1 An Introduction to Listening to Music

What is Music?

It might seem like a basic question. We might say that music is something we can hum or dance with, or that we just know it when we hear it. But really, what does it mean? How are we defining music?

Music moves through time; it is not static. When you look at a sculpture or a painting, you take in the artwork—and the different parts of the artwork—at your own pace. You’re in control of how you absorb the work, how quickly you look from one section to another, where your eye moves, and how you connect the different parts of the composition. However, when you listen to music, you’re dependent upon the musician, who controls how quickly or slowly you hear the piece and where the melody goes up and down. In order to appreciate music, we must remember what sounds happened already and anticipate what sounds might come next.

Not all sounds are music. Examples of sounds not typically thought of as music are: alarm sirens, dogs barking, coughing, the rumble of heating and cooling systems, and the like. But, why don’t we think of these noises as music? One might say that these noises lack many of the qualities that we typically associate with music, organization, intent, or expressiveness.

We can define music as the intentional organization of sounds in time. Though not the only way to define music, this definition uses several concepts important to the many understandings of music around the world. “Sounds in time” is the most essential aspect of the definition. Music is distinguished from many other arts by its temporal quality; its sounds unfold over and through time, rather than being absorbed in a single moment.

As humans, we also tend to be interested in music that has a plan, or some kind of intentional organization. Most of us would not associate coughing, sneezing, or unintentionally resting our hands on a keyboard with the creation of music. While we may never know exactly what a songwriter or composer meant by a piece of music, most people think that the sounds of music must show at least a degree of intentional foresight.

We’ll be focusing our studies on music created by humans. Bird calls may sound like music to us, and it’s worth noting that many composers throughout history have been inspired by birdsong. While the songs of animals like birds and whales are fascinating, we’re not as equipped to understand how and why they operate; as such, we’ll limit our music definition to humans.

Let’s take a moment to listen to some music examples:

Ex 1.1: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, first movement

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is his most popular work, and the first movement (even the first seconds) is probably the most recognized piece of classical music. It opens with the famous short-short-short-long motive, about which Beethoven said “There Fate knocks at the door!” This motive appears in different ways throughout the symphony.

Bonus Video: The Beatles, “Yesterday”

“Yesterday” by the Beatles is one of the most critically acclaimed and financially successful recordings of popular music. The song looks back at an ended relationship.

Think about your own favorite music. What do you like about it? Imagine you’re talking with someone who’s never heard this music before. How would you describe how it sounds?

YouTube Video: “Yesterday (Remastered 2009)” by The Beatles

Our Own Music Experience

One common saying is that music is a universal language. Music is heard throughout the world and throughout history. Archeologists have even discovered musical instrumentals that predate recorded history.

You can say that music is universal; anyone can enjoy any style of music.

You can say that music is universal because it exists around the globe and anyone can enjoy any style of music.

At the same time, you can say that music is not universal because not everyone will have the same reaction to or understanding of a piece of music. Think about the music you like now. Did you always like it? How would you have responded to that music five years ago compared to now? Does everyone you know like it?

We all have our own unique experiences that shape our musical preferences. Everyone’s unique personality contributes to their musical tastes; some music you simply like because you like it. But, enculturation—when someone gradually learns a group or culture’s values and practices—and one’s own life experiences both also play a large role. It’s important to know that certain kinds of music in some cultures have very specific functions and connotations that are very different from one simply performing or listening to music.

The more familiar you are with a style of music, the more likely you are to appreciate or enjoy it. Perhaps there are genres or musicians you didn’t initially appreciate or “get,” but after repeated listening and more exposure, they became favorites. Conversely, maybe you once had a favorite song that you grew tired of.

Throughout this text, we hope to expand your musical experiences. You’ll encounter a wide variety of music—much of which you may have never heard before—but you’ll also learn about general characteristics of music that can help you better understand what you already like. We’ll explore a history of Western classical from the Middle Ages (where the largest body of surviving examples begin) to the present. We’ll also spend time exploring music examples from around the world, different forms of popular music, and seeing how different types of music have intersected and influenced each other.

No matter what kind of music you enjoy, you can think about music in terms of rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, tone color, dynamics, and form.

Rhythm

Rhythm organizes music into time as recurring beats. One of the first sounds we ever recognize is our mother’s heartbeat, and rhythm is one of the most powerful elements. A catchy melody might make us sing, but a catchy rhythm will make us move. The majority of music we’ll encounter has a consistent meter (how beats are grouped), usually duple (in two) or triple (in three).

When you think of the word rhythm, the first thing that might pop into your head is a drum beat. But, rhythm goes much deeper than that; it is the way music is organized with respect to time. It works in tandem with melody and harmony to create a feeling of order. Rhythm is the consistent pulse of the music, just like your heartbeat creates a steady, underlying pulse within your body. The beat is what you tap your feet to when you listen to music.

It should be noted that the beat does not measure exact time like the second hand on a clock. Instead, it is a fluid unit that changes depending on the music being played. The speed at which the beat is played is called the tempo.

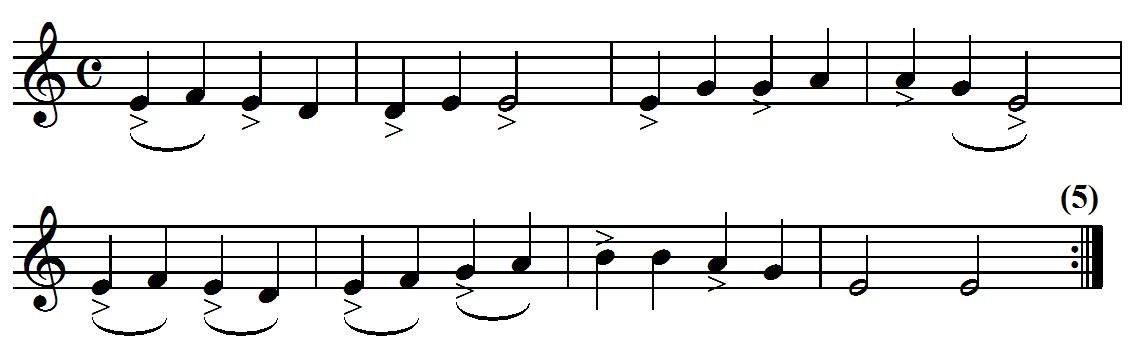

Look at these examples of sheet music; it’s okay if you haven’t read music before. Try to see how the first example has similar rhythms and the second example has more complex rhythms.

As we think about rhythm in a piece of music, and how sounds are arranged, we can ponder: do the notes last for a long time, or do they have short durations? Are the rhythmic patterns simple or complex? Can we count with it? And what about tempo? Is the music slow? Moderate? Fast?

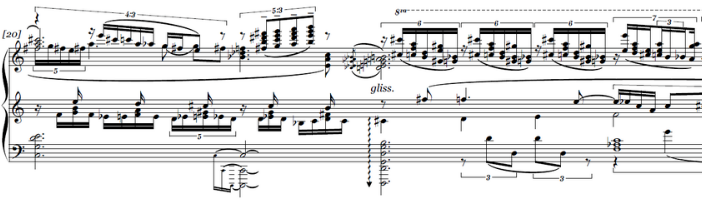

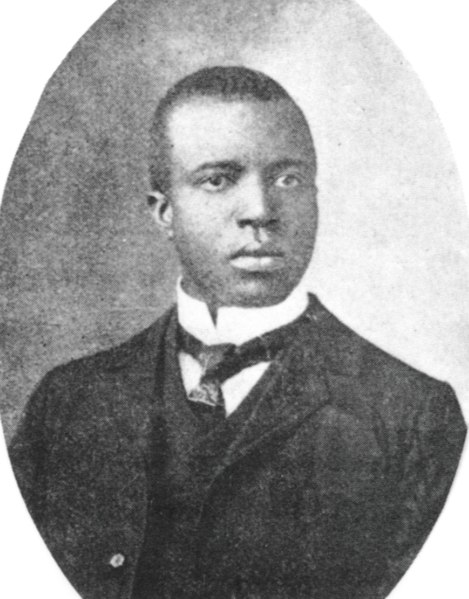

Ex. 1.2: Scott Joplin, The Entertainer

Scott Joplin composed ragtime music, or rags. They were very syncopated and sounded “ragged” or jerky. Syncopation refers to the act of shifting of the normal accent, usually by stressing the normally unaccented weak beats or placing the accent between the beats themselves. Joplin was familiar with the blues, and he combined that sense of syncopation with a European sense of form and harmony, structuring them similarly to military marches.

Melody

Melody is the main line, gesture, or tune that we recognize or sing. The melody of a song is often its most distinctive characteristic. The ancient Greeks believed that melody spoke directly to the emotions.

You can think of melody as a sequence of pitches, or sounds that are recognized as higher or lower than others. In Western music, these have names. On a music staff, they might be labeled A, B, C, etc. They’re often learned by singing syllables like do, re, mi, etc. They can have a wide range or a narrow range. The range of a melody is the distance between its lowest and highest notes. Register is also a concept we discuss in relation to pitch. Melodies can be played at a variety of registers: the low, medium, and high sections of an instrument or vocal range.

Melodies can go up, down, back, and forth. They can move smoothly by single steps or make giant leaps. Notes from melodies are often taken from scales. A tune that moves predominantly by step is a stepwise melody. Such a melody that moves mostly by step, in a smoother manner—perhaps gradually ascending and then gradually descending—might be called conjunct. Other melodies have many larger intervals that we might describe as “skips” or “leaps.” When these leaps are particularly wide and with rapid changes in direction, (that is, the melody ascends and descends and ascends again, and so forth) we say that the melody is disjunct.

Shape is a visual metaphor that we can apply to melodies. As a shape can be considered narrow, wide, short, or long in size, so can a melody. Generally speaking, conjunct melodies have smaller, simpler motions than disjunct melodies.

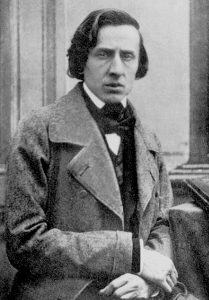

Ex. 1.3: Frédéric Chopin, Prelude in E Minor

As you listen to Chopin’s E minor Prelude, note the repetition in the melody, which barely rises while slowly descending.

Want to learn more about melody? Try to find a video of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts – What is a Melody? In this YouTube video, Leonard Bernstein—one of the greatest American figures in 20th-century music—discusses concepts of melody with classical music examples. It assumes a relatively strong knowledge of classical music, but the information and musical examples are fantastic, and musicians of every level can soak in great information.

Harmony

Harmony occurs when there is more than one pitch at the same time; it is concerned with the different musical sounds that occur in the same moment. This typically involves a main melody with accompaniment. The accompaniment is usually comprised of chords (two or more pitches). Harmony is also related to chords and chord progressions. Harmonies can be consonant (pleasant, stable) or dissonant (harsh, unstable).

Consonant intervals and chords tend to sound pleasant to our ears. They also convey a sense of stability in the music. Dissonant intervals and chords tend to sound harsher to our ears, and often convey a sense of tension or instability. In general, dissonant intervals

and chords tend to resolve to consonant intervals and chords. From the perspective of physics, consonant intervals and chords are simpler than dissonant intervals and chords. However, the fact that many individuals in the Western world hear consonance as sweet and dissonance as harsh probably has as much to do with our musical socialization as with the physical properties of sound. How these sounds are perceived is not universal from culture to culture.

Western music culture has developed a complex system to govern the simultaneous sounding of pitches. Some of its most complex harmonies appear in jazz, while other forms of popular music tend to have fewer and simpler harmonies.

Chord progressions—a repeating series of chords—play an especially prominent role in structuring jazz, rock, and popular music, cueing the listener to the beginnings, middles, and ends of phrases and the song as a whole. Classical music will usually, but not always, use a wider variety of chords.

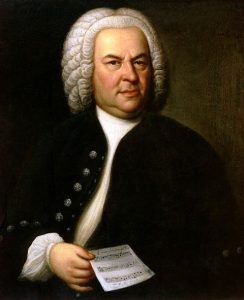

Ex. 1.4: Johann Sebastian Bach, Prelude in C

In this Prelude by Bach, notes of a series of chords are played one after another.

Bonus Video: The Axis of Awesome

Want to learn more about harmony? Harmony relates to chords (a combination of simultaneous notes) and chord progressions (a series of chords). Many popular songs consist of only three or four chords. A viral video by Axis Awesome shows how much mileage popular musicians have gotten out of four common chords:

YouTube Video: “4 Chords | Music Videos | The Axis Of Awesome” by The Axis of Awesome

You can think about our next elements as ways of presenting rhythm, melody, and harmony. For example, you can play the same melody on two different instruments and get two different tone colors – the characteristic sounds from different instruments or voices. Form can be a way of arranging different rhythms, melodies, or harmonies in different ways.

Texture

Texture describes how many different music parts are sounding simultaneously. Monophony, or monophonic texture, is a single melody without any accompaniment. Homophony, or homophonic texture, has a main melody with supporting accompaniment. The accompanying notes are comparatively less involved or complex. Polyphony, or polyphonic texture, features multiple independent melodies—there are many important melodies instead of one main melody.

Ex. 1.5: Japanese shakuhachi performance, Prelude to Kumoi Jishi

This performance on the shakuhachi, a Japanese bamboo flute, is monophonic; there is only one note playing at a time, with no accompaniment.

Ex. 1.6: Bessie Smith, “Lost Your Head Blues”

In this piece with homophonic texture, the piano provides accompaniment that supports the main melodies: the alternating trumpet and vocal parts.

Ex. 1.7: Bayaka women, Congo, polyphonic singing

This example features multiple, interwoven and independent melodies as multiple Bayaka women sing their own, individual parts. In addition to the multiple, independent melodies, percussion—clapping and a rattle—provides accompaniment.

Ex. 1.8: George Frideric Handel, “Hallelujah” Chorus

The “Hallelujah” Chorus from Handel’s Messiah alternates between monophonic, homophonic, and polyphonic textures. This performance was made during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many ensembles created videos featuring musicians performing from their own homes.

Bonus Video: Handel, “Hallelujah” Chorus with Scrolling Bar-Graph Score

You can watch this video of Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus, a song that contains monophonic, homophonic, and polyphonic textures. The different parts are visually color-coded in the video, allowing you to both hear and see how these different textures occur.

YouTube Video: “Handel, Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah (with scrolling bar-graph score)” by smalin

Listening Guide: Handel, “Hallelujah Chorus”

|

Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text |

|---|---|---|

|

0:10 |

Orchestra: Introduces main musical motive in a major key with a homophonic texture where parts of the orchestra play the melody and other voices provide the accompaniment |

|

|

0:17 |

Chorus + orchestra: Here the choir and the orchestra provide the melody and accompaniment of the homophonic texture |

Hallelujah |

|

0:37 |

Chorus + orchestra: Dramatic shift to monophonic with the voices and orchestra performing the same melodic line at the same time. |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

|

0:44 |

Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

Hallelujah |

|

0:49 |

Chorus + orchestra: Monophonic texture, as before. |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth |

|

0:56

|

Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

Hallelujah |

|

1:02 |

Chorus + orchestra: Texture shifts to non-imitative polyphony with the initial entrance of the sopranos, then the tenors, then the altos. |

For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth

|

|

1:31 |

Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

The Kingdom of this world is begun |

|

1:57 |

Chorus + orchestra: Imitative polyphony starts in basses, then is passed to tenors, then to the altos, and then to the sopranos. |

And he shall reign for ever and ever

|

|

2:21

|

Chorus + orchestra: Monophonic texture, as before. |

King of Kings |

|

2:24 |

Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture, as before. |

Forever, and ever hallelujah hallelujah |

|

2:28 |

Chorus + orchestra: Each entrance is sequenced higher; the women sing the monophonic repeated melody motive; Monophony alternating with homophony |

And Lord of Lords…Repeated alternation of the monophonic “King of kings” and “Lord of lords” with homophonic “forever and ever” |

|

3:02 |

Chorus + orchestra: Homophonic texture |

King of kings and Lord of lords |

|

3:08 |

Chorus + orchestra: Polyphonic texture (with some imitation) |

And he shall reign for ever and ever |

|

3:20 |

Chorus + orchestra: The alternation of monophonic and homophonic textures. |

King of kings and Lord of lords alternating with “for ever and ever” |

|

3:31 |

Chorus + orchestra: Mostly homophonic |

And he shall reign…Hallelujah |

Tone Color

In this course, color refers to the unique sounds, or timbres, of different instruments and voices. For example, a violin and an electric guitar have very different sounds, even when they play the same pitches. We can associate this tone color with different instruments and voice types. There are four main voice types. From high to low, they are soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. In classical music, the main families of instruments—groups of instruments with similar colors—are string, woodwind, brass, and percussion.

We can use a wide variety of descriptive terms to describe the tone color, or quality of the sound. A trumpet ensemble might sound bright and majestic. A choir might sound lush and peaceful. Heavy metal drums might sound cutting, harsh, or dry. It’s important to remember that color describes the sound, not necessarily the mood of the music. However, the same descriptive words can often apply to both sound and mood, depending on the piece of music.

Ex. 1.9: Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, “Gut Bucket Blues”

This early jazz piece by Louis Armstrong features distinctive tone color from a variety of instruments: the twangy banjo that opens the piece, Louis Armstrong’s characteristic voice that seems to sound like both gravel and syrup, the piercing cornet and clarinet melodies, the smooth sounds of the trombone, and the twinkling of the piano keys in the middle.

Dynamics

Dynamics is a term that describes volume. This is a fairly straightforward concept, as many have experienced adjusting the volume on a computer or stereo. A piece of music might be loud or soft. The volume might stay consistent, or it might change—gradually or suddenly and dramatically—throughout the music.

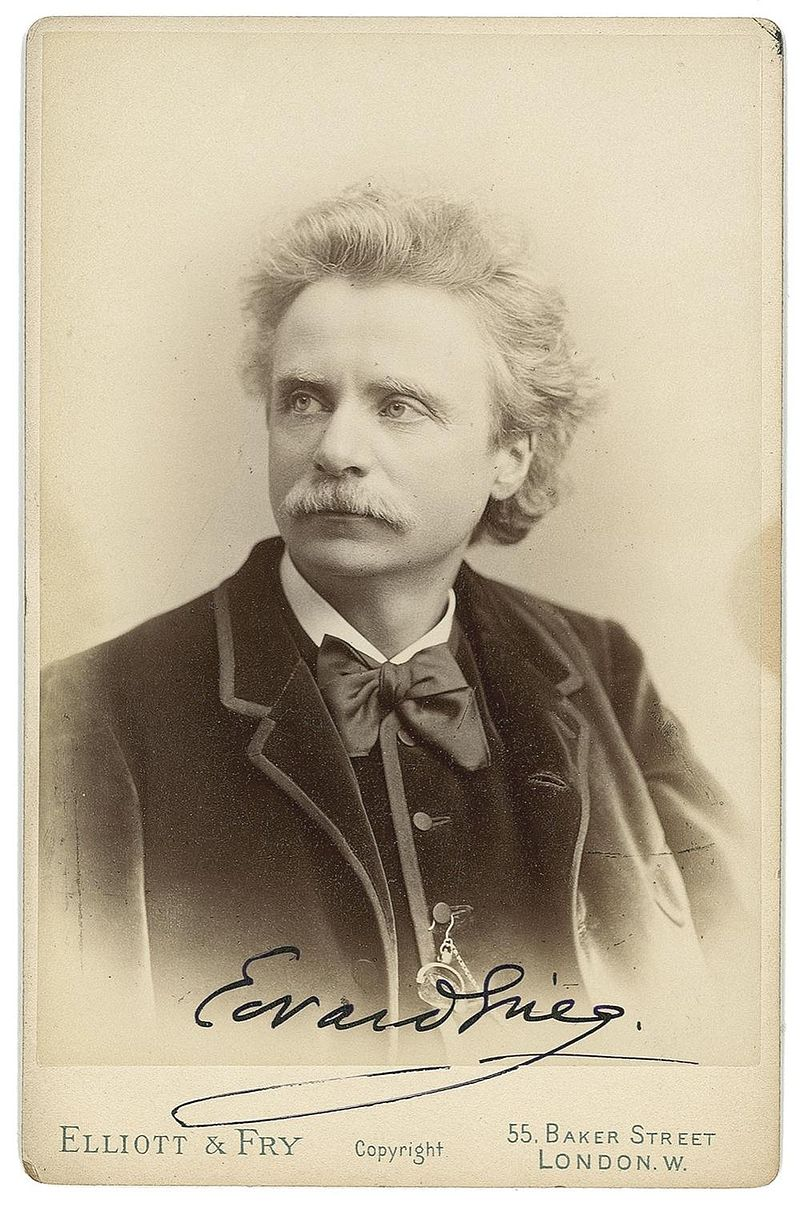

Ex. 1.10: Edvard Grieg, “In the Hall of the Mountain King”

The piece starts quiet, but it becomes louder and louder, increasing in drama and excitement.

Form

Form is the arrangement of parts in a song or a piece of music. There are four ways to present ideas to create form: statement, which presents a musical idea; repetition, which repeats the idea; contrast, which presents a new idea; and variation, which takes already introduced ideas and alters them. In popular music, a common form is verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus.

There are many possible forms a piece of music might use. Binary form has two main parts: A and B. Ternary form has three main parts: A, B, and return to A. We’ll discover different forms of music as we go through the course.

Ex. 1.11: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Variations on “Ah! Vous Dirai-Je, Maman” (“Twinkle” Variations)

One example of a form from classical music is theme and variations. In this theme and variations, Mozart introduces a theme and presents several variations. The same melody is present each time, but the accompaniment changes.

Bonus Video: Super Mario World

Want to learn about Theme and Variations and Video Game Music? Check out the soundtrack to Nintendo’s 1990 video game Super Mario World, created by Koji Kondo. “Overworld,” “Underground,” “Underwater,” “Bonus Level,” “Athletic,” “Ghost House,” and “Castle,” all use the same melody but vary from track to track.

YouTube Video: “Super mario world ost full soundtrack” by MusicGamesOnly

Summary

We all have our different musical tastes, preferences, and experiences. No matter what kind of music you like, you can think about it in terms of rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, tone color, dynamics, and form. What are you hearing that you like? Try to identify what you like about the music that you enjoy. It’s difficult to put musical preferences into words, but the more you do it, the easier it gets. No matter how long you have (or have not) studied music, you can think about these concepts to appreciate and understand music.

In our next chapter, we’ll look at music examples from the Middle Ages and Renaissance, some of the largest and earliest collections of preserved music in history. There was certainly plenty of music happening before those times, but not as many examples have survived.

Attributions

Sound and silence organized in time.

The gradual learning of a group or culture’s values and practices.

The way the music is organized in respect to time.

The speed at which the beat is played.

The act of disrupting the normal pattern of accents in a piece of music by emphasizing what would normally be weak beats.

A succession of notes in musical phrases or compositions.

The low, medium, and high sections of an instrument or vocal range.

A series of pitches, ordered by the interval between its notes.

A melody that moves mostly by step, in a smooth manner.

The distance in pitch between any two notes.

A melody that jumps, with larger intervals between notes.

Any simultaneous combination of tones and the rules governing those combinations.

The simultaneous sounding of three or more pitches. Like intervals, chords can be consonant or dissonant.

A repeating series of chords.

A term used to describe intervals and chords that tend to sound sweet and pleasing to our ears. Consonance, as opposed to dissonance, is stable and needs no resolution.

Intervals and chords that tend to sound harsh to our ears. Dissonance is often used to create tension and instability, and the interplay between dissonance and consonance provides a sense of harmonic and melodic motion in music.

The ways in which musical lines of a musical piece interact.

Musical texture comprised of one melodic line. A melodic line may be sung or played by one person or 100 people.

Music where the melody is supported by a chordal accompaniment that moves in the same rhythm. Homophony is generally the opposite of polyphony where the voices imitate and weave with each other.

Musical texture that simultaneously features two or more relatively independent and important melodic lines.

The tone color or tone quality of a sound.

The variation in the volume of musical sound.

The structure of the phrases and sections within a musical composition.

The presentation of a theme and then variations upon it. The theme may be illustrated as A, with any number of variations following it – A’, A’’, A’’’, A’’’’, etc.