10 Art Music after 1945

Introduction

In Chapter 7’s discussion on Modernism, we say a variety of “isms,” or different artistic trends, styles, and aesthetics: Impressionism, Neoclassicism, Primitivism, Expressionism, Twelve-tone music, etc. As art composers created new music after World War II, a proliferation of styles continued, with varied aesthetics influenced by music of the past, different music from around the world (some of which we sampled in Chapter 8), popular music (Chapter 9), and new artistic philosophies and the creations of completely new sounds.

World War II is widely regarded as the deadliest conflict in human history in terms of total deaths, partly due to advancements in technology such as machine guns, tanks, and eventually the atom bomb. It’s no surprise that the new music of this era mirrored the urgency and turmoil in the world at large.

In the aftermath of World War II, Postmodernism emerged. Where the Modernism of the early twentieth century was reactive against earlier traditions, Postmodernism abandoned them. In Postmodernism, anything can become art, with little distinction between high and low art. For example, Andy Warhol’s depictions of Campbell Soup cans and pop culture icon Marilyn Monroe could be displayed in the same spaces that housed masterworks of the Renaissance. It’s also worth noting that works that were less aesthetically challenging or abstract compared to Modern works were being celebrated again.

Any artifact of any culture or style can be of merit. And speaking of culture, it’s worth noting the decreasing cultural differences throughout the world through globalization. A plane ride can take you almost anywhere in the world in less than a day. Breaking news from one corner of the world can reach the entire globe in minutes. And there’s also homogenized popular music and popular culture. While it’s wonderful to have near-instant access to countless news stories and styles of music, homogenization also means that less common languages risk disappearing. To use one example, Icelandic, a language only widely spoken in the country of Iceland with its 360,000 residents, was far less commonly integrated into smartphones and smart speakers compared to English. If new technologies neglect languages, how do those languages remain prevalent?

As we’ve seen before, boundaries in style can blur. For example, what one considers Modern, another could conceivably consider Postmodern.

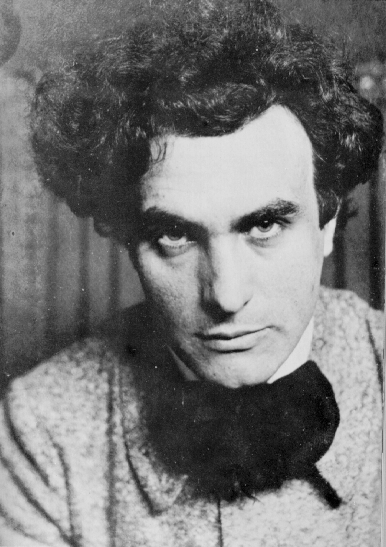

Edgard Varèse (1883–1965) and Electronic Music

Edgard Varèse was born in France and relocated to the United States in 1915. In his first composition written in the United States, Amériques, he wrote for traditional instruments like string, brass, and woodwind, but also called for new percussion instruments like sleigh bells and sirens. He started writing pieces using only percussion instruments, like Ionization; instruments earlier used for accents or keeping the beat now comprised all of the music. He was especially inspired by the new sound possibilities of electronic music.

Bonus Video: Varèse, Poème électronique

This music was originally heard at the Brussels World’s Fair in a 425-speaker pavilion commissioned by the Philips corporation and included a video montage. It contains a collage of edited sounds—some natural, some electronic. This style of music can be very difficult to approach. It’s perfectly okay if you don’t particularly enjoy it, but it is important to listen to it to better understand how it operates; note how some sounds recur throughout the composition.

YouTube Video: “Varese-Edgard-and-Le-Corbusier_Poeme-Electronique_1958” by WEIRDERSIDE COUNTY

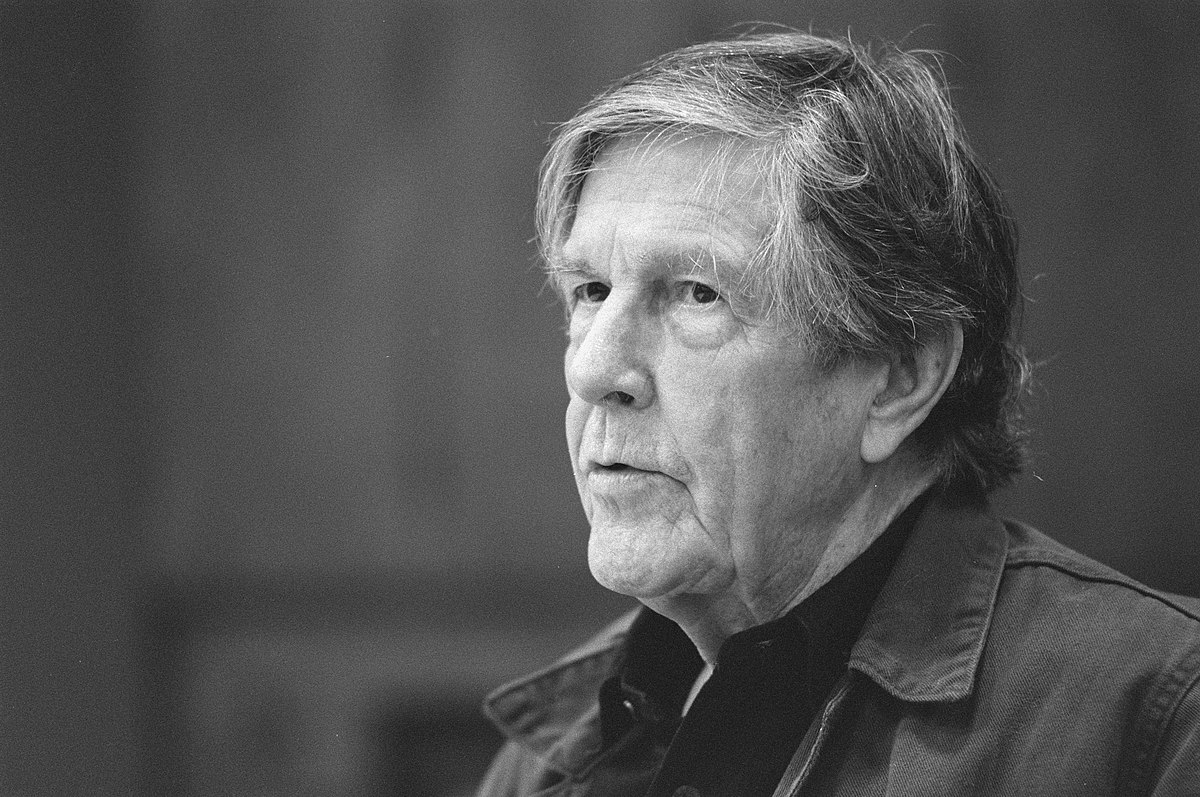

Jon Cage (1912-1992) and Chance Music

John Cage grew up in Los Angeles, studied in Europe, and relocated to New York City. He was especially intrigued with percussion instruments and making percussion sounds with found objects—anything that might make an interesting noise. This led to his innovation of the prepared piano: a piano with different items—screws, erasers, plastic, etc.—inserted into the strings to alter the sounds.

Cage, who was also interested in Eastern philosophies, often created chance music—using elements like flipping a coin or rolling a dice to determine what would next happen in a piece of music.

Bonus Video: Cage, Sonata V (from Sonatas and Interludes)

YouTube Video: “John Cage – Sonata V (from Sonatas and Interludes) – Inara Ferreira, prepared piano” by Inara Ferreira

Bonus Video: Cage, 4’33”

He’s especially known for his composition 4’33”; in this work, the performer doesn’t play anything for 4 minutes and 33 seconds. This time duration provides a framework for the listener to focus on any and every sound—creaking chairs, crinkling music programs, breathing, etc.

Something to think about: in Chapter 8, we looked at the concept of ma in Japanese music. How does that relate to the music of John Cage?

YouTube Video: “John Cage: 4’33” for piano (1952)” by Armin Fuchs

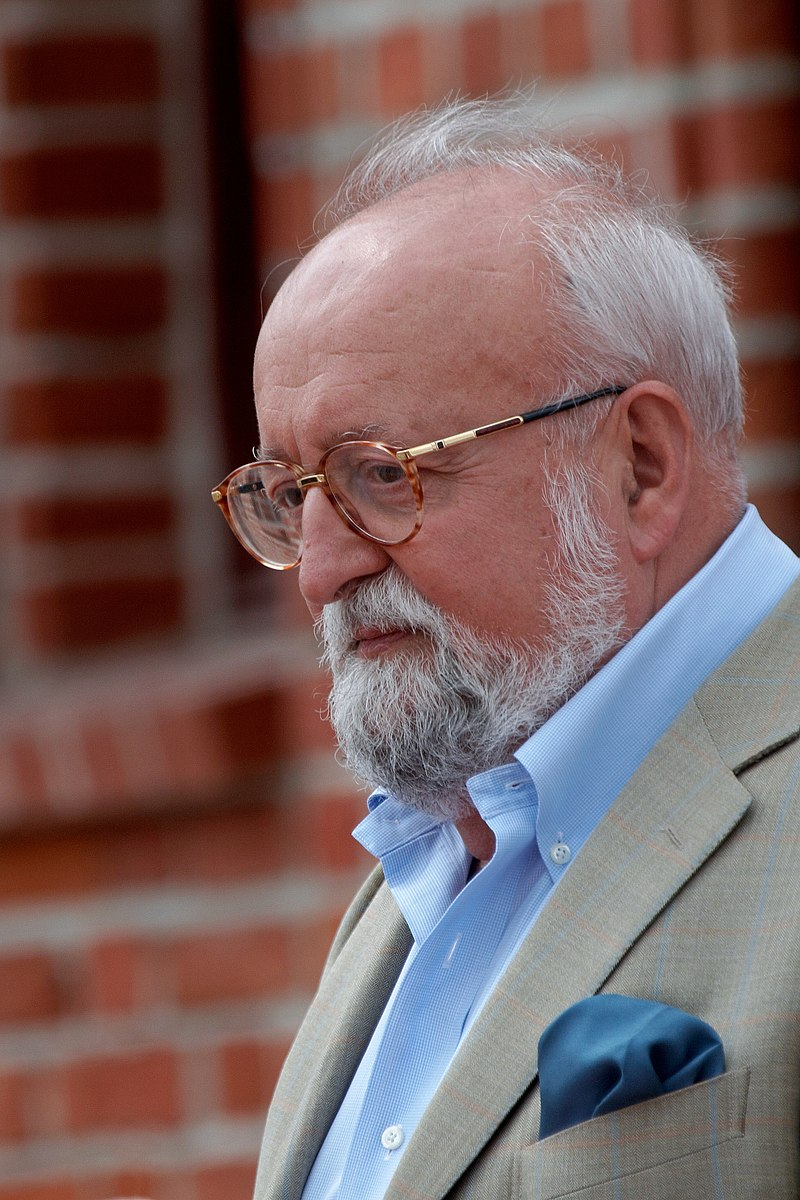

Krzykztof Penderecki (1933-2020)

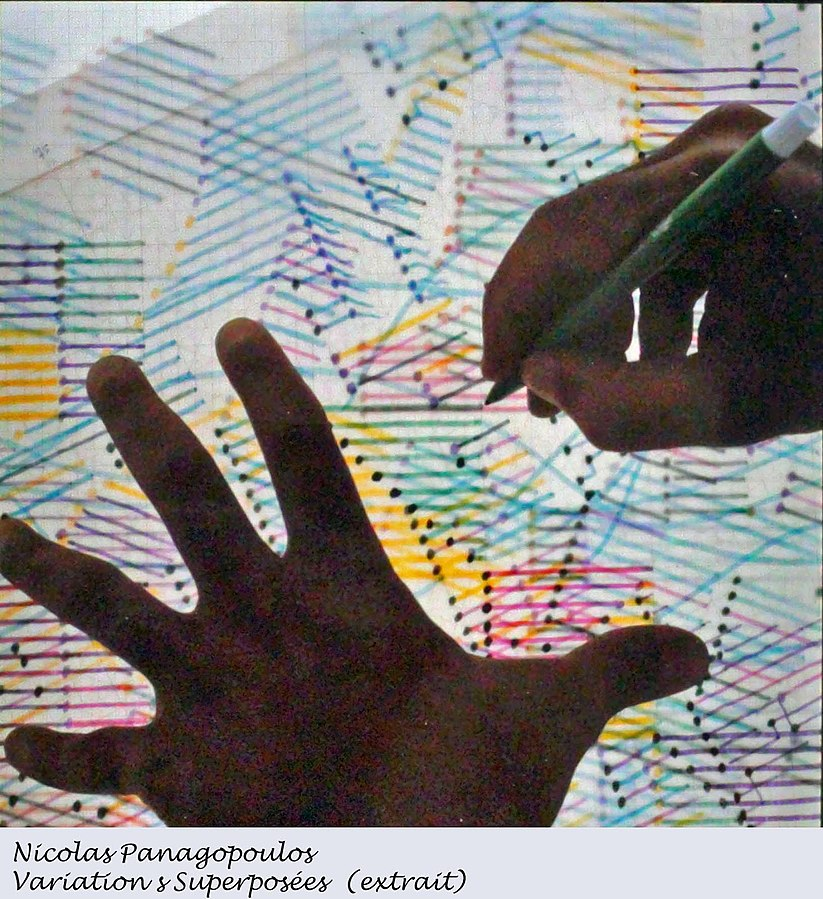

Penderecki was a Polish composer who wrote operas, symphonies, and various choral and orchestral works. Some of his music scores use graphic notation, marking durations with seconds instead of traditional rhythmic notation and indicating directions like playing the highest note possible. He said of his music: “all I’m interested in is liberating sound beyond all tradition.” You can read more about his innovative music notation here:

Graphic Notation of Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima

Bonus Video: Penderecki, Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima

This piece was originally titled 8’37”, as Penderecki’s original intent was to “develop a new musical language,” where timbre and dynamics are of greater importance than melody or rhythm. The music was something abstract for him. However, after hearing it performed, he said “I was struck by the emotional charge of the work…I searched for associations and, in the end, I decided to dedicate it to the Hiroshima victims.”

This video shows Penderecki’s graphic scores that communicate the greater importance of volume, articulation, etc. over melody.

YouTube Video: “Penderecki – Threnody (Animated Score)” by gerubach

Pulitzer Prize in Music

During this time of Postmodernism, one of the most prestigious recognitions in music was the Pulitzer Prize in Music. The original criteria was that it be awarded to “a distinguished musical composition of significant dimension by an American that has had its first performance in the United States during the year.” As recordings have been especially prominent, and live performances less of an assumed occurrence, this was revised to read “for a distinguished musical composition by an American that has had its first performance or recording in the United States during the year.” If you’re interested in exploring notable examples of twentieth and twenty-first-century music, look up and listen to various winners and finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in music.

This text closes with a brief sample of Pulitzer Prize recipients.

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (1939-)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in music. She won for her piece Concerto Grosso 1985, a work that incorporates Baroque and modern musical ideas. She has been described as “one of America’s most frequently played and genuinely popular living composers.”

Credit & License | This work is a copyrighted publicity photograph of a person, product, or event that is known to have come from a press kit or similar source, for the purpose of reuse by the media. It is believed that the use of this photograph to illustrate the person, product, or event in question, in the absence of a free alternative, qualifies as fair use under United States copyright law.

Bonus Video: Zwilich, Concerto Grosso 1985

As you listen to this piece, you’ll hear Baroque ideas: the rhythms are especially regular and consistent, there’s a recurring bass pedal, the bass moves by step, dynamics are terraced, and the instrumentation includes harpsichord. Zwilich also incorporated a melody from Handel’s Violin Sonata in D major. That being said, the melodies and harmonies are far more chromatic, dissonant, and abstract than anything Baroque listeners would have heard.

YouTube Video: “Concerto Grosso 1985: I. Maestoso (Ellen Taaffe Zwilich)” by New World Records / CRi

John Adams (1947-) and Minimalism

Minimalism originated in the 1960s, using a minimal amount of music and repeating it over and over for a hypnotic or trance-like effect. Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass forged this style, and John Adams has been one of the most acclaimed minimalist composers of recent decades.

John Adams grew up in Massachusetts, studied at Harvard, and relocated to San Francisco. He studied twelve-tone serialism but also grew up with rock music.

Bonus Video: Adams, On the Transmigration of Souls

Adams won the Pulitzer Prize for his On the Transmigration of Souls, a piece commemorating those who died in the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

YouTube Video: “On the Transmigration of Souls” by Lorin Maazel – Topic

Bonus Video: Adams, Short Ride in a Fast Machine

This is one of Adams’ most famous works, known for its energy. Note how short motives, comprised of only a few notes, are repeated over and over and over with different instrumentations and alterations. The different melodies from the instruments interconnect like parts of a fast machine.

YouTube Video: “John Adams: Short Ride in a Fast Machine – BBC Proms 2014” by BBC

Caroline Shaw (1982-)

In 2013, Caroline Shaw won the Pulitzer Prize for her Partita for 8 Voices; she was a graduate student at the time and the youngest composer to ever win the award. She originally hoped to be a professional violinist but discovered she could sing exceptionally well and collaborated with a cappella group Roomful of Teeth, the group she sings with and wrote her Partita for.

Bonus Video: Shaw, “Passacaglia,” from Partita for 8 Voices

This work begins with a harmonically straightforward triad but becomes increasingly dissonant as the tone color changes dramatically. It must be noted that it takes extremely talented vocalists to pull off this music.

YouTube Video: “Roomful of Teeth – Shaw: Passacaglia (4th mvt) from Partita for 8 Voices” by CPR Classical

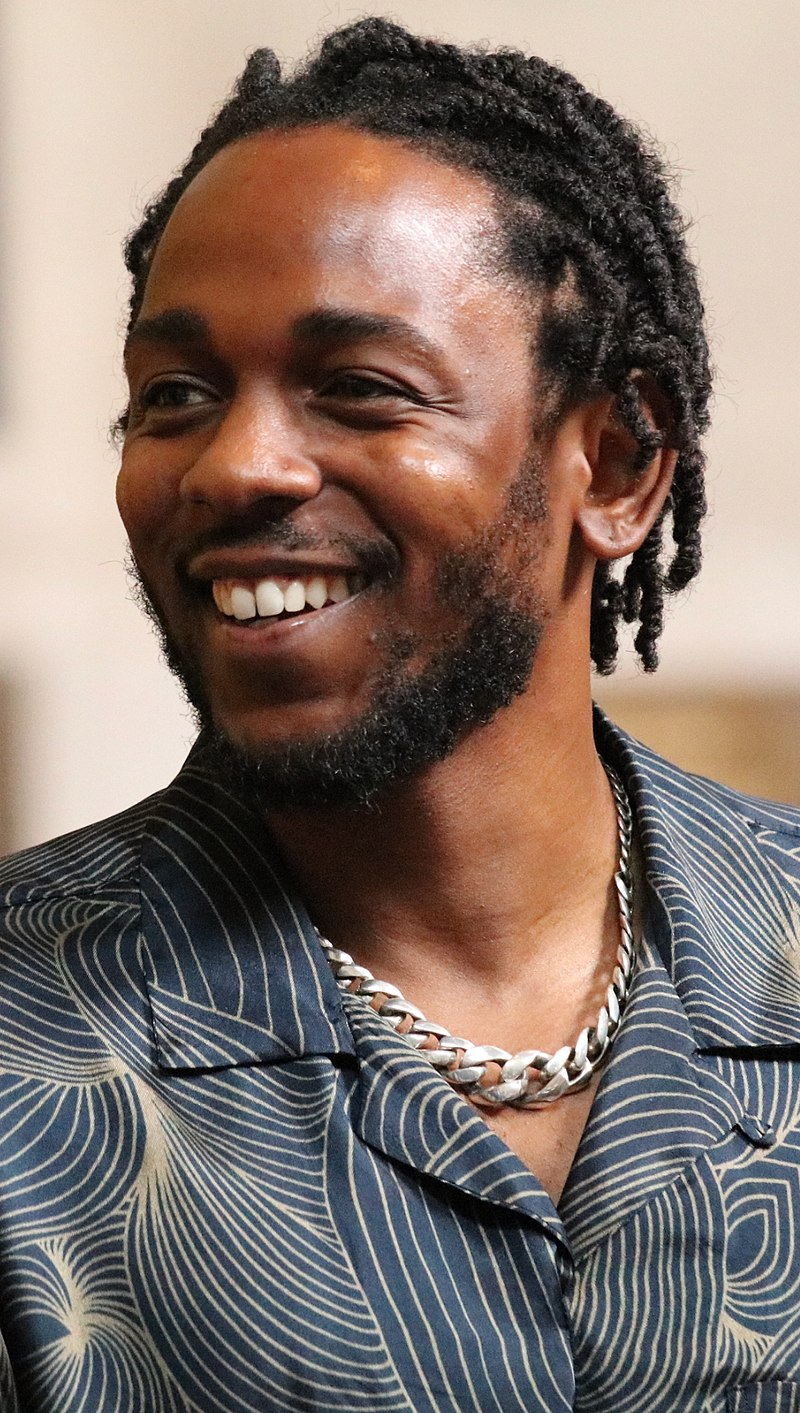

Kendrick Lamar

The vast majority of works to receive a performance have been classical, with a handful of jazz pieces—two genres of “art” music. In 2018, the Pulitzer board shocked the music community by awarding what was almost exclusively a prize for classical music to rapper Kendrick Lamar for his album DAMN. It was already an acclaimed album; it won the Grammy for Best Rap Album and was nominated for their Album of the Year. The song “HUMBLE” from the album won Best Rap Performance, Best Rap Song, and Best Music Video of the Year. The album sold millions of copies. But a rapper had never been a winner or finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in music.

The album was described by the Pulitzer board as “a virtuosic song collection unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African-American life.”

Lamar responded:

“It’s one of those things that should have happened with hip-hop a long time ago. It took a long time for people to embrace us—people outside of our community, our culture—to see this not just as vocal lyrics, but to see that this is really pain, this is really hurt, this is really true stories of our lives on wax. And now, for it to get the recognition that it deserves as a true art form, that’s not only great for myself, but it makes me feel good about hip-hop in general. Writers like Tupac, Jay-Z, Rakim, Eminem, Q-Tip, Big Daddy Kane, Snoop…It lets me know that people are actually listening further than I expected.”

Many in the classical community were excited to see the Pulitzer recognize a wider range of music. Others were vehemently opposed. Some criticized the lyrics as vulgar and misogynistic to women. Some simply didn’t think rap should be considered “high art.” Regardless, it brought more attention and accolades to an already decorated album, and as the Pulitzer board acknowledged, a work that depicts issues of race in the United States.

Bonus Video; Kendrick Lamar, “DNA” from DAMN

In this song, Lamar sings through different points of view to celebrate and criticize Black culture and examine his ancestry and heritage.

Content warning: explicit lyrics

YouTube Video: “Kendrick Lamar – DNA.” by Kendrick Lamar

You can read an analysis of this song at the following link:

Analysis of Kendick Lamar’s DNA

Tania León

Tania León was born in Cuba in 1943; she started studying piano as a four-year-old and pursued bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music. In 1967, she left Cuba and arrived in Miami, Florida as a refugee. She relocated to New York, again studying music at New York University, and became a founding member and music director of Arther Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem. She also worked at the American Composers Orchestra as a Latin American music adviser.

While her music has been performed widely throughout the world, her music wasn’t performed in her native country of Cuba until 2010.

Bonus Video: Tania León, Stride, rehearsal excerpt

The Pulitzer Prize described this piece as “a musical journey full of surprise, with powerful brass and rhythmic motifs that incorporate Black music traditions from the US and the Caribbean into a Western orchestral fabric.”

YouTube Video: “Project 19 in Rehearsal: Tania León’s ‘Stride’” by New York Philharmonic

The following link contains a news report about an interview with Tania León:

The unplanned, unstoppable career of composer Tania León

Conclusion

In this last chapter, we’ve listened to a diversity of sounds. Ellen Taaffe Zwilich’s Concerto Grosso 1985 borrows Baroque melodies and instrumentations with Modernist harmonic ideas. Caroline Shaw’s Partita for 8 Voices draws from medieval chant and Asian singing. John Adams was influenced by rock music. Beyond these amalgamations of diverse sounds, composers like Varèse created new electronic sounds with his audio design for the Philips Pavilion at the Brussels World Fair. Plus, Kenrick Lamar’s rap music was recognized with the Pulitzer Prize in Music. There’s no shortage of variety when studying music today.

This open educational resource is by no means a comprehensive source. There are so many fantastic pieces and composers that couldn’t fit into a single comprehensible document. But we’ve been able to explore a sample of music: a variety of styles to demonstrate the different musical elements, Western classical music, examples of music from around the world, and popular music. As we’ve seen in this chapter, composers of art music have drawn from anything and everything as influences, synthesizing them into a unique voice and creating new sounds altogether.

Now that you’ve finished this text, consider: who are your favorite musicians? Who were their influences? What influenced those influences? And how do those people and their music fit into an appreciation and history of music?

There is a world of phenomenal music. Happy lifelong learning as you continue exploring new musicians and their music.

Attributions

A rejection of traditions and boundaries in art.

Interaction between varied nations and cultures.

Music created by electronic machines, synthesized sounds, computers, etc.

A piano with objects inserted between or on the strings to produce a variety of sounds.

Music with elements not determined until performance.

The use of visual symbols alongside or replacing traditional music notation.

A repetition of short musical ideas and phrases that creates a hypnotic effect.