7 Modernism

A New Diversity of Styles

In Chapters 5 and 6, we saw a wide variety of new music styles and philosophies emerge. But even with new ideas—program music, Nationalism, and a host of opera styles—the majority of the music was shaped by singable melodies. As the twentieth century approached, musicians sought to be more modern than ever before and, in so doing, questioned the very foundations basic to the music of the previous two centuries.

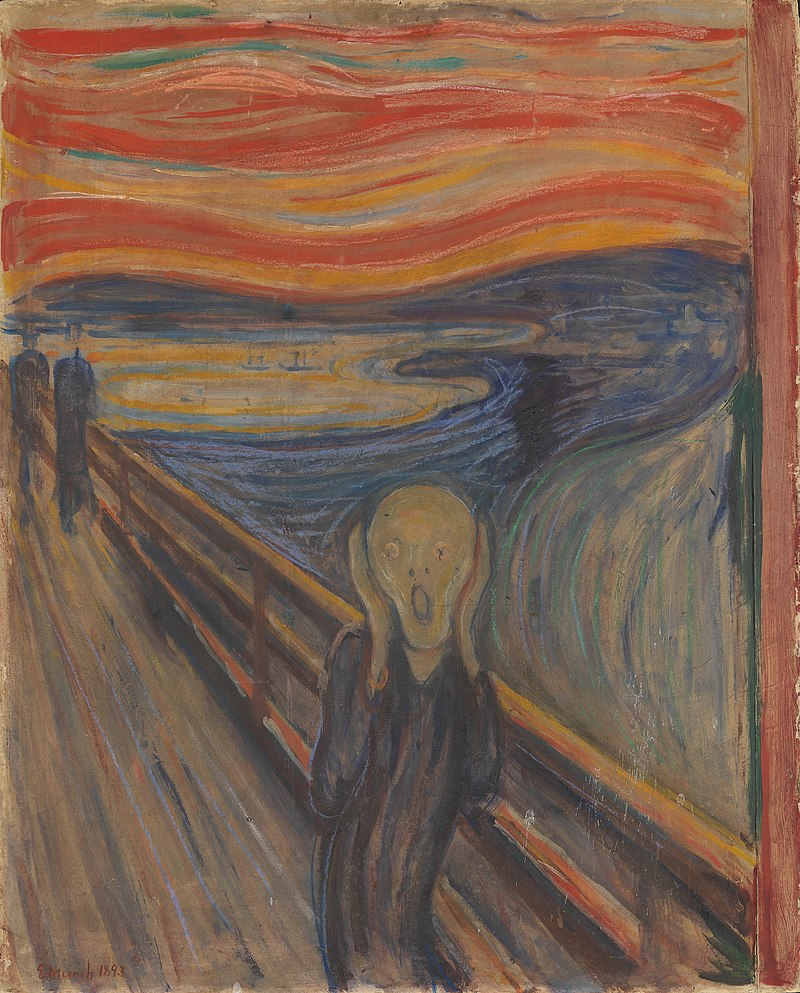

Remember how the Romantic era saw an increase in chromaticism, using lots of pitches that didn’t belong to the key the piece was in? By the end of the nineteenth century, composers were using so many notes from outside the traditional scales that they more or less broke tonality. Additionally, they were also influenced by artwork of the time that was becoming less representational and more abstract. Impressionism, Cubism, and Expressionism each had a significant influence on the composers of this chapter. Just like Modern Art, some of these listening examples can be a little difficult to approach, but the more you listen, the more familiar these pieces will become, and the more sense they’ll make.

Modernism is a somewhat odd term for those living after the fact. After all, we so often associate the term “modern” with “contemporary”—it’s new and recent, and the artistic trend of Modernism is over a century old; the examples in this unit were composed from the late-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century. Instead, Modernism can be thought of as embracing new ways of art, and new conceptions of what constituted the various elements of music. It was a reaction against the beauty of Romanticism, particularly after the horror of World War I. This artistic movement jarred many audiences in the early twentieth century. In Vienna, crowds booed Arnold Schoenberg’s dissonance. In Paris, audiences rioted at the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring). These composers were also involved in modern visual arts: Debussy interacted with Parisian writers and artists, Stravinsky collaborated with Picasso—the Cubist painter who visually broke down images into different shapes and dimensions—and Schoenberg exhibited his art alongside expressionist Kandinsky.

Music, like the other arts, does not occur in a vacuum. Changes brought on by advances in science, and inventions resulting from these advances, affected composers, artists, dancers, poets, writers, and many others at the turn of the twentieth century. Modernism was a movement where artists, musicians, philosophers, etc., felt that traditional forms were no longer adequate to express their ideas. In general, art became more non-representational, abstract, angular, and harsh. Musicians grew less interested in established forms and harmonies as composers like Debussy, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Ives, and Copland created their own musical styles.

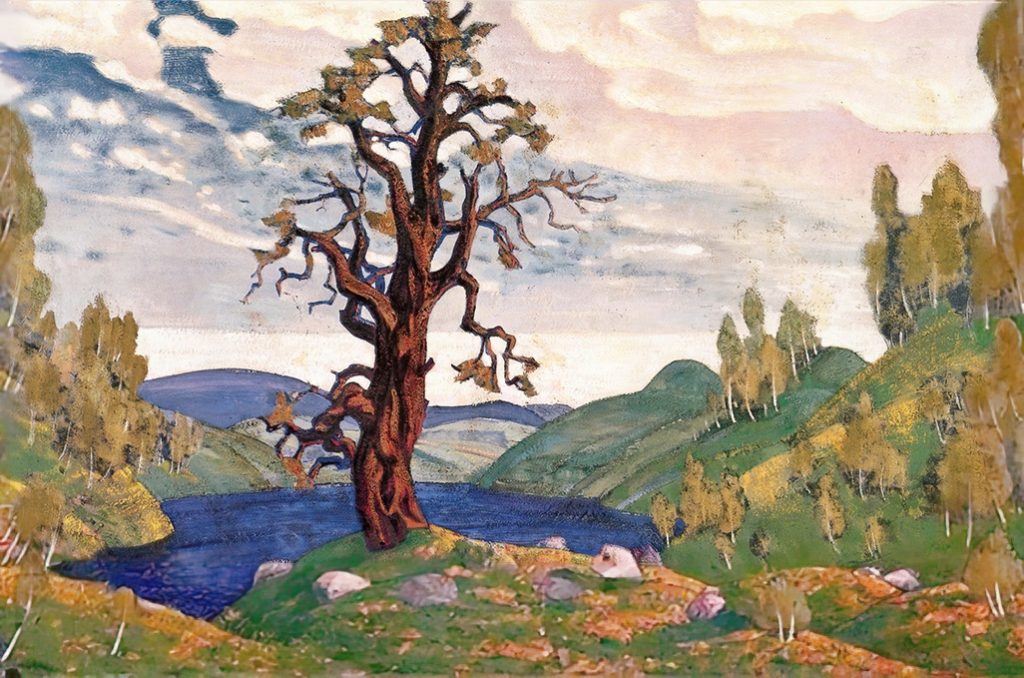

As you go through this section, look up more images of Impressionist (figure 7.1), Cubist (figure 7.2), and Expressionist (figure 7.3) art. How do these relate to the sounds you’re hearing in the Listening Examples?

For many composers, the raw emotion and sentimentality reflected in the music of the nineteenth century had grown tiresome, and so they began an attempt to push the musical language into new areas. Sometimes, this meant bending long-established musical rules to their very limits, and, in some cases, breaking them altogether. One of the by-products of this urgency was fragmentation. As composers rushed to find new ways of expressing themselves, different musical camps emerged, each with their own unique musical philosophies. Melodies became angular, where some pitches in the melody might be an octave higher or lower than adjacent pitches. Heavy chromaticism obscured a sense of tonic. Schoenberg referred to an “emancipation of dissonance;” while past generations of composers used dissonance to resolve to consonance, Modern composers explored dissonant chords and intervals as their own independent sound. Some, like Charles Ives, even used tone clusters; while the notes of a triad are a third (three or four half-steps) apart, tone clusters sound like a cluster of adjacent notes.

It’s worth noting that the gargantuan ensembles of the Romantic symphony gave way to smaller ensembles. It was difficult to budget for large ensembles after the destruction of World War I, particularly with musical styles that weren’t as immediately accessible.

Occasionally, it’s relatively easy for historians to agree when a period or style begins or ends. For example, the Baroque period is generally agreed to have started in 1600, around the beginning of opera, and ended in 1750 with the death of Bach. The turning of the Classical period to the Romantic is a little less clear cut, but as Beethoven serves as a bridge from one period to the next, one can date that division around his pivotal works. Such distinctions blur with Modernism (this Chapter) and Postmodernism (Chapter 10). Modernism ideas appeared in the late nineteenth-century works of Debussy, but Gustav Mahler composed his Romantic symphonies well into the first decade of the twentieth century.

Impressionism in Painting and Music

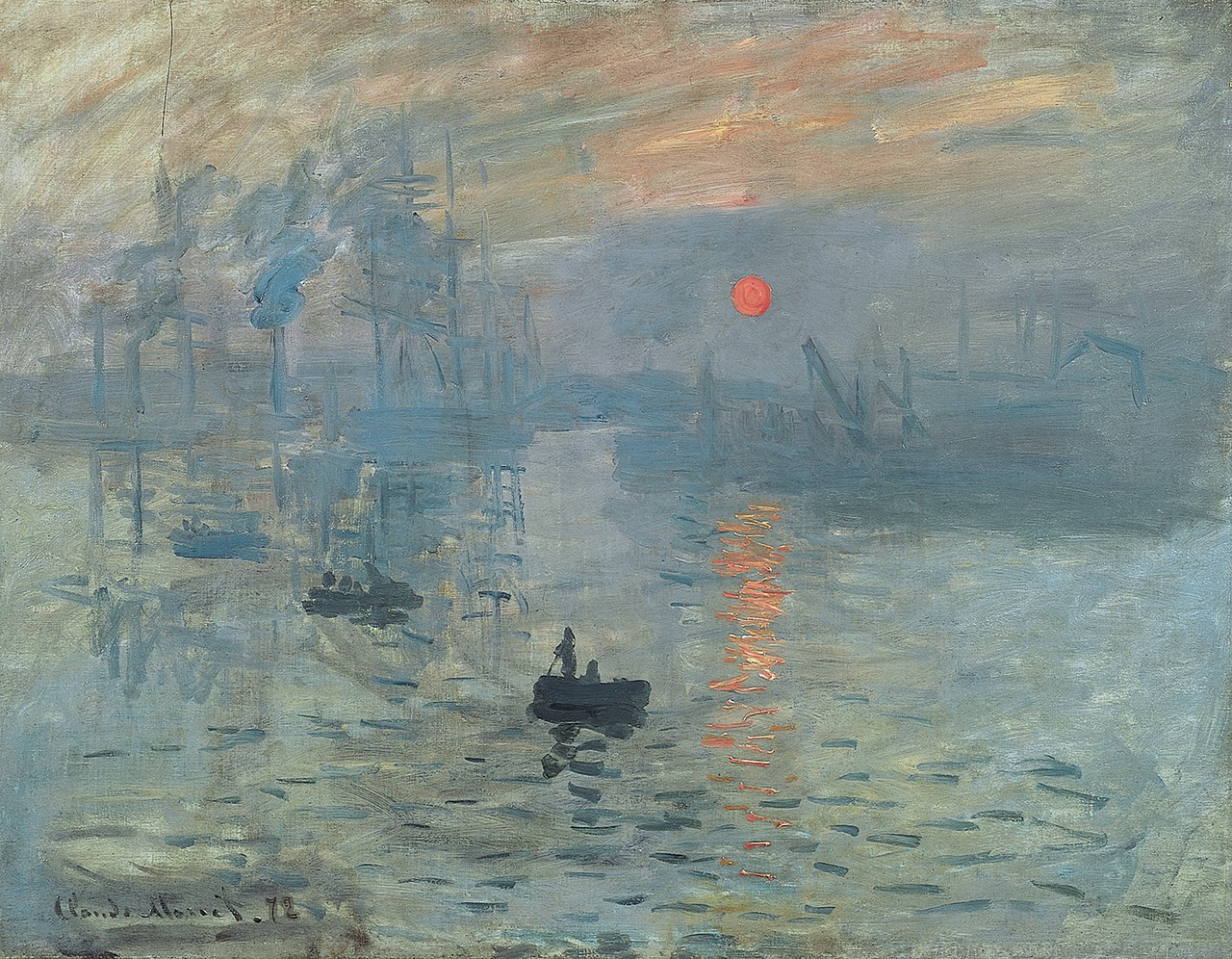

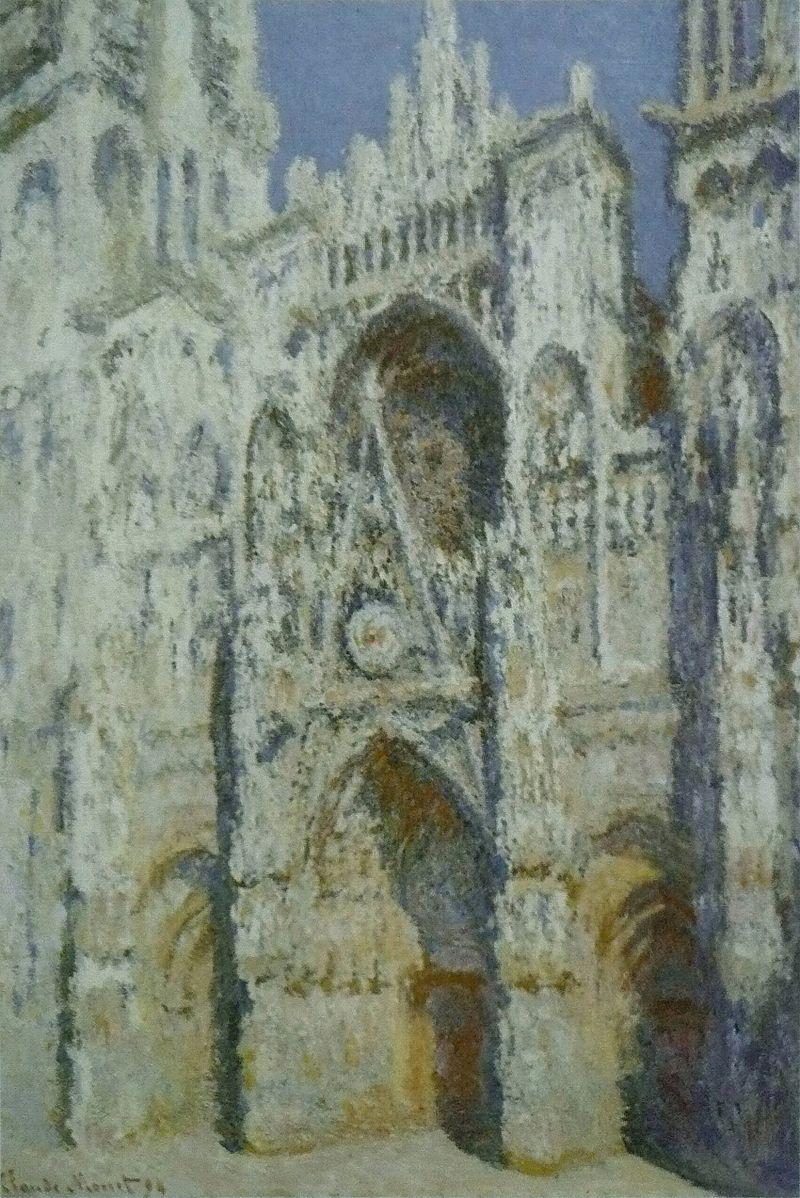

Various French composers were drawn to the works of Impressionist visual artists like Monet (figure 7.1) and Degas, artists who suggested or implied images rather than photorealistically depicting them. They created open compositions and emphasized the effects of light and movement. Critics called these artists “impressionists,” as if the works looked incomplete and gave merely an impression of what they were painting.

Composers like Claude Debussy musically emulated these ideas of Impressionism. Debussy once said “You do me a great honor by calling me a pupil of Claude Monet,” and borrowed titles like “Images” or “Sketches” for his works.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Debussy came from a non-musical family near Paris; it was a surprise that he became a prodigy, enrolling in the Paris Conservatory at ten years old. He found work as a performer which brought him to various parts of Europe. He won the Prix de Rome, a prize involving a three-year residency in Rome, but he preferred Parisian life. He stayed in Paris for the remainder of his life after his Rome residency ended. His first masterpiece—and an orchestral favorite today—was Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun).

Ex. 7.1: Claude Debussy, Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun

This prelude was written to be performed before a reading of a poem of the same name, written by Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé. Symbolists were less interested in the literal meaning of a word than its sound. The mythological faun or satyr (half man, half goat) pursued nymphs of the forest, and the poem and music depict him wistfully resting in the forest. While program music composers like Berlioz created a musical narrative, Debussy said, “My Prelude is really a sequence of mood paintings, throughout which the desire and dreams of the Faun move in the heat of the midday sun.”

For previous orchestral composers, instruments were a way to introduce new melodies. For Debussy, instruments were a way to color his work. The different sounds, timbres, and orchestral colors in his music are almost more important than the melodies, chords, and rhythms.

Ex. 7.2: Claude Debussy, The Sunken Cathedral

Debussy also sought to musically create images at the piano. But, while he could use the different instruments of the orchestra to paint different tone colors, the sounds of the piano are generally monochromatic. Debussy used extremes in pitch—very low and very high notes—to help paint the image of a cathedral rising from the sea and becoming visible. He used harmonies reminiscent of ancient chant and the intervals of church bells to create an image of the church with music as his paintbrush.

Bonus Video: Debussy, Clair de lune

To hear Debussy’s most famous piano composition and see graphic representation of the music, watch the below video.

YouTube Video: “Debussy, Clair de lune” by smalin

Exoticism in Music

Paris was very interested in the sights and sounds of the Eastern world at the end of the nineteenth century. It hosted a World’s Fair in 1889, which introduced Debussy to Cambodian, Vietnamese, and Indonesian music. He was especially struck by Indonesian gamelan music (which we’ll explore in Unit 8), and said, “Do you not remember the Javanese [Indonesian] music that was capable of expressing every nuance of meaning, even unmentionable shades, and makes our tonic and dominant sounds seem weak and empty?”

As the twentieth century approached, composers explored exoticism, using sounds heard beyond the Western European tradition and evoking or incorporating non-Western scales, rhythms, and instruments. It’s worth noting that many composers were simply conveying something that was designed to sound foreign, rather than accurate depictions of other music cultures.

The Exotic of Spain: Ravel’s Boléro (1928)

Maurice Ravel, who wrote a famous orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, found Spain to be inspiring; its proximity to Africa and the hybridization of many cultures (the city of Cordoba was at one point home to Christians, Jews, and Muslims) fostered inspiration in many artists.

One of the works from the last decade of Ravel’s life was music for a ballet, Boléro (named for the genre “bolero,” a slow Spanish dance with guitar and castanet accompaniment).

Bonus Video: Ravel, Boléro

Boléro is marked with a distinctive rhythmic ostinato on the snare drum. In some ways, the piece is relatively static. Its form repeats an A and B section over the course of fifteen minutes. Instead of different themes and key centers, Ravel used different instrumentations and dynamics to propel the piece.

YouTube Video: “Ravel: Boléro – BBC Proms 2014” by BBC

A fun fact for video game enthusiasts: Nintendo’s original The Legend of Zelda was going to use an 8-bit version of Boléro in its title screen, but later learned they legally couldn’t due to copyright restrictions. You can find various fan-made 8-bit versions to accompany the game on YouTube.

Lili Boulanger

Marie-Juliette Olga (Lili) Boulanger was born in Paris to a Russian princess and Parisian music teacher. She showed impressive musical talent at a young age. The French composer and family friend Gabriel Fauré recognized that the two-year-old Lili had perfect pitch. Unfortunately, that same year she became sick and had a weak immune system for the rest of her life. She died at the age of 24, just a few years after becoming the first woman to win the prestigious Prix de Rome composition prize.

Lili Boulanger was influenced by the music of Debussy. Her sister, Nadia Boulanger, was one of the most influential music teachers of the twentieth century who taught students including prominent composers Aaron Copland and Philip Glass.

Ex. 7.3: Lili Boulanger, Nocturne for flute and piano

This piece was originally written for piano and violin, and is often performed by flute instead of violin. The piece opens with twinkling sparkles from the piano. The piano provides a light accompaniment, letting the listener focus on the melancholic melody of the flute/violin.

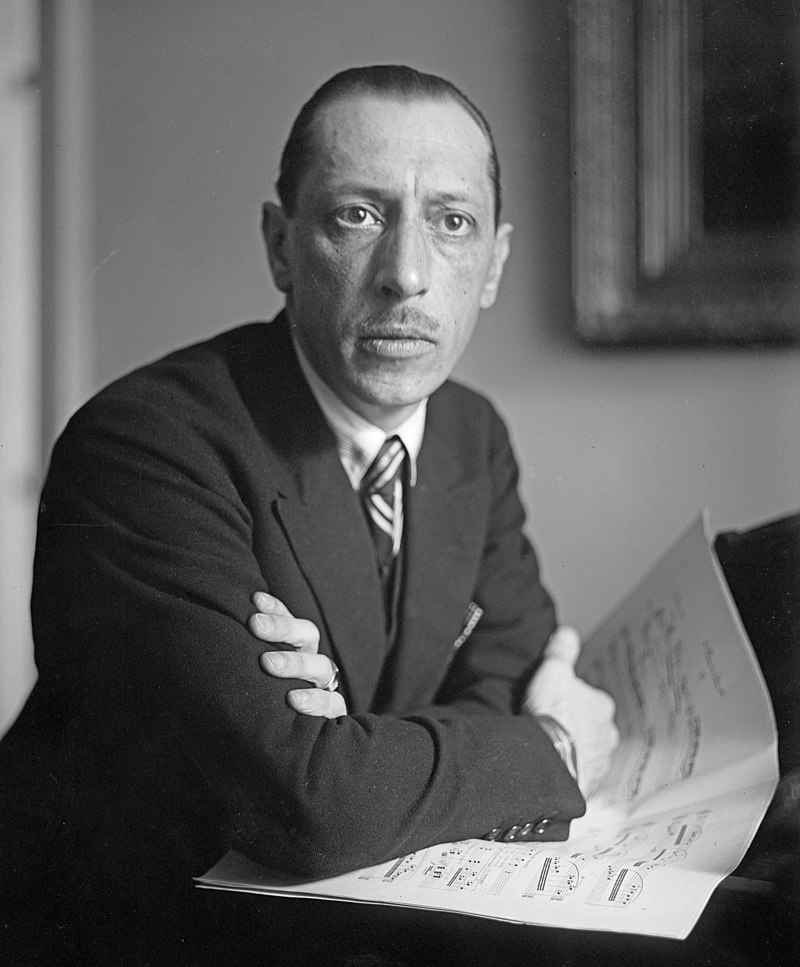

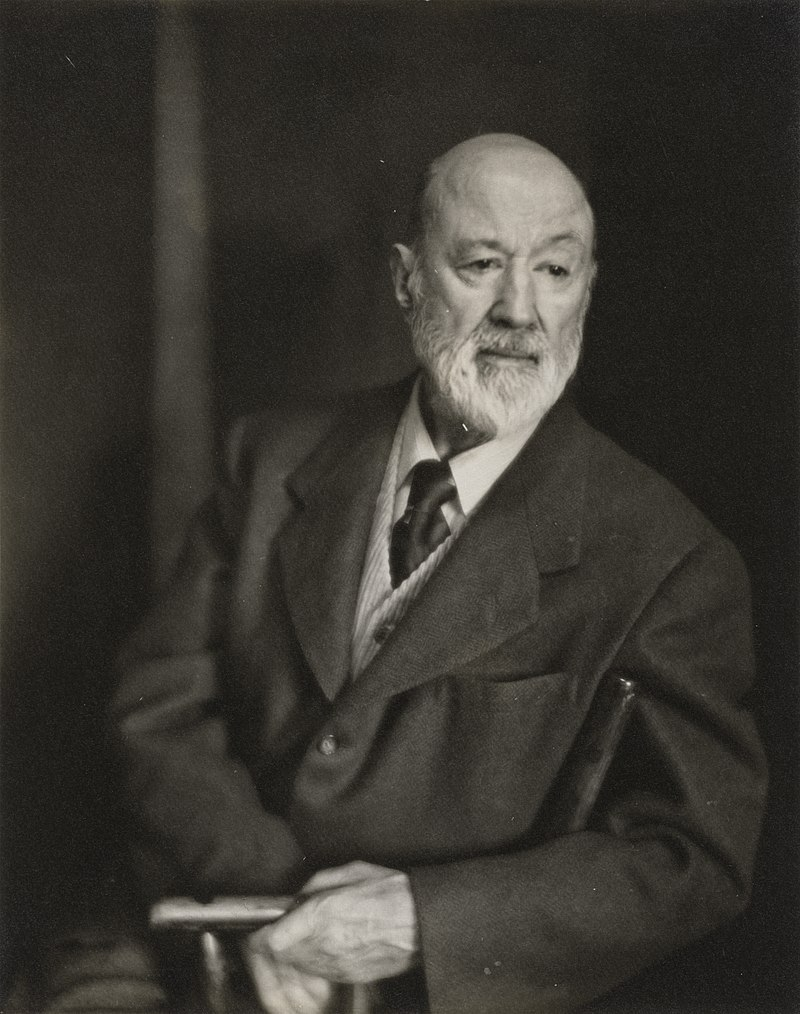

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

Stravinsky was one of the most celebrated, notorious, and influential composers of the twentieth century. During the height of the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union honored him for his eightieth birthday in the White House and Kremlin, respectively. He rose to fame as the principal composer of the Ballets Russes (Russian Ballets) and eventually relocated to Los Angeles. Throughout his career, he worked through a variety of musical styles.

World War I temporarily ended the large-scale symphony orchestra heard in the Romantic Period; between the war and the recovery from it, ensembles of that time weren’t financially feasible. Composers like Stravinsky wrote in a Neoclassical style, using traditional forms for the leaner ensembles of the Baroque and Classical periods. Stravinsky highlighted the bright winds and percussion over the strings in his writing and wrote rhythmically complex music.

Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913)

The Rite of Spring is a work of Primitivism. It tells the story of an ancient, pagan people who celebrate spring and the Earth by sacrificing a girl who dances to death. The accompanying ballet was not what we normally think of, with tutus and graceful movements. Instead, the gestures are jerky and the original costumes looked like primitive attire. The melodies slither and the rhythms pound. While the work today is recognized as a landmark of the twentieth century, the audience at its premiere—who had never witnessed anything like this—reacted in chaos.

Bonus Video: Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, Introduction and Act I

This video reenacts the original choreography and costumes starting at 2’43.” Between the ever-shifting meter, the melodies that are both bizarre and folk-like, and dissonant harmonies, The Rite of Spring was nothing short of groundbreaking.

YouTube Video: “Rite of Spring – Joffrey Ballet 1987” by Uncle Waldemar

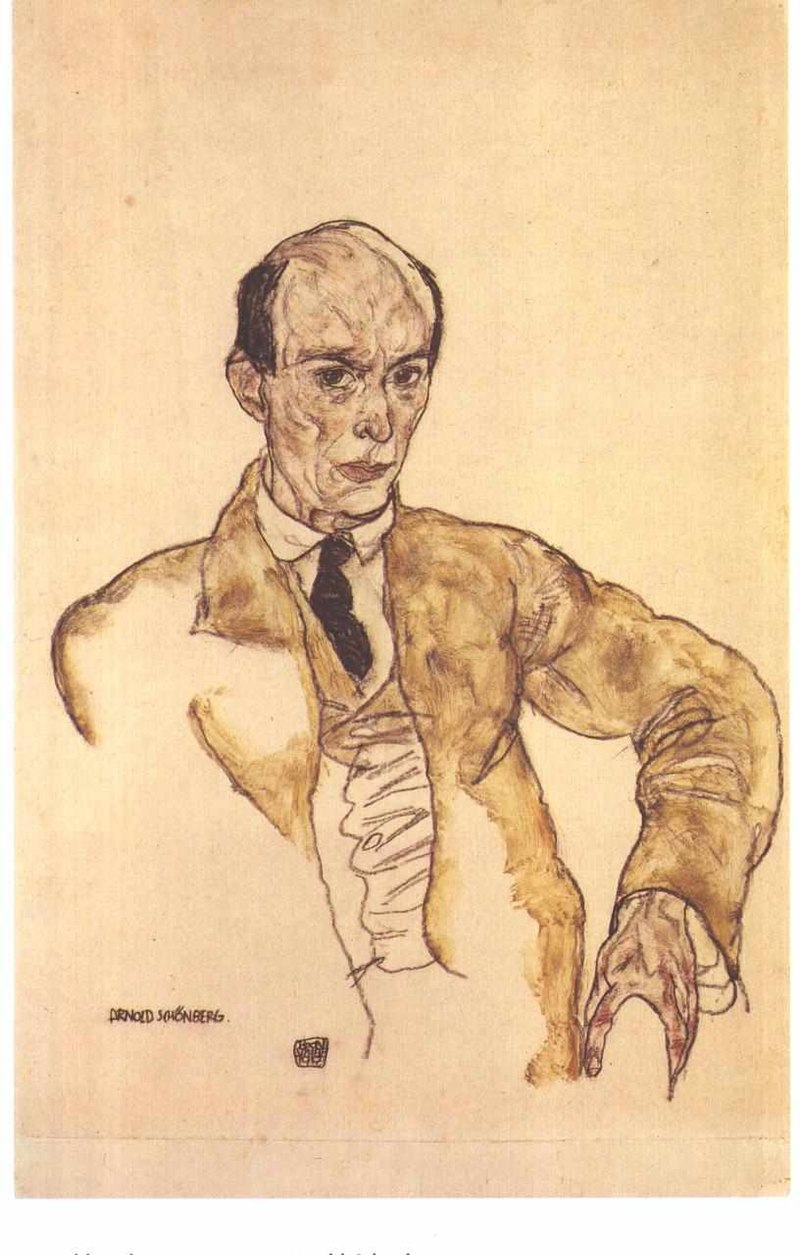

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

On the other side of Europe, in Vienna, Arnold Schoenberg created his own brand of Modernism. He and his students, Alban Berg and Anton Webern, formed the Second Viennese School (the first being Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven). He came from a modest Jewish family and taught himself music by studying Wagner, Brahms, and Mahler. His pieces were performed in Vienna, but usually to a poor reception. He was especially influenced by the harmonic language of Wagner, which could be tonally ambiguous. He pushed that ambiguity to the point of writing music without a tonal center. Audiences were bewildered, and at one concert, the police were called to control the audience.

Pierrot lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot, 1912)

Schoenberg’s best-known work is the expressionist Pierrot lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot), written for a small ensemble and female singer. The core ensemble—flute, clarinet, violin, cello, and piano—can create a vivid variety of colors. The instrumentation was influential, and is now called a Pierrot ensemble.

Pierrot lunaire sets twenty-one expressionist poems about Pierrot, dangerously affected by the moon, expressing his anxieties through Sprechstimme (German for “speech-voice”), a technique that combines talking with singing.

Ex. 7.4: Arnold Schoenberg, Pierrot lunaire, “Mondestrunken” (“Drunk with Moonlight”)

The work opens from the poet’s perspective. He sets the scene. Pierrot is heard in the music, though not yet mentioned by name. We hear the moonlight painted by the instruments.

Twelve-Tone Music

Schoenberg wanted to create music without a tonal center, but he also wanted a means of cohesion—a sense of order in his music. Twelve-tone music was his eventual solution; he ordered all twelve notes of the chromatic scale and used this ordering of notes to create melodies and accompaniments. He used counterpoint, used by past masters like Bach and Josquin, to create variations of this order, turning his sequence of pitches upside-down and/or in reverse.

Bonus Video: Anton Webern, Variations for piano, opus 27 no. 2

Anton Webern was a student of Arnold Schoenberg. This visual representation of the music helps show the piece’s tight organization of using the same-sized pitch intervals around a central pitch. This is admittedly a very unfamiliar style of music. It might help to think of pieces like these, with their tight-knit structure but abstract sounds, like miniature musical crystals or geometric patterns.

YouTube Video: “Webern, Variations for piano, opus 27 no. 2” by smalin

American Modernism

The United States has been a diverse mixture of different peoples and cultures. Musically, American-born musical styles include gospel, blues, ragtime, jazz, rock and roll, hip-hop, Appalachian bluegrass, zydeco, and country and western. This diversity of styles is also seen in American art music.

Charles Ives (1874-1954)

Charles Ives was born in New England to a Union army bandleader. The senior Ives gave his son quite the music education, including traditional studies of counterpoint, various instruments, the works of the European masters, and even exposure to polytonality—music that is simultaneously in different keys.

Ives pursued a career in insurance instead of music; he knew the music he loved to create didn’t have widespread appeal. By day, he was a successful businessman. By night, he composed. He created a large body of work and didn’t bother sharing it with performers or audiences until decades afterward. Independent of the music world at large, he incorporated atonality and polymeter before Schoenberg and Stravinsky. No composer prior to him extensively used polytonality, and he also experimented with microtonality, using pitches that sound between the pitches of the piano. But he also included popular songs, and created a collage of simple or familiar melodies with unconventional techniques.

Bonus Video: Ives, The Unanswered Question

Ives uses a “collage” technique, rearranging three different layers of music. Ives also gave descriptive associations to these layers: 1) the quiet, subdued, and beautiful strings, “The Silences of the Druids―Who Know, See and Hear Nothing;” 2) a solo trumpet, asking “The Perennial Question of Existence” with its tonally ambiguous melodies; 3) the woodwinds, or the “Fighting Answerers.” Throughout the piece, the woodwinds “answer” the trumpet with frantic, disjointed melodies. The trumpet’s final melody, or “question,” is answered by silence.

YouTube Video: “Charles Ives – The Unanswered Question” by Thomas Ligre

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Barber came from a traditional American home in Pennsylvania. He studied at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia and earned frequent commissions and awards. He also struggled with depression. In fact, his most known work, Adagio for Strings, has become something of a soundtrack for American tragedies; it was played on the broadcasts announcing the deaths of Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy and was frequently performed after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

Ex. 7.5: Samuel Barber, Adagio for Strings

It’s hard to describe what exactly makes this piece so emotive, but the slow tempo, softer dynamics, low strings, and frequent melodic descents characterize Barber’s Adagio for Strings.

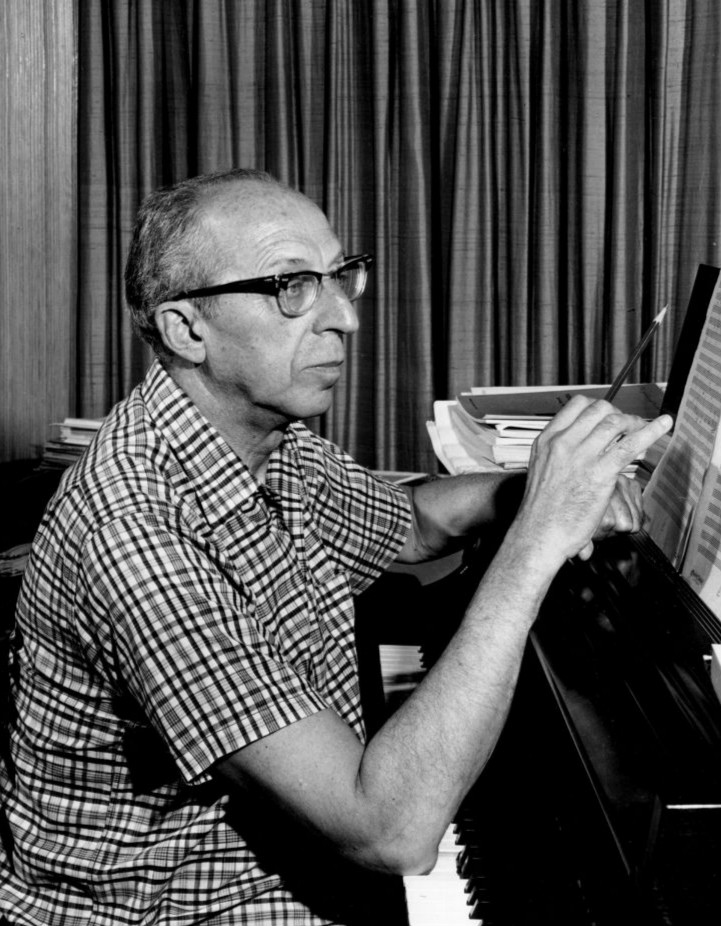

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

Aaron Copland was the first American composer with an acclaimed international reputation. He was the child of Jewish immigrants, grew up in New York, and as a young adult, he spent three years in Paris studying with Nadia Boulanger, a friend of Stravinsky and teacher to many of the twentieth century’s greatest composers. He said, “In greater or lesser degree, all of us discovered America in Europe,” and upon returning to America, created a sound embodying Americana, capturing the spirit of farm country and cowboys and the wide-open West. His music conveys the sound of the American frontier with open scoring: a heavy bass, a thin middle, and a clear high. While he used abstract and dissonant ideas like other Modernist composers, he also used American folk and popular songs.

Ex. 7.6: Aaron Copland, Fanfare for the Common Man

One of the ways Copland was able to capture the sense of vastness of the American landscape was through his use of certain harmonic intervals—two notes played together that sound “hollow” or “open.” These intervals, which are called “perfect 4ths” and “perfect 5ths,” have been used since medieval times, and were named “perfect” due to their simple harmonic ratios. The result is music that sounds vast and expansive. Perhaps the best example of this technique is found in Copland’s famous Fanfare for the Common Man. While fanfares are typically associated with heralding the arrival of royalty, Copland wanted to create a fanfare that celebrated the lives of everyday people during a trying time in American history. The piece was premiered by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra on March 12, 1943, at the height of World War II. It still stirs up patriotic emotions and has been used in countless movies, television shows, and even military recruitment ads. The piece came to define Copland’s uniquely American compositional style and remains one of the most popular patriotic pieces in the American repertoire.

Listening Guide: Copland, Fanfare for the Common Man

|

Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

|---|---|

|

0:00 |

Opening crash heralds introduction by bass drum and timpani that slowly dies down. Slow and deliberate. |

|

0:22 |

Slow fanfare theme enters. The melody itself is comprised of many perfect 4ths and perfect 5th intervals which convey a sense of openness. Unison trumpets. Slow tempo. No harmonic accompaniment creates a sense of starkness. |

|

0:49 |

After brief notes from the percussion section, French horns enter, moving a perfect 5th below the trumpets. Trumpets and French horns, with periodic hits from the percussion Built primarily on perfect 4ths and 5ths. |

|

1:17 |

Repeat of material from the introduction. Percussion followed by brass. |

|

2:02 |

Low brass enters with the main theme and is imitated by the horns and trumpets. Full brass and percussion. |

|

2:22 |

Melody is at ½ speed (augmentation) and ends on climactic chord. Full brass and percussion. |

Bonus Video: Copland, Piano Variations

While Copland’s music is widely accessible compared to other Modernist music—in fact, he wanted modern music that could appeal to the populace—he was no stranger to the abstract. For an example of such works, listen to his Piano Variations.

YouTube Video: “Hamelin plays Copland – Piano Variations Audio + Sheet music” by madlovba3

William Grant Still Jr. (1895-1978)

William Grant Still was born in Mississippi and grew up in Arkansas before attending the Oberlin Conservatory of Music. He achieved many milestones for Black composers (and, in general, American composers) and was called the “Dean of Afro-American Composers.” He’s often associated with the Harlem Renaissance, the early twentieth-century cultural and intellectual movement of African American arts, literature, and politics based in Harlem in New York City. He was the first American to write an opera performed by the New York City Opera and the first Black composer to have an opera performed on television. He was the first Black conductor of a prominent American symphony orchestra and the first Black composer to have a symphony performed by a prominent symphony orchestra.

Bonus Video: Still, Afro-American Symphony

For a time, this was the most performed symphony by any American.

YouTube Video: “Symphony No.1 in A-flat major “Afro-American” – William Grant Still” by Sergio Cánovas

Ex. 7.7: William Grant Still, To You America

This work was commissioned by the West Point Band; he was the first Black man to be commissioned by and conduct the ensemble. Still also served in the United States military during World War I. He aspired to write music of the same high quality coming from European composers but reflecting his American culture. Still wrote the following about this piece:

As for the composition I have written for West Point—it is a simple reaffirmation of the faith which all of us who are loyal Americans feel at this crucial time—our faith in our country and in its future. Musically speaking, it is a development of a single theme, energetic at the beginning and progressing to a majestic, choral-like Finale, pointing to a glorious destiny.

Meanwhile, Throughout the World

Most of the surviving records of Western music document trends and histories in Europe. A brief sample of other music throughout the world during these time periods include:

1877 – Thomas Edison invents the phonograph, allowing music and other sounds to be recorded and replayed.

1880’s – Vaudeville, a form of theatrical entertainment, becomes popular in the United States and Canada. Vaudeville performers would go on to influence early cinema and twentieth-century popular music.

1889 – Gamelan, a form of Indonesian music, is performed at the Eiffel Tower’s inauguration in Paris, France.

Attributions

Philosophical and artistic trend that seeks to abandon past traditions for new ideas.

Chord containing at least three adjacent notes.

Art or music based on the composer’s impression of an object, concept, or event.

Evoking foreign cultures.

Prevalently repeating phrase or musical idea.

A musical movement that arose in the twentieth century as a reaction against romanticism and which sought to recapture classical ideals like symmetry, order, and restraint.

Musical movement that arose as a reaction against musical impressionism and which focused on the use of strong rhythmic pulse, distinct musical ideas, and a tonality based on one central tone as a unifying factor instead of a central key or chord progression.

Dissonant, abstract style that rejects traditional depictions of beauty.

Derives musical elements such as pitch, duration, dynamics, and instrumentation from a series of the twelve tones of the chromatic scale.

Music that seeks to avoid both the traditional rules of harmony and the use of chords or scales that provide a tonal center.

Two or more different time signatures played at the same time.

A compositional technique where two or more instruments or voices in different keys (tonal centers) perform together at the same time.

Music that uses intervals smaller than the smallest standard intervals in Western equal-tempered music: half-steps or semitones.

Early twentieth century cultural and intellectual movement of African American arts, literature, and politics based in Harlem in New York City.