyphony

- 14th Century CE: Further refinement of musical notation, including notation for rhythm

- 1300-1377 CE: Guillaume de Machaut composes songs and church music

- 1346-53 CE: Height of the Bubonic Plague (Black Death)

- 1440 CE: Gutenberg’s printing press

- 1453 CE: Fall of Constantinople

- 1456 CE: Gutenberg Bible

- c. 1475 CE: Josquin Desprez, Ave Maria

- c. 1482 CE: Botticelli, La Primavera

- 1492 CE: Columbus reaches the Bahamas

- c. 1503 CE: Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa

- 1504 CE: Michelangelo, David

- c. 1505 CE: Raphael, School of Athens, Madonna del Granduca

- 1517 CE: Martin Luther nails The Ninety-Five Theses on Wittenberg Church Door

- 1545-1563 CE: Council of Trent

- 1558-1603 CE: Elizabeth I, Queen of England

- 1563 CE: Giovanni Pierluigi da Patestrina, Pope Marcellus Mass

- c. 1570 CE: Titian, Venus and the Lute Player

- 1588 CE: Spanish Armada defeated

- 1597 CE: Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

- 1601 CE: Thomas Weelkes, As Vesta Was Descending

An Introduction to the Middle Ages

We normally start studies of Western music with the Middle Ages, but of course, music existed long before then. In fact, the term Middle Ages or medieval period got its name to describe the time in between (or “in the middle of”) the ancient age of classical Greece and Rome and the Renaissance of Western Europe. Knowledge of music before the Middle Ages is not as extensive, with much of what we know connected to the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, who died around 500 BCE. Again, to emphasize: countless music traditions existed before Pythagoras, but history hasn’t preserved much of that information.

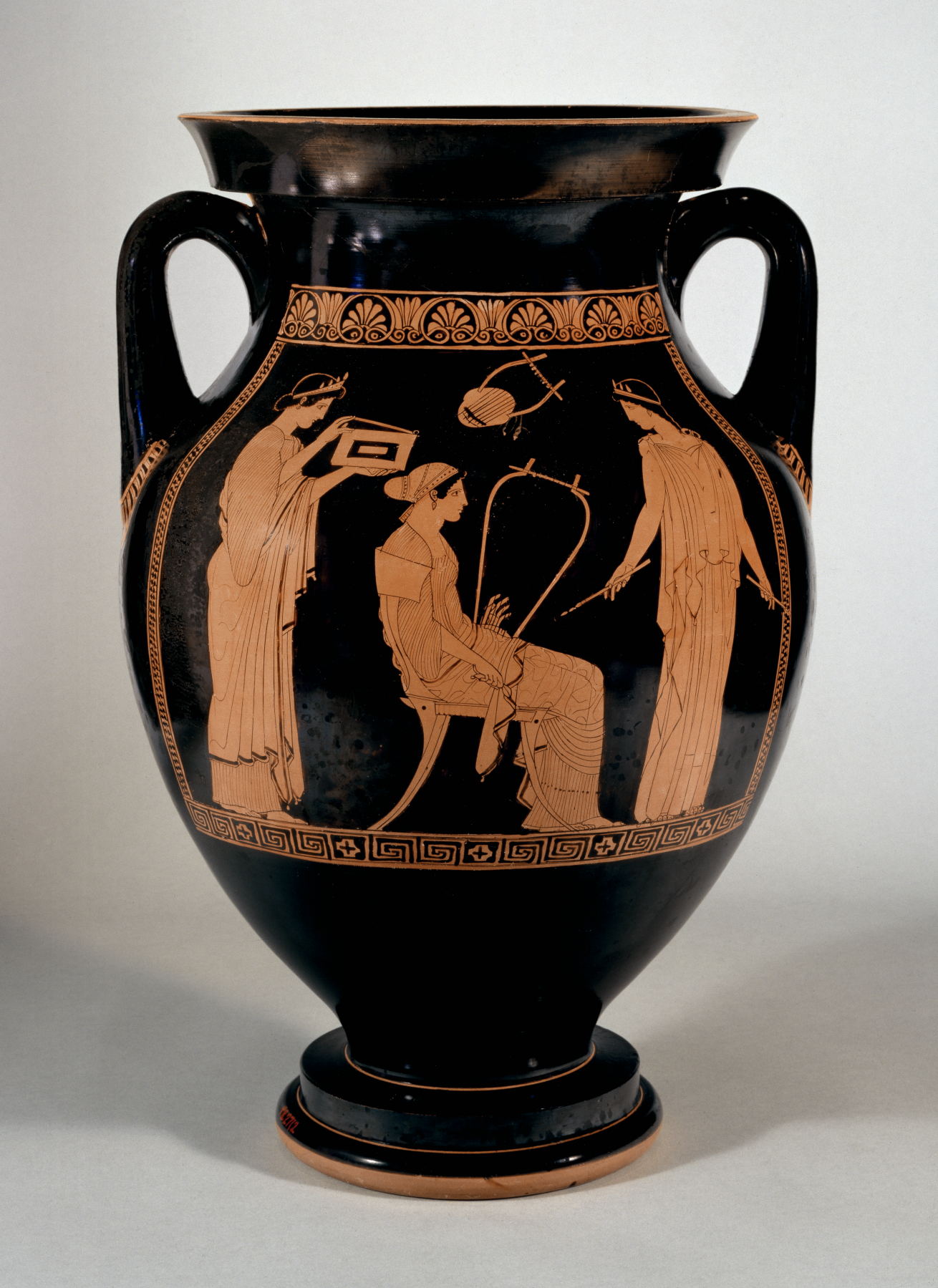

Images of people singing and playing instruments, such as those found on the Greek vases, provide evidence that music was used for ancient theater, dance, and worship. The writings of Plato and Aristotle referred to music as a form of ethos (an appeal to ethics). As the Roman Empire expanded across Western Europe, so did Christianity. The Christian music of this era became one of the earliest, largest collections of music that still exists today. Starting around 800 CE, Western music is recorded in a notation that we can still decipher.

During the Middle Ages in Europe, as during other periods of Western history, sacred and secular worlds were both separate and integrated. During this time, the Catholic Church was the most widespread and influential institution and leader in all things sacred. The Catholic Church’s head, the Pope, maintained political and spiritual power and influence among the noble classes and their geographic territories. The life of a high church official was not completely different from that of a noble counterpart, and many younger children of the aristocracy found vocations in the church. Towns large and small had churches—spaces open to all: commoners, clergy, and nobles. The Catholic Church also developed a system of monasteries, where monks studied and prayed, often in solitude, even while making cultural and scientific discoveries that would eventually shape human life more broadly. In civic and secular life, kings, dukes, and lords wielded power over their lands and the commoners living therein. Kings and dukes had courts—gatherings of fellow nobles—where they forged political alliances, threw lavish parties, and celebrated both love and war in song and dance.

Monasteries, Convents, and Music

For monks in the monastery and nuns in the convent, life was an ongoing schedule of work and prayer, with various worship services throughout the day. Monks and nuns sang plainsong, or Gregorian chant: unaccompanied unison melodies. It dates back from the early Christian church to the time of the Reformation (starting in 1517, when Christian movements outside the scope of the Catholic Church emerged in Europe). It’s named for the music-loving Pope Gregory (540-608). While he didn’t write the chants, he did help collect and organize them. Church musicians began preserving these chants in written form. In addition to preservation, this meant the same music could be shared among different people. The music notation used today evolved from their work. Around the year 1000, those preserving chants introduced a staff of lines and spaces to more precisely measure pitch, and in 1300, different visuals were used to signify different rhythmic durations.

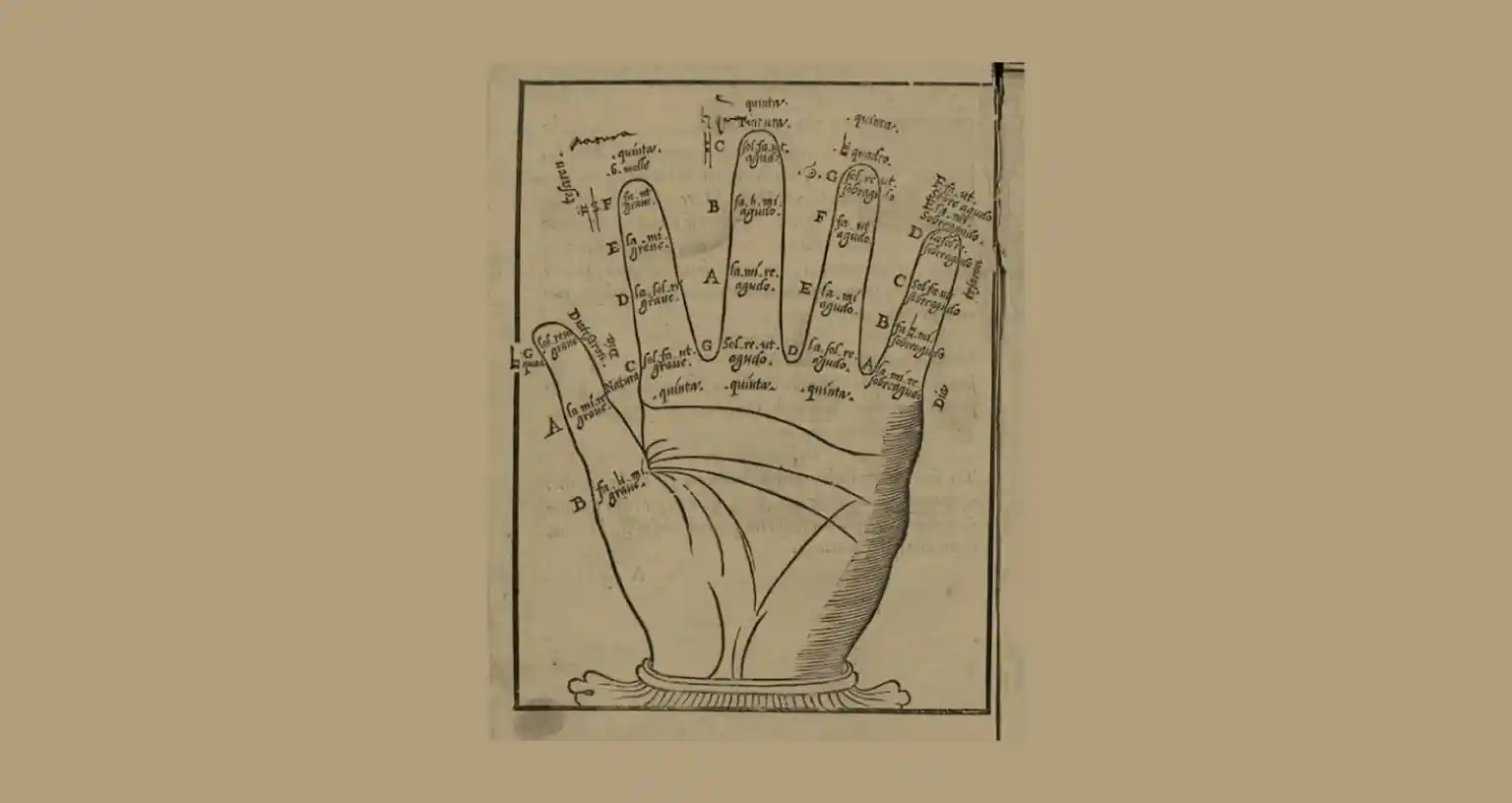

The development of music notation was absolutely critical to the rise of music that used more than just one melody. There are examples of music notation prior to the Middle Ages in Europe that exist; however, Gregorian chant is the earliest large body of notated works that are still well understood today. Effects of music developments due to notation include music of many independent voices (polyphonic), to solo voices with keyboard or group accompaniments, to the popular music we enjoy today. Though modern scholars have found examples of written musical symbols as far back as 900 CE, the staff notation system developed by Guido of Arezzo, and others who followed him, allowed for the accurate preservation and distribution of music. Music notation greatly contributed to the growth, development, and evolution of the many musical styles over the past one thousand years.

Gregorian chant is described as otherworldly, transcendent, meditative, and timeless. In some ways, it is literally “timeless;” there are no recurring rhythmic patterns, and you can’t feel the beat.

Bonus Video: Chant

For a sample of Gregorian chant, check out Chant—this surprise 1994 hit album features the Benedictine Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos in Spain singing ancient chant. It was marketed to help relieve stress; indeed, these monophonic voices and their floating melodies are devoid of dissonance or tension.

YouTube Video: “Canto Gregoriano Católico-Benedictine Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos” by Marcelo Fernandes Ferreira

Bonus Video: More Chant in Popular Culture

Marty O’Donnell, the composer for the hit video game Halo, included music that sounds like Gregorian chant—sparse, floating monophonic melody—in the opening seconds of the main theme. The composer fuses a wide variety of musical influences alongside this Gregorian-like chant with added ambient sounds, rhythmic percussion, additional voices, and active strings.

YouTube Video: “Halo Theme Song Original” by Katlan Youssef

Hildegard of Bingen

Many composers of the Middle Ages will forever remain anonymous. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) from the German Rhineland is a notable exception, and the first composer whose history we know. At the age of fourteen, Hildegard’s family gave her to the Catholic Church where she studied Latin and theology at the local monastery. Known for her religious visions, Hildegard eventually became an influential religious leader. She was also an expert in many fields: science, philosophy, literature, and music. Hildegard was a “Renaissance man” centuries before the start of the Renaissance.

Writing poetry and music for her fellow nuns to use in worship was one of many of Hildegard’s activities, and the hymn “O Virtus Sapientiae” is just one of her many compositions.

Ex. 2.1: Hildegard of Bingen, “O Virtus Sapientiae”

As this is another piece of Gregorian chant, we hear a solo melody that’s rhythmically free-floating. The writing is melismatic; many notes are sung on a single syllable. Note the sparse addition to the texture. While chant is by definition monophonic, scholars suspect that medieval performers sometimes added musical lines to the texture, probably starting with drones (a pitch or group of pitches that were sustained while most of the ensemble sang together the melodic line). Performances of chant music today sometimes elaborate upon the music having a fiddle or small organ play the drone instead of being vocally incorporated. Performers of the Middle Ages possibly did likewise, even if prevailing practices called for entirely a cappella worship.

Listening Guide: Hildegard of Bingen, “O Virtus Sapientiae”

|

Timing |

Latin text |

English translation |

|---|---|---|

|

0:00 |

(vocal drone begin) |

|

|

0:14 |

O virtus Sapientie, |

O Wisdom’s energy! |

|

0:50 |

que circuiens circuisti, |

Whirling, you encircle |

|

0:59 |

comprehendendo omnia |

and everything embrace |

|

1:08 |

in una via que habet vitam, |

in the single way of life. |

|

1:21 |

tres alas habens, |

Three wings you have: |

|

1:30 |

quarum una in altum volat |

one soars above into the heights, |

|

1:44 |

et altera de terra sudat |

one from the earth exudes, |

|

1:52 |

et tercia undique volat. |

and all about now flies the third. |

|

2:01 |

Laus tibi sit, sicut te decet, O Sapientia. |

Praise be to you, as is your due, O Wisdom. |

Organum, Cathedrals, and Early Polyphony

Organum, or chant with an added voice, was introduced in the Middle Ages. This additional voice started as either a supporting bass or a voice moving in parallel motion, but this additional voice became more independent. As texture grew more complex, notation needed to include more precise rhythms. Composers began writing for three or four voices.

Because of his contributions to the development of music notation, Guido of Arezzo is among the most important figures in the development of written music in the Western world. He developed a system of lines and spaces that enabled musicians to notate the specific notes in a melody. As the development of music notation made it possible for composers to notate their music accurately, musicians could perform the music exactly the way each composer intended. This ability allowed polyphonic (many voices) music to evolve rapidly; the clearer the pitch and rhythm notation, the easier it was to coordinate multiple moving parts.

One important development stemming from the Catholic Church was the development of architecture. During this period, architects built increasingly tall and imposing cathedrals for worship through the technological innovations of pointed arches, flying buttresses, and large cut

glass windows. This new architectural style (example below right in Figure 2.10) was referred to as “gothic,” which vastly contrasts the earlier Romanesque style (example below left in Figure 2.9), with its rounded arches and smaller windows.

During the height of Gothic Cathedral construction, Machaut wrote the first polyphonic setting of the mass—the Catholic celebration of the Eucharist consisting of liturgical texts set to music.

Machaut, Gloria or Messe de Notre Dame

Machaut was the first composer to write a setting of the Mass Ordinary—the five parts of the mass sung in every church service. One of the voice parts the tenor—sings a preexisting chant while three other voices sing additional melodies. Machaut used a wider vocal range of the choir compared to earlier sacred composers. Additionally, this work alternates between monophonic and polyphonic textures.

Harmonically, this music is very different from later classical music. The different harmonies we hear in this piece result more from combining different melodies than they do from using standard chords, with moments before cadences often having sharp dissonances and the cadences themselves being dissonant, with the natural reverb of the Gothic cathedral making the dissonances sound all the more chaotic and the consonances so much more of a relief.

Bonus Video: Machaut, Messe de Nostre Dame

You can listen to a YouTube performance that includes sheet music here:

YouTube Video: “Machaut: Messe de Nostre Dame -II. Gloria in excelsis Deo” by 411nave

Music of the Courts

Most of the music discussed in the chapter so far has been sacred music. Music was also prevalent in the secular world (though less of it survives in written notation compared to Gregorian chant). In the courts of the upper class, particularly the French, poet-musicians called troubadours (in Southern France) and trouvères (in Northern France) sang news, gossip, and chansons, or lyric-driven songs. The aristocracy supported these musicians, and some of the upper class actively participated in the arts.

Ex. 2.2: Theobald I of Navarre, Estampie Royale

Theobald I of Navarre was a trouvère as well as a ruler. “Estampie Royale” is one of his surviving compositions. Estampies are some of the oldest examples of composed instrumental music that still exist today. They include repeating melodies. In this performance, one of the instrumentalists improvises an introduction; the different instruments play the same melody, creating a homophonic texture which eventually includes percussion accompaniment. An improvised solo concludes this performance.

In the courts of the Middle Ages, women often participated in music and poetry. Beatriz, Countess of Dia, was a composer who lived in twelfth-century Southern France. Her chanson “A chantar m’er” sings of unrequited love. In this recording, the vielle, a stringed instrument, provides an introduction and simple accompaniment along with percussion to the first of five strophes. You can hear a sample of this piece below:

Bonus Video: Beatriz, Countess of Dia, A chantar m’er

YouTube Video: “Beatriz de Dia: A chantar m’er de so q”ieu no voldria” by micrologus2

An Introduction to the Renaissance

The term renaissance literally means “rebirth.” As a historical and artistic era in Western Europe, the Renaissance spanned from the late 1400s to the early 1600s. The Renaissance was a time of waning political power in the church, somewhat as a result of the Protestant Reformation. Also during this period, the feudal system slowly gave way to developing nation-states with centralized power in the courts. This period was one of intense creativity and exploration. It included such luminaries as Leonardo da Vinci, Ferdinand Magellan, Nicolaus Copernicus, and William Shakespeare.

The Renaissance provided the thinkers and scholars of the day with a revival of Classical (Greek and Roman) wisdom and learning after a time of papal restraint. This “rebirth” laid the foundation for much of today’s modern society, where humans and nature, rather than religion, become the standard for art, science, and philosophy.

The School of Athens (1505), Figure 2.16, by Raphael, demonstrates the strong admiration, influence, and interest in previous Greek and Roman culture. The painting depicts the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato (center), with Plato depicted in the likeness of Leonardo da Vinci.

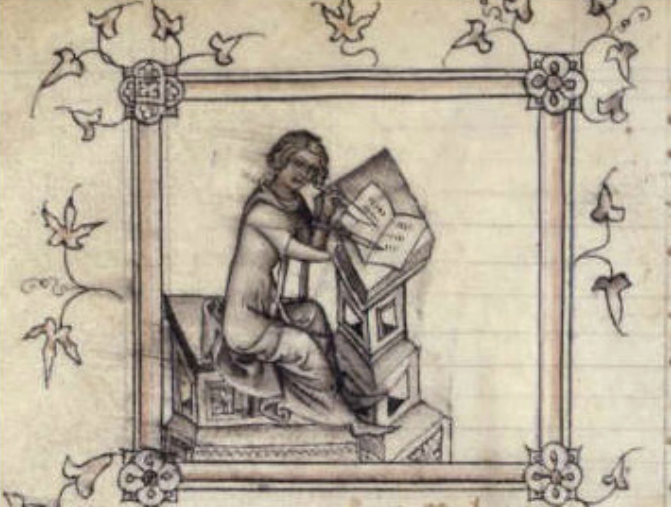

Few inventions have had the significance to modernization as the Gutenberg Press. Up until the invention of the press, the earliest forms of books with edge binding, similar to the type we have today, called codex books, were hand-produced by monks. This process was quite slow, costly, and laborious, often taking months to produce smaller volumes and years to produce a copy of the Bible and hymn books of worship. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of a much more efficient printing method made it possible to distribute a large amount of printed information at a much accelerated and labor-efficient pace. The printing press enabled the printing of hymn books for the middle class and further expanded the involvement of the middle class in their worship service—a key component in the Reformation. Gutenberg’s press served as a major engine for the distribution of knowledge and contributed to the Renaissance, Scientific Revolution, and Protestant Reformation.

The Humanism movement is one that expresses the spirit of the Renaissance era that took root in Italy after Eastern European scholars fled from Constantinople, bringing with them books, manuscripts, and the traditions of Greek scholarship. Humanism is a major paradigm shift from the ways of thought during the medieval era where a life of penance in a feudal system was considered the accepted standard of life. As a part of this ideological change, there was a major intellectual shift from the dominance of scholars and clerics of the medieval period (who developed and controlled the scholastic institutions) to the secular men of letters. People of letters were scholars of the liberal arts who turned to classic works of literature and philosophy to understand the meaning of life.

Humanism has several distinct attributes as it focuses on human nature, its diverse spectrum, and all its accomplishments. Humanism syncretizes all the truths found in different philosophical and theological schools. It emphasizes and focuses on the dignity of man, and studies mankind’s struggles over nature.

Renaissance Music

As the Middle Ages gave way to the Renaissance, people documented more information about not just the music itself, but also the composers. Two prominent names emerged: Josquin Des Prez (ca 1450-1521) and Palestrina (1525-1594). Des Prez was commended by people as diverse as Castiglione and Luther for his musical genius. He also sang in the newly renovated, at that time, Sistine Chapel. Palestrina, the most prominent composer during the Counter-Reformation, epitomized Renaissance polyphony and served as a model for subsequent composers.

Josquin Des Prez

Many in the Renaissance recognized Josquin as the greatest composer of his day; he was compared in excellence to Renaissance artist Michelangelo. Protestant reformer and hymn writer Martin Luther said, “Josquin is master of the notes, which must express what he desires; on the other hand, other composers must do what the notes dictate.” Josquin was born near France and Belgium, but moved for greater job opportunities. Josquin spent much of his time serving in chapels throughout Italy and partly in Rome for the papal choir. He sang in the Sistine Chapel; graffiti on the wall of the Chapel appears to depict his name. Later, he worked for Louis XII of France and held several church music directorships in his native land.

A contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci and Christopher Columbus, Josquin des Prez was a master of Renaissance choral music. He wrote all styles of music and especially excelled at writing motets—sacred choral works with Latin texts. Motets could be sung in public worship in church or in private meditation at home.

The motet, a sacred Latin text polyphonic choral work, is not taken from the ordinary of the mass. Josquin’s “Ave Maria …Virgo Serena ”(“Hail, Mary … Serene Virgin”) ca. 1485 is an outstanding Renaissance choral work.

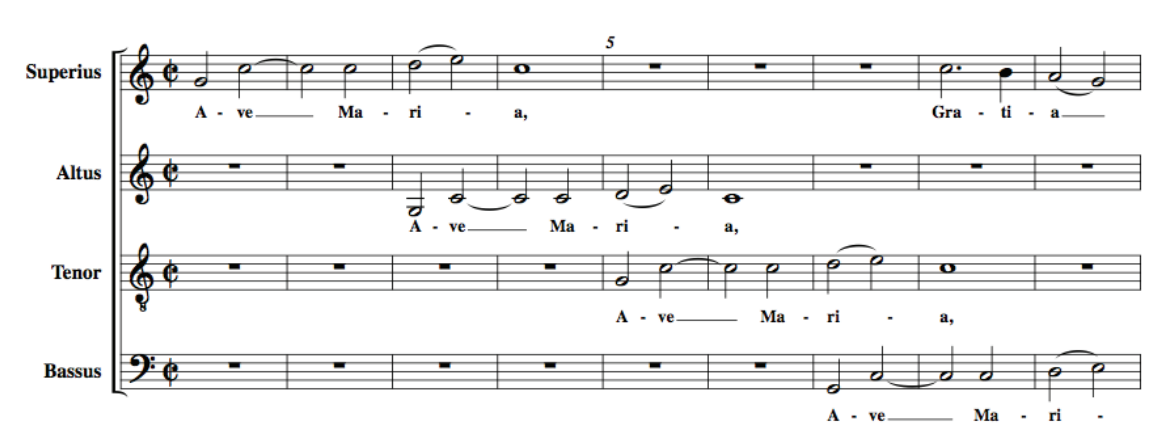

Ex. 2.3: Josquin Des Prez, “Ave Maria”

A four part (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) Latin prayer, the piece weaves one, two, three, and four voices at different times in polyphonic texture.

Bonus Video: Josquin des Prez, “Ave Maria”

Additionally, watch this YouTube video of the piece with a graphic animated score. Listen (and in the YouTube video, watch) for imitation, as the same musical motive moves from voice to voice.

YouTube Video: “Josquin des Prez, Ave Maria (virgo serena, motet)” by smalin

The Reformation, Counter-Reformation, and Palestrina

Prior to the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, Western Europe was religiously united under the Roman Catholic Church. In the Middle Ages, people were thought to be parts of a greater whole: members of a family, trade guild, nation, and church. At the beginning of the Renaissance, a shift in thought led people to think of themselves as individuals. Additionally, Martin Luther sparked dissent against several areas and practices within the Catholic Church. On October 31, 1517, Luther challenged the Catholic Church by posting The Ninety-Five Theses on the doors of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. The post stated Luther’s various beliefs and interpretations of Biblical doctrine which challenged the many practices of the Catholic Church in the early 1500’s. With the invention of the Gutenberg Press, copies of the scriptures and hymns became available to the masses which helped spread the Reformation. The empowerment of the common worshiper or middle class continued to fuel the loss of authority of the church and upper class.

After much of Europe became Protestant, the leaders of the Catholic Church met to discuss reform. This launched the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent, which impacted church practice and the arts. One concern was that music had grown too complex; sacred texts were getting buried in all of the polyphony and imitation, and the rhythms were too distracting. Some proposed an outright ban on polyphony. Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, the most important composer during this time, wrote the Missa Papae Marcelli, which showed that restrained polyphonic music could both clearly and artistically deliver these sacred texts. Devoting his career to the music of the Catholic Church, Palestrina served as music director at St. Peter’s Cathedral and composed 450 sacred works and 104 masses.

Ex. 2.4: Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Pope Marcellus Mass, “Santus”

Generally, the music is consonant (to contrast, the Machaut we earlier heard was filled with dissonance), which creates a sense of serenity and peace.

The Latin text translates to:

Holy, Holy, Holy Lord God of hosts.

Heaven and Earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest.

Bonus Video: Palestrina, Pope Marcellus Mass, “Kyrie”

The Kyrie sets a total of four Latin words: “Kyrie eleison” (Lord have mercy upon us) and “Christe eleison” (Christ have mercy upon us). While critics of polyphony complained that imitation and polyphony could muddy the clarity of a text, Palestrina used them in such a way that the text was clear.

YouTube Video: “Kyrie – Missa Papae Marcelli – Palestrina” by morphthing1

Popular Music in the Renaissance

Compared to the Middle Ages, where most secular music was learned by oral tradition, we have a far better idea of what secular music in the Renaissance sounded like. With the invention of the printing press, music was copied by the hundreds. This meant songs were more widely circulated, and more copies meant more music could be preserved for future generations.

Madrigal

The sixteenth century saw an explosion in the popularity of madrigals, secular works for several solo voices. With the printing press, sheet music was significantly more accessible, and books of madrigals flourished. Word painting was a characteristic feature, as composers would write musical phrases that reflected the text.

Thomas Weelkes, a church organist and composer, became one of the finest English madrigal composers. Thomas Weelkes’ “As Vesta Was Descending” serves as a good example of word painting with the melodic line following the meaning of the text in performance.

Ex. 2.5: Thomas Weelkes, “As Vesta Was from Latmos Hill”

Weelkes’ madrigal uses words like “descending” with falling pitches and “ascending” with rising pitches, especially in the phrase “Diana’s darlings came running down amain,” when each of the six voices has a recurring running melodic descent.

Songs with Instruments

Instrumental music in the Renaissance remained largely relegated to social purposes such as dancing, but a few notable virtuosos of the time (extremely talented performers), including the English lutenist and singer John Dowland, composed and performed music for Queen Elizabeth I, among others.

Dowland was a lutenist in 1598 in the court of Christian IV and later in 1612 in the court of King James I. He is known for composing one of the most popular and remembered songs of the Renaissance period, “Flow, my Tears.” This imitative piece demonstrates the melancholy humor of the time period.

Ex. 2.6: John Dowland, “Flow My Tears”

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and the time of William Shakespeare, much literature and music expressed themes of sadness, darkness, the cruelty of fate, and death’s inevitability. The words of the text express a sense of hopelessness.

The Renaissance and Musical Experimentation

The Renaissance was a time of discovery and experimentation; in some circles, this very much applied to music. Musicians experimented with tunings, divisions of the octave, and virtuosity. Chromaticism—using notes between those found in a scale—was likened to scientific experimentation; harmonic tension could help convey a sense of nature, and originality was considered an important trait for a Renaissance composer. The concept of “virtuoso music” emerged—music that appealed to advanced performers and listeners, connoisseurs of the most daring styles.

Vicente Lusitano was a music theorist and composer of Portuguese and African descent. He is recognized as the first Black composer to be published with his treatise on polyphony, printed in Rome in 1553.

Ex: 2.7: Vicente Lusitano, “Heu me Domine”

This work served as an example of chromatic polyphony in a treatise attributed to Lusitano. Notes are continually moving by half-step; half-steps, or chromatic alterations, were common at cadences, but it was unique to hear melodies this chromatic, blurring senses of key and scale.

Listening Guide: Vicente Lusitano, “Heu me Domine”

|

Timing |

Latin text |

English translation |

Musical description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

0’08 |

Heu me, Domine, |

Alas for me, Lord |

Each voice slowly ascends chromatically, rising slightly to the word “Lord” |

|

0’30” |

quia pecavi nimis in vita mea: |

because I have sinned too much in my life: |

The melody twists around the words “too much” |

|

0’52” |

quid faciam miser, ubi fugiam,

|

what shall I do, wretched, where shall I flee, |

After a continued chromatic ascent, the soprano and bass voices reach their highest notes on the word “wretched,” and then descend downward for the phrase “where shall I flee” |

|

1’10” |

nisi ad te, Deus meus?

|

but to thee, God of mine? |

Each voice repeats the phrase “but to thee, God of mine,” and each voice settles into the lower part of their range, holding out the word “mine” |

|

1’38” |

Libera me, Domine, |

Free me, Lord, |

Like the beginning, each voice slowly ascends chromatically, rising slightly to the word “Lord” |

|

1’52” |

Libera me, Domine, de morte æterna, |

Free me, Lord, of death eternal,

|

As these two phrases overlap, the melodies for the phrase “of death eternal” fall, using comparatively larger intervals |

|

2’13” |

de morte æterna,

|

of death eternal,

|

Each voice concludes the phrase “of death” or “of death eternal” as the soprano displays the most rhythmic activity of the entire piece |

|

2’16” |

in die illa tremenda, |

on that terrible day |

Compared to the previous phrases, there’s less melodic motion. |

|

2’30” |

quando celi mouendi sunt et terra. |

when the heavens are moving and also the earth. |

Many of the melodies slowly descend chromatically, leaping upward only to continue another chromatic descent. |

Meanwhile, Throughout the World

Most of the surviving records of Western music document trends and histories in Europe. A brief sample of other music throughout the world during these time periods include:

Ca. 1000 CE – Gagaku, or “elegant music” is established as a Japanese classical music of the imperial courts.

Ca. 1000 CE – Copper and clay bells are constructed and traded in the Mississippi Valley and Mexico.

Ca. 1300 CE – Musicians in the Pueblo region of the Rio Grande used percussion stones; these stones were found by later researchers.

Ca. 1500 CE – In the classical music of India, the Hindustani style of the north and the Carnatic style of the south are established.

1565 CE – At St. Augustine, Florida, the first permanent European settlement in the future United States is created. The music in this Spanish settlement is both Spanish and African, of slaves and free Black people.

1598 CE – The earliest known European music education in the United States, taught by Spanish friars, takes place in a Spanish colony in New Mexico.

Attributions

Religious; music used for church.

Non-religious; music used in courts or public spaces.

Text set to a melody written in monophonic texture without notated rhythms, sung by medieval European Christian monks and nuns.

More than one note sung during one syllable of the text.

Plainchant medieval melody accompanied by least one additional melody.

Catholic celebration of the Eucharist consisting of liturgical texts set to music.

The ending of a musical phrase providing a sense of closure, often through the use of one chord that resolves to another.

A reflection or echo of sound as it bounces off surfaces before decaying.

Poet-musicians in Southern France.

Poet-musicians in Northern France.

Lyric-driven French songs, usually secular.

Lively Medieval dance in triple meter.

Highly varied and polyphonic sacred choral musical composition.

A musical piece for several solo voices set to a short poem, often about love.

Utilized by composers to represent poetic images musically. For example, an ascending melodic line would portray the text “ascension to heaven.” Or a series of rapid notes would represent running.

Someone with outstanding technical talents and skills.

Musical pitches which move up or down by successive half-steps, or music which uses notes that are not a part of the predominant scale of a composition or one of its sections.