5 The Romantic

An Introduction to Romanticism

Aesthetics in the Classical Period were informed by ideas of reason and balance. In the Romantic Period, this gave way to influences of passion, emotion, love, nature, dreams, and the supernatural. Edgar Allan Poe was writing about the supernatural and the macabre, and artwork like Caspar David Friedric’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog demonstrates the idealization of getting lost in nature. Romanticism is characterized by restless longing and impulsive reaction, as well as freedom of expression and pursuit of the unattainable. There are many parallels between what was going on historically in society and what was occurring in music. We cannot study one without studying the other because they are so interrelated, though music will be our guiding focus.

Musically, melodies became longer and less symmetrical, harmonies became more striking and colorful, and rhythm became flexible. Composers designated more extremes in volume, called for more instruments in their orchestral works, and compositions became significantly longer; while Mozart’s 40th Symphony is approximately 25 minutes in duration, Mahler’s 2nd Symphony is nearly 90 minutes.

The Classical Period saw the role of the composer transform from servant to genius. Beethoven believed that music “would raise men to the level of gods;” it was no longer entertainment or ambience for an event. The concert hall became a sanctuary for the audience to silently revere masterpieces. Additionally, the importance of the individual expressing their own unique emotions became prevalent. To quote poet Walt Whitman, “I celebrate myself, and sing myself.”

19th Century Politics

Geo-politically, the nineteenth century extends from the French Revolution to a decade or so before World War I. The French Revolution wound down around 1799 when the Napoleonic Wars then ensued. The Napoleonic Wars were waged by Napoléon Bonaparte, who had declared himself emperor of France. Coal fueled the Industrial Revolution and the ever-expanding rail system. Economic and social power shifted increasingly towards the common people due to revolts. These political changes affected nineteenth-century music as composers began to aim their music at the more common people, rather than just the rich.

Political nationalism was on the rise in the nineteenth century. Early in the century, Bonaparte’s conquests spurred this nationalism, inspiring Italians, Austrians, Germans, Eastern Europeans, and Russians to assert their cultural identities, even while enduring the political domination of the French. After France’s political power diminished with the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815, politics throughout much of Europe were still punctuated by revolutions, first a minor revolution in 1848 in what is now Germany (and beyond), and then the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Later in the century, Eastern Europeans, in what is now the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and the Russians developed schools of national music in the face of Austro-German cultural, and sometimes political, hegemony. Nationalism was fed by the continued rise of the middle class as well as the rise of republicanism and democracy, which defines human beings as individuals with responsibilities and rights derived as much from the social contract as from family, class, or creed.

A Sample of Events from History and the Arts

- 1801: Wordsworth publishes his Lyrical Ballades

- 1814-1815: Congress of Vienna, ending Napoleon’s conquest of Europe and Russia

- 1815: Schubert publishes The Erlking

- 1818: Mary Shelley publishes Frankenstein

- 1818: Caspar David Friedrich paints Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog

- 1827: Beethoven dies

- 1830s: Eugène Delacroix captures revolutionary and nationalist fervor in his paintings

- 1830: Hector Berlioz premiers his most famous work, the Symphonie fantastique

- 1830s: Clara Wieck tours as virtuoso pianists

- 1831: Fryderyk Chopin immigrates to Paris, from the political turmoil in his native country of Poland

- 1848: Revolutions attempted in Sicily, France, Germany, Italy, and the Austrian Empire

- 1850s: Realism becomes prominent in art and literature

- 1853: Verdi composes La Traviata

- 1861-1865: Civil War in the U.S.

- 1870-71: Franco-Prussian War

- 1876: Johannes Brahms completes his First Symphony

- 1876: Wagner premiers The Ring of the Nibelungen at his Festival Theatre in Bayreuth, Germany

Philosophy

The nineteenth century saw some of the most famous continental philosophers of all time: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), and Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900). All responded in some way or another to the ideas of their eighteenth-century predecessor Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), who revolutionized the way human beings saw themselves in relation to others and to God by positing that human beings can never see “the thing in itself” and thus must relate as subjects to the objects that are exterior to themselves.

Science

Science and technology made great strides in the nineteenth century. Some of its inventions increased mobility of the individuals in the Western world, such as with the proliferation of trains running across newly laid tracks and steamships sailing down major rivers and eventually across oceans. Other advances such as the commercial telegraph (from the 1830s), allowed news to travel more quickly than before. All this speed and mobility culminated in the first automobiles that emerged at the very end of the century. First plate and then chemical photography was invented in the first half of the 1800s, with film photography emerging at the end of the century. We have photographs from this time period of several composers studied in this chapter. Experiments with another sort of recording, sound recording, began in the mid-1800s and finally became commercially available in the twentieth century. Romantics were fascinated by nature and the middle class followed naturalists, like Americans John James Audubon (1785-1851) and John Muir (1838-1914) and the Englishman Charles Darwin (1809-1882), as they observed and recorded life in the wild.

Visual Art

Romantics were fascinated by the imaginary, the grotesque, and by that which was chronologically or geographically foreign. Emphasis on these topics began to appear in such late eighteenth-century works as Swiss painter Henry Fuseli’s Nightmare from 1781.

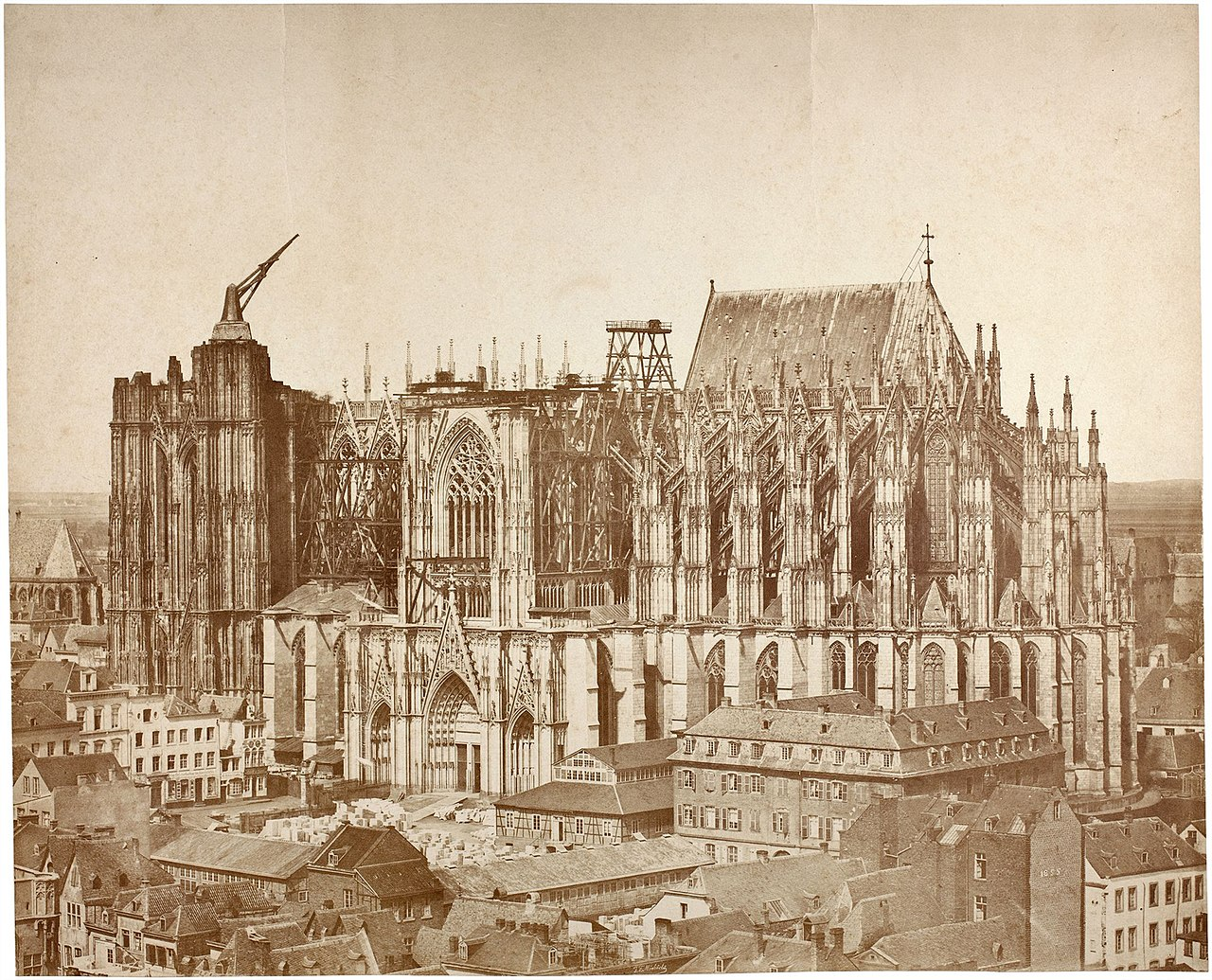

Romantics were also intrigued by the Gothic style; a young Goethe raved about it after visiting the Gothic Cathedral in Strasbourg, France. His writings, in turn, spurred the completion of the Cathedral in Cologne, Germany, which had been started in the Gothic style in 1248 and then completed in that same style between the years of 1842 and 1880.

Romantic interest in the individual, nature, and the supernatural is also very evident in nineteenth-century landscapes, including those of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). We earlier mentioned Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), which shows a lone man with his walking stick surrounded by a vast horizon. The man has progressed to the top of a mountain, but there his vision is limited due to the fog. We do not see his face, perhaps suggesting the solitary reality of a human subject both separate from and somehow spiritually attuned to the natural and supernatural.

Literature

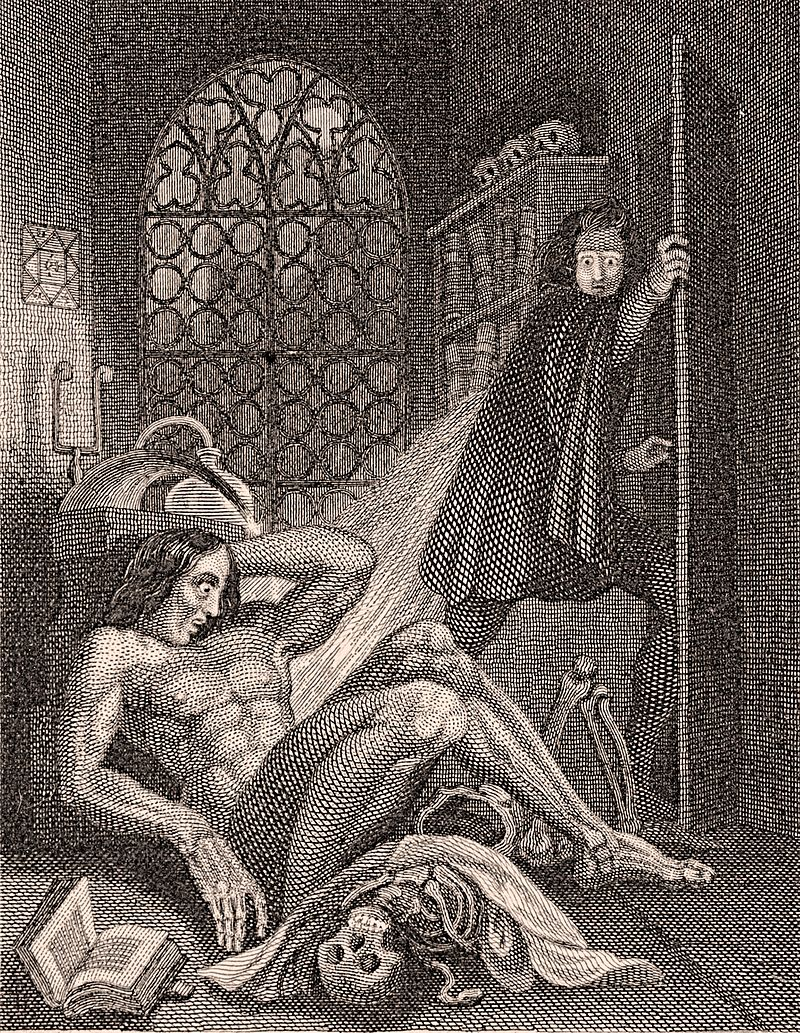

The novel, which had emerged forcefully in the eighteenth century, became the literary genre of choice in the nineteenth century. Many German novels focused on a character’s development; the most note-worthy of these novels are those by the German philosopher, poet, and playwright, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who was fascinated with the supernatural and set the story of Faust. Faust is a man who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for knowledge in an epic two-part drama. English author Mary Shelley (1797-1851) explored nature and the supernatural in the novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (1818), which examines current scientific discoveries as participating in the ancient quest to control nature; her book was a significant achievement in Gothic horror and helped establish the genre of science fiction. Later in the century, British author Charles Dickens exposed the plight of the common man during a time of industrialization. In France, Victor Hugo (1802-1885) wrote on a broad range of themes, from what his age saw as the grotesque in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) to the topic of French Revolution in Les Misérables (1862). Another Frenchman, Gustav Flaubert, captured the psychological and emotional life of a “real” woman in Madame Bovary (1856), and in the United States, Mark Twain created Tom Sawyer (1876).

Besides novels, poetry continued going strong in the nineteenth century with such important English poets as George Gordon, Lord Byron, Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and John Keats. In addition to Goethe, other German literary figures included Friedrich Schiller, Adrian Ludwig Richter, Heidrich Heine, Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, and E. T. A. Hoffmann; their works contributed librettos and settings for nineteenth-century music. Near the end of the century, French symbolism, a movement akin to Impressionism in art and music, emerged in the poetry of Paul Verlaine, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Arthur Rimbaud.

Art Song

The art song, also known by its German name, Lied, was a popular genre during the Romantic Period. Composers took contemporary poetry and set the words to a solo voice accompanied by piano. Many families had a piano, and before the invention of recorded music, playing and singing in the home was one of the most widespread ways of hearing music; this created a great demand for published art songs. Franz Schubert was the greatest writer of the art song, composing hundreds of them. Other European composers of the era include Robert and Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms. Beyond Europe, composers like Stephen Foster in the United States and Manuel Ponce also pursued art songs.

Schubert was born in Vienna in 1797, a few years after Mozart died. He showed musical talents as a child and sang in what would become the Vienna Boys’ Choir. He started his profession as a teacher, but left that work to devote his life to music. He struggled financially, often crashing on friends’ couches when he had nowhere else to stay. But, those who knew him loved his music; they put together Schubertiads, or private gatherings featuring Schubert’s music. Unfortunately, he died at a young age from syphilis, but he left a legacy of symphonies, chamber music, and hundreds of songs.

Ex. 5.1: Franz Schubert, “Erlkönig”

Schubert wrote the music for “Erlkönig” when he was a teenager. The text, written by German poet Goethe, tells the story of a traveling father and son and the evil Elf King who kills the child. While the song is sung by a single vocalist, it is sung from the points of view of four: the narrator, who introduces and concludes the song, a father and son, who each sing with a sense of panic, and the Elf King, whose music has a charming quality to seduce the child.

Bonus Video: Franz Schubert, “Erlkönig”

For an animation that visually tells the story of Schubert’s Erlkönig, check out this video.

YouTube Video: “Franz Schubert: Erlkönig” by OxfordSong

Many songs are written in strophic form (the music stays the same from stanza to stanza), but “Erlkönig” is through-composed: the music changes from stanza to stanza to reflect the story.

Listening Guide: Franz Schubert, Erlkönig

|

Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text Translation |

|---|---|---|

|

0:00 |

Opens with a fast tempo melody that begins low in the register, ascends through the minor scale, and then falls. Accompanied by repeated triplet octaves. The ascending/descending melody may represent the wind. The minor key suggests a serious tone. The repeated octaves using fast triplets may suggest the running horse and the urgency of the situation. |

(Piano introduction ) |

|

0:24 |

Voice and piano from here to the end; Performing forces are voice and piano in homophonic texture from here to the end. Melody falls in the middle of the singer’s range and is accompanied by the repeated octave triplets. |

Narrator: Who rides so late through night and wind? |

|

0:56 |

Melody drops lower in the singer’s range.

|

Father: My son, why are you frightened? |

|

1:03 |

Melody shifts to a higher range

|

Son: Do you see the Erlking, father?

|

|

1:19 |

Melody lower in range. |

Father: It is the fog. |

|

1:28 |

The key switches to major, perhaps to suggest the friendly guise assumed by the Erlking. Note also the softer dynamics and lighter arpeggios in the piano accompaniment |

The Erlking: Lovely child, come with me… |

|

1:52 |

Back in minor the melody hovers around one note high in the singer’s register; the minor mode reflects the son’s fear, as does the melody, which repeats the same note, almost as if the son is unable to sing another |

Son: My father, father, do you not hear it… |

|

2:03 |

Melody lower in range |

Father: Be calm, my child, the wind blows the dry leaves… |

|

2:13 |

Back to a major key and piano dynamics for more from the Erlking |

The Erlking: My darling boy, won’t you come with me… |

|

2:30 |

Back to a minor key and the higher-ranged melody that hovers around one pitch for the son’s retort.

|

Son: My father, can you not see him there? |

|

2:41 |

Melody lower in range and return of the louder repeated triplets |

Father: My son, I see well the moonlight on the grey meadows….

|

|

2:58 |

Momentarily in major and then back to minor as the Erlking threatens the boy |

The Erlking: I love you…if you do not freely come, I will use force… |

|

3:09 |

Back to a minor key and the higher-ranged melody that hovers around one pitch. |

Son: My father, he has seized me… |

|

3:22 |

Back to a mid-range melody; the notes in the piano get faster and louder. |

Narrator: The father, filled with horror, rides fast |

|

3:37 |

Piano accompaniment slows down; dissonant and minor chords pervasive; song ends with a strong cadence in the minor key; Slowing down of the piano accompaniment may echo the slowing down of the horse. The truncated chords and strong final minor chords buttress the announcement that the child is dead. |

Narrator: They arrive at the courtyard. In his father’s arms, the child was dead.

|

Program Music

The nineteenth century is especially known for program music, or instrumental music that conveys a nonmusical narrative: historical events, legends, literature, etc. It parallels a time in history when many novels and short stories were being written and widely read: Goethe’s poetry, the Brothers Grimm’s collection of folk tales, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Victor Hugo’s stories and novels, and many, many others. Composers used music to convey these extramusical ideas: a song-like melody for love, dissonant chords for anguish, and the diverse colors from the ever-enlarging orchestra to reflect moods.

The three most common types of program music were:

Dramatic overture: a one-movement work, usually in sonata-allegro form, that presented a musical narrative. This often preceded an opera, play, or some other event.

Tone poem (also called symphonic poem): a one-movement work for orchestra that conveys a story, event, or experience. Musically, it’s very similar to a dramatic overture, except that the tone poem is a stand-alone work; it doesn’t lead into a larger work.

Program symphony: a multi-movement work depicting a series of events. While the classical symphony followed a specific form with its movements, the different movements of the program symphony were used to tell a story.

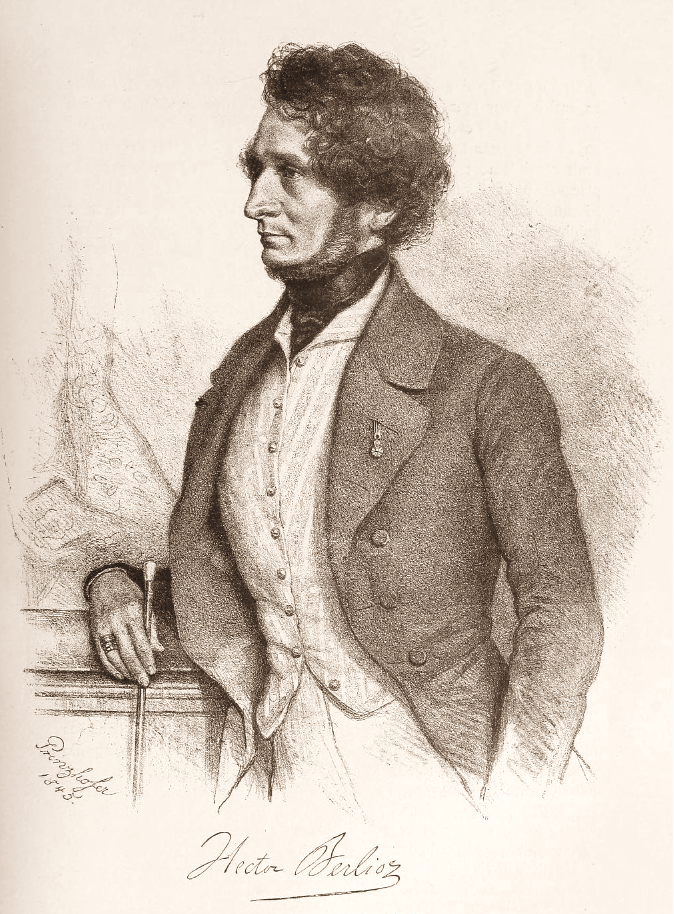

Hector Berlioz and the Program Symphony

Unlike most composers we’ve encountered so far, Hector Berlioz was not a skilled performer on an instrument. When he couldn’t sustain an income as a performer or instructor, he supported himself as a music writer and critic. Despite his lack of performance abilities, he knew how to write for the instruments of the orchestra (his orchestration text is still used today) and he dreamed of an orchestra and chorus with hundreds and hundreds of musicians. He introduced a number of new instruments to the orchestra: the English horn, the ophicleide (predecessor to the tuba), the saxophone, the cornet (similar to a trumpet), and various percussion instruments.

Berlioz influenced future orchestral composers with his new sounds and instruments. The caricature below (figure 5.8) reflects how some critics viewed his music as simply noise.

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) was born in France in La Côte-Saint-André, Isère, near Grenoble. His father was a wealthy doctor and planned on Hector pursuing the profession of a physician. At the age of eighteen, Hector was sent to study medicine in Paris. Music at the Conservatory and at the Opera, however, became the focus of his attention. A year later, his family grew alarmed when they realized that the young student had decided to study music instead of medicine. At this time, Paris was in a Romantic revolution. Berlioz found himself in the company of novelist Victor Hugo and painter Delacroix.

As a young student, Berlioz was amazed and intrigued by the works of Beethoven. Berlioz also developed an interest in Shakespeare, whose popularity in Paris had recently increased with the performance of his plays by a visiting British troupe. Hector became impassioned for the Shakespearean characters of Ophelia and Juliet as they were portrayed by the alluring actress Harriet Smithson. Berlioz became obsessed with the young actress and also overwhelmed by sadness due to her lack of interest in him as a suitor. Berlioz became known for his violent mood swings, a symptom commonly associated with a condition known today as bipolar disorder.

In 1830, Berlioz earned his first recognition for his musical gift when he won the much sought-after Prix de Rome. This highly esteemed award provided him a stipend and the opportunity to work and live in Paris, thus providing Berlioz with the chance to complete his most famous work, the Symphonie fantastique, during that same year. Upon his return to Rome, he began his intense courtship of Harriet Smithson. Both of their families vehemently opposed their relationship. Several violent and arduous situations occurred, one of which involved Berlioz’s unsuccessful suicide attempt. After recovering from this attempt, Hector married Harriet. Once the previously unattainable matrimonial goal had been attained, Berlioz’s passion somewhat cooled, and he discovered that it was Harriet’s Shakespearean roles that she performed, rather than Harriet herself, that really intrigued him. The first year of their marriage was the most fruitful for him musically. By the time he was forty, he had composed most of his famous works.

Symphonie fantastique is one of the most famous examples of a program symphony, a multi-movement work written around a narrative structure. His treatment of the orchestra, the form, and the narrative, were all remarkably innovative. In addition to the larger orchestra, Berlioz’s formal organization of Symphonie fantastique differed from the standard forms Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven used in their symphonies. Each of the five movements was like a different musical episode of a miniseries. In the program notes, which were new for the time, he narrates the story of a musician, obsessed with a woman upon first sight, who goes on a drug-induced nightmare. He based the obsession on his own. Each of the five movements includes a recurring melody called an idée fixe (“fixed idea”) that represents the woman of the character’s obsession.

Ex. 5.2: Hector Berlioz, Symphonie fantastique, fourth movement (“March to the scaffold”)

In this movement, the main character walks to the guillotine for his execution. A band plays a march theme that represents the excitement of the gathered crowd, and a crashing chord signifies the moment of beheading. These new sounds of the orchestra, accompanied by the narrative, shocked the audience at its premiere.

For more thoughts on the reception of Berlioz, read this NPR interview:

Deceptive Cadence | At 92, The Man Who Wrote The Book On Berlioz Resumes His Case

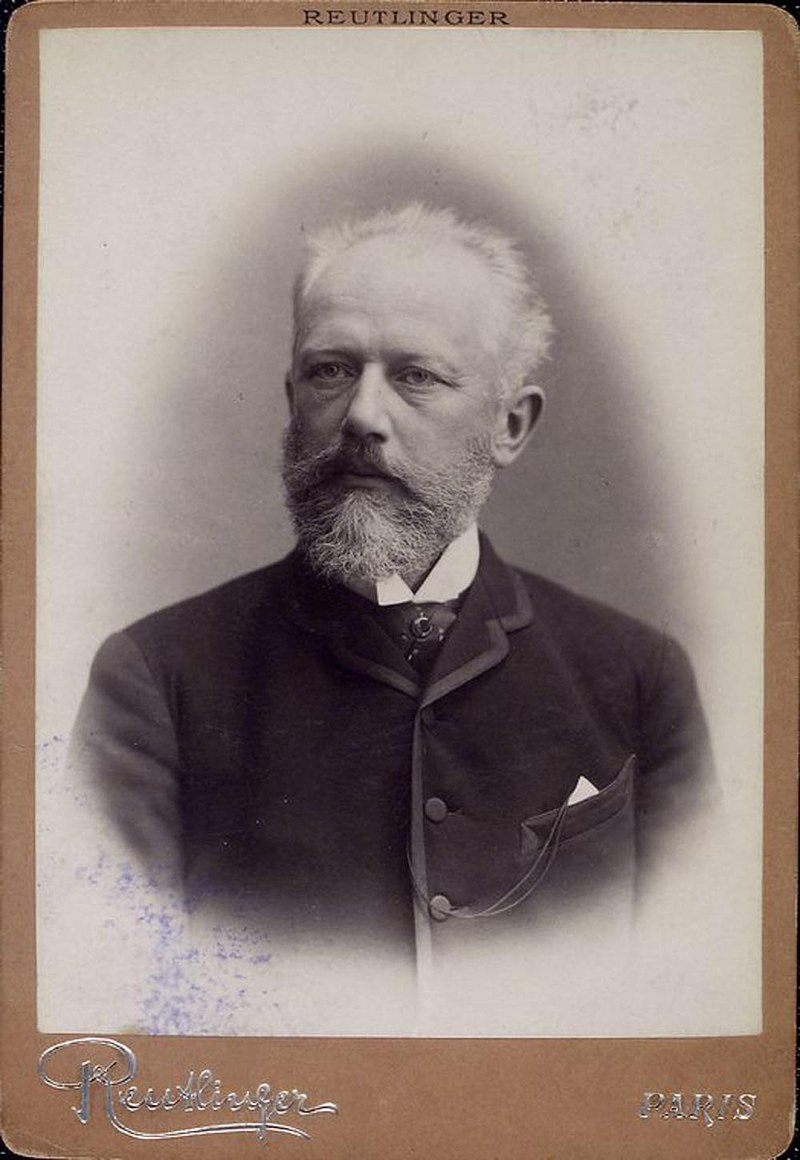

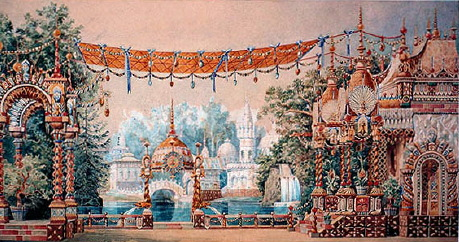

Peter Tchaikovsky (1840-1893): Tone Poem and Ballet Music

Tchaikovsky showed musical talent at an early age. His parents wanted him to study law, but music was his passion. Upon graduating from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory of Music, he was hired to teach music at the new Moscow Conservatory. In addition to that income, he received further stipends from a music-loving widow and Tsar Alexander III. By the end of the nineteenth century, he was the world’s most popular orchestral composer.

In the nineteenth century and still today, Tchaikovsky is among the most highly esteemed of composers. Russians have the highest regard for Tchaikovsky as a national artist. Tchaikovsky incorporated the national emotional feelings and culture—from its simple countryside to its busy cities—into his music. Along with his nationalist influences, such as Russian folk songs, Tchaikovsky enjoyed studying and incorporating German symphony, Italian opera, and French Ballet. He was comfortable with all of these disparate sources and gave all his music lavish melodies flooding with emotion.

Tchaikovsky composed a tremendously wide spectrum of music, with ten operas, several internationally acclaimed ballets (including Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker), six symphonies, concertos, various overtures, chamber music, piano solos, songs, and choral works.

Ex. 5.3: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Romeo and Juliet (excerpt)

Many of Tchaikovsky’s works were tone poems, which he titled “overture,” “overture fantasy,” or “symphonic fantasy.” His Romeo and Juliet captures the essence of the Shakespeare play in a twenty-minute, single-movement work in sonata-allegro form with three main themes: the gentle music of Friar Laurence that introduces the work, the tension-filled theme of the warring Capulets and the Montagues, and the theme of love between Romeo and Juliet.

Ballet—a story told through dramatic dance—was originally linked to Baroque opera. Serious opera works typically had a ballet or two, and the first professional ballet company, Paris Opera Ballet, was an offshoot of the Paris Opera Company, however, during the nineteenth century, ballet became an independent genre.

Music historians sometimes criticize Tchaikovsky for not having the compositional chops to develop or transform motives throughout a composition like Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven. However, he had a tremendous gift for melody and creating moods. He created beautiful and timeless melodies for their own sake, not necessarily for motivic development. Tchaikovsky realized he could use these skills for ballet, which required capturing different moods from moment to moment.

Ex. 5.4: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, The Nutcracker, “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy”

The Nutcracker, often associated with the holidays, is among Tchaikovsky’s most famous works. It tells the story of a young girl named Clara, exhausted after Christmas celebrations, who dreams of traveling to exotic locations and toys that come to life. “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” is in ternary, or three-part, form (ABA).

For more from The Nutcracker, find and watch a video of “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” from the Disney film Fantasia.

Music and Nationalism

The nineteenth century witnessed a growing sense of nationalism in many European countries, especially for groups seeking independence from foreign leaders such as the Greeks against the Turks, the Belgians against the Dutch, the Finns against the Russians, and the Czechs against the Austrians. Music helped foster ethnic pride, using local songs, dances, scales, rhythms, instruments, and stories or histories (for example, dramatic works based on the folklore of peasant life or celebration of a national hero, historic event, or scenic beauty of the country).

This sense of Nationalism was not limited to Europe. The United States after the War of 1812 experienced the Era of Good Feelings—an increase in national unity and a feeling of national purpose. There was a desire to create uniquely American music, art, and literature to distinguish themselves from others. Several reform movements swept the nation during this time as well, including calls for the abolition of slavery. In fact, songs were used to help Black slaves from the Southern United States escape slavery through the Underground Railroad. Many of these songs were sung in a call-and-response style. The lyrics to songs like “Wade in the Water” and “Follow the Drinking Gourd” were actually coded messages with directions to safe houses and how to escape slave catchers.

Several nations in Latin America took up their own revolutions for independence following the success of the American Revolution. They desired their own national identities free from European influence. Many of these nations modeled their new governments and constitutions after the United States. The nations of the Western Hemisphere were creating and celebrating their own identities separate from the European nations that colonized them (O’Neel, 2021).

Prior to the nineteenth century, Russia didn’t have the same reputation for high art as other European countries, and they began importing or adapting German orchestral music, French ballet, and Italian opera. But, beginning with Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar, Russian composers incorporated more native elements into their music. Modest Mussorgsky used the most innovative and least traditional (by European standards) ideas. Mussorgsky’s life was troubled with alcoholism and poverty, but he managed to create a body of work including the tone poem Night on Bald Mountain (often used in popular media to depict monsters), the opera based on Russian tsar Boris Godunov, and Pictures at an Exhibition, which musically portrayed a gallery of artwork with solo piano.

Ex. 5.5: Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition, Promenade

This series of movements conveying an art exhibition was originally written for the piano. The Promenade is a recurring melody in Pictures at an Exhibition, musically depicting moving from one painting to another in the gallery.

Ex. 5.6: Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition, The Great Gate of Kiev

The majestic work in rondo form consists of three main musical ideas: a triumphant main theme, a reserved depiction of Russian Orthodox chant, and a brief return of the Promenade theme as if the viewer of the pictures in the gallery is walking through the great gate.

Bonus Video: Mussorgsky (orch. Ravel) – Pictures at an Exhibition

French composer Maurice Ravel orchestrated Pictures at an Exhibition to add more colors to Musorgsky’s melodies and harmonies.

YouTube Video: “Mussorgsky (orch. Ravel) – Pictures at an Exhibition – Complete (Official Score Video)” by Boosey & Hawkes

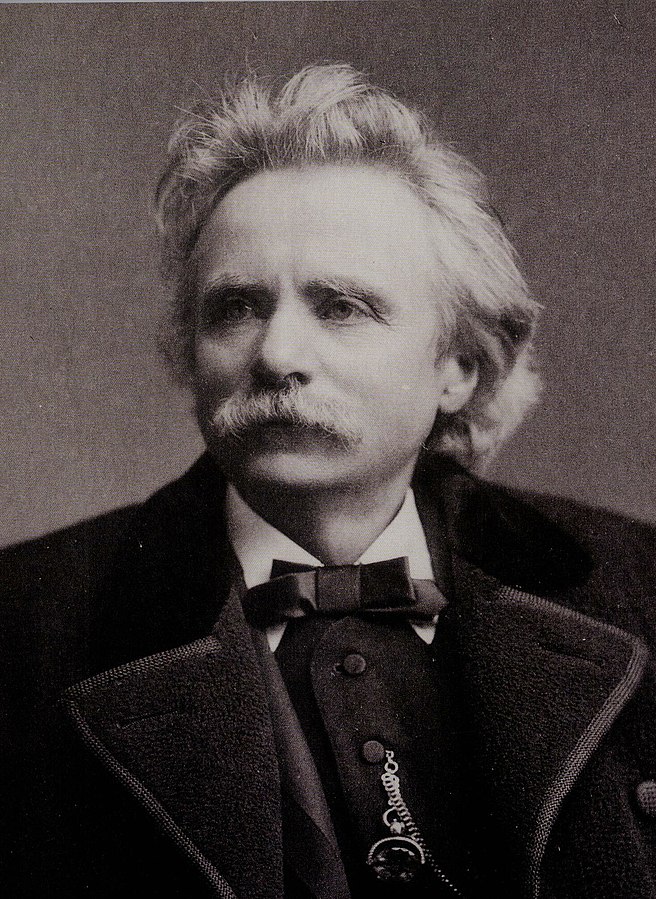

Ex. 5.7: Edvard Grieg, “In the Hall of the Mountain King”

Grieg (1843-1907) was a Norwegian pianist and composer; he helped create a Norwegian national music identity and used Norwegian folk tunes in his internationally-famous compositions. “In the Hall of the Mountain King” was written as part of a suite to accompany the Norwegian fairy tale of Peer Gynt, who travels to distant lands. The piece depicts the main character approaching the throne of the troll Mountain King, who wants Peer Gynt to become a troll and marry his daughter. Peer Gynt refuses and flees. A chase ensues. The piece starts quiet, but it becomes louder and louder, increasing in drama and excitement.

Interested in exploring more examples of nationalism in music? Check out Bohemian composers such as Antonin Dvorak and Bedřich Smetana; Hungarian composers such as Liszt; Scandinavian composers such as Edvard Grieg and Jean Sibelius; Spanish composers such as Enrique Granados, Joaquin Turina, and Manuel de Falla; and British composers such as Ralph Vaughn Williams.

Piano Music

As we learned in Chapter 4, the piano (short for pianoforte, meaning it could play soft and loud dynamics) emerged during the Classical period. The piano of Mozart’s day had 61 keys and weighed less than 200 pounds. The piano of the Romantic period, the design of which is still prevalent today, had 88 keys, weighed 1000 pounds, and included different pedals that could sustain or soften the sounds. Composers, including some incredibly virtuosic individuals, were attracted to this technologically advanced piano.

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849) was born in Poland. His family was a member of the educated middle class; consequently, Chopin had contact with academics and wealthier members of the gentry and middle class. He learned as much as he could from the composition instructors in Warsaw—including the keyboard music of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven—before deciding to head off on a European tour in 1830. The first leg of the tour was to Vienna, where Chopin expected to give concerts and then head further west. About a week after his arrival, however, Poland saw political turmoil in the Warsaw uprising, which eventually led to the Russian occupation of his home country. After great efforts, Chopin secured a passport and, in the summer of 1831, traveled to Paris, which would become his adopted home. Paris was full of Polish émigrés, who were well-received within musical circles.

Chopin’s first compositions were designed to impress his audiences with his virtuoso playing. As he grew older and more established, his music became more subtle. Paris was amazed by his abilities, but the introverted Chopin preferred playing for private gatherings instead of the public concert hall. While contemporary composers wrote for a variety of instrumentations and were especially drawn to the colors and powers of the orchestra, Chopin focused on piano writing and wrote a body of work that is especially loved by pianists. He was particularly influential with his prevalent use of rubato as a performance instruction in his musical scores, indicating a flexible ebb and flow of the speed.

Composer, pianist, and music critic Robert Schumann, in the publication Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (“[The] New Journal of Music”), wrote of a young Chopin: “Hats off, gentleman — a genius!”

Ex. 5.8: Frédéric Chopin, Prelude in E Minor

Chopin had a copy of J.S. Bach’s Preludes and Fugues in every major and minor key, and wrote his own collection of preludes in every key. Chopin’s Preludes were original in that they were standalone pieces, not pieces designed to introduce a more substantial piece. Chopin’s captivating sense of melody was informed by bel canto (“beautiful singing”) opera that he encountered shortly after moving to Paris.

Clara Wieck Schumann (1819-1896) was a virtuosic pianist who toured and composed. She is a historical side note, mostly known for her composer husband Robert Schumann, and her association with close friend, Johannes Brahms. But she was a strong musician and composer and well-known in a time where women did not have professional careers outside the home. She had many children, supported her husband intellectually with his compositional endeavors, supported her husband emotionally when he was suffering from mental instabilities, and supported her family financially when needed. She balanced all the roles with professionalism and grace (Laufman).

Robert Schumann died after struggling with psychosis. After his death, Clara returned to a more active career as a performer. She spent the rest of her life supporting her children and grandchildren through her public appearances and teaching. She is quoted as conveying an unfortunately common sentiment of the time that “women are not born to compose.” However, she composed a number of remembered pieces during the middle of her career, and it’s possible that her busy performing calendar after Robert’s death prevented her from composing even more pieces.

Ex. 5.9: Clara Schumann, Scherzo no. 2, Op. 14

This piece shows off Clara’s virtuosic abilities; the arpeggios (different notes of a chord played one at a time) create a stormy effect and reflect the influence of Chopin, who Clara Schumann greatly respected as a pianist.

Chamber Music

In the Classical Era, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven wrote much celebrated chamber music, played by small groups and often in small and intimate settings. The string quartet was an especially popular genre of chamber music. Romantic composers experimented with different combinations of small ensembles with various winds, strings, and piano: trios, quartets, quintets, sextets, and octets.

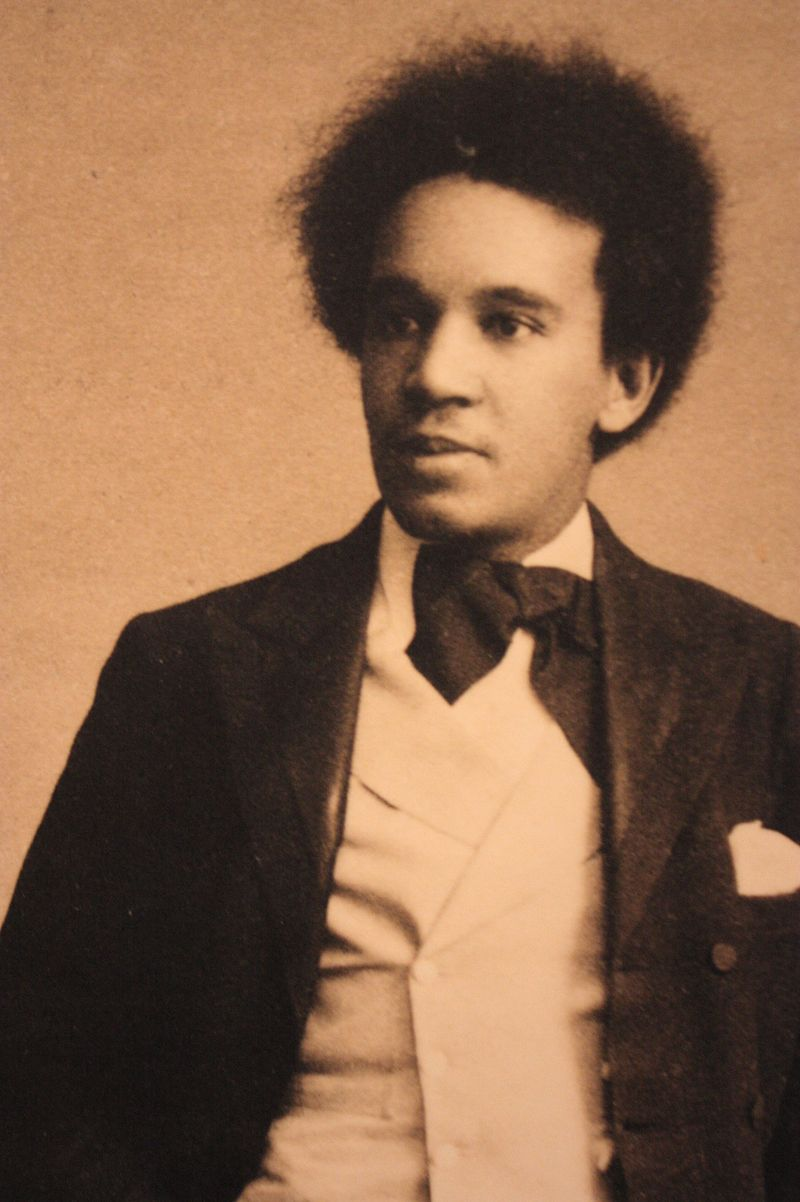

Ex. 5.10: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, They Will Not Lend Me A Child, Op. 59 No. 4, for Piano Trio

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) was born to a woman from England and a man from Sierra Leone. An Anglo-African composer, he was named after English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. On multiple occasions, he traveled to the United States to great acclaim. He was even welcomed to visit President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House in 1904; at a time of rampant racial segregation in the United States, it was rare for a Black person to be welcomed by the president.

Coleridge-Taylor wrote many settings of African-American spirituals; They Will Not Lend Me A Child was included in his collection Five Negro Melodies for Piano Trio. Taylor’s setting is very dignified and reverent. Building slowly, it reaches an ecstatic culmination that yet retains the quasi-religious feeling of the original melody.

Late Romantic Orchestral Music

The symphony orchestra reached its height as a genre of Western art in the late nineteenth century. It was a time period that saw construction of some of the greatest music halls in the world that were devoted almost exclusively to instrumental music. A canon of great works was established going back to Haydn, almost creating a museum of the best orchestral works. Interestingly, the experience of a concert-goer of the late nineteenth century wouldn’t differ significantly from one of today. They would hear much of the same repertoire, and perhaps even be attending the same venue.

That being said, after Beethoven, composers weren’t writing as many symphonies. There was no shortage of orchestral works, but these were predominantly tone poems with an attached narrative. The Romantic period saw a rise in program music, music with a story, but the orchestral world saw less absolute music, music without a driving narrative. After Beethoven had brought the symphony to such great heights, some composers like Wagner thought there was nothing new to add to the genre, and other composers interested in the genre were too intimidated to tackle it. It was nearly a half-century before Brahms would serve as Beethoven’s successor to the symphony.

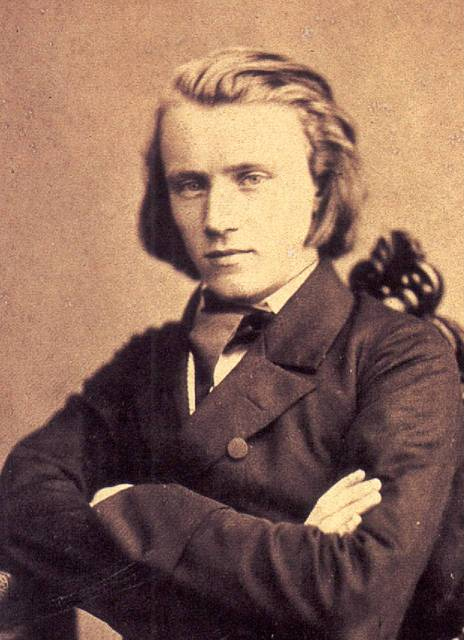

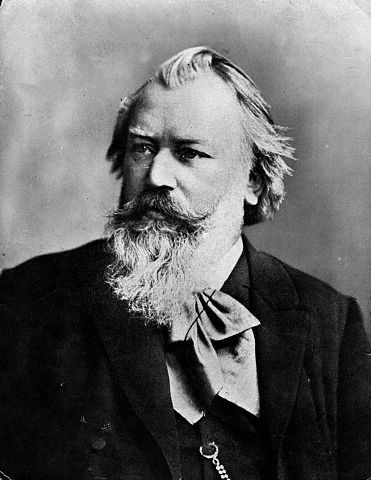

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Brahms was born in Hamburg, a German port city. Musically, he was brought up on Bach and Beethoven, but by night, he made money by playing piano at bars. Robert Schumann took note of Brahms’ talent, praising him as the next great composer after Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven; both Schumanns became his mentors. Brahms made Vienna his home and worked with the traditional forms of the classical masters: symphony, concerto, and string quartet—forms not propelled by a story or program.

Whereas Berlioz’s program symphony might be heard as a radical departure from earlier symphonies, the music of Johannes Brahms is often thought of as breathing new life into classical form. For centuries, musical performances were by composers who were still alive and working. In the nineteenth century that trend changed. By the time Johannes Brahms was twenty, over half of all music performed in concerts was by composers who were no longer living; by the time he was forty, that amount increased to over two-thirds.

Brahms knew and loved the music of forebears such as Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann. He wrote in the genres they had developed, including symphonies, concertos, string quartets, sonatas, and songs. To these traditional genres and forms, he brought sweeping nineteenth-century melodies, much more chromatic harmonies, and the forces of the modern symphony orchestra. He did not, however, compose symphonic poems or program music as did Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt.

Brahms himself was keenly aware of walking in Beethoven’s shadow along with the public’s expectations for his own potential. Composer, pianist and music critic Robert Schumann, in the publication Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (“[The] New Journal of Music”), had written the following of a young Brahms:

This is a chosen one. Sitting at the piano, he began to reveal wonderful regions.

We were drawn into ever more magical spheres. There came about an entirely brilliant performance, that made the piano into an orchestra of lamenting and jubilant voices.

If he were to wave his magic wand where the massed powers of the chorus and orchestra lend him their force, even more wonderful glimpses into the mysteries of the spirit world would be in store for us. May the highest genius lend him strength, for which the prospects are good, for another genius, that of modesty, dwells within him.

In the early 1870s, Brahms wrote to conductor friend Hermann Levi, “I shall never compose a symphony.” Continuing, he reflected, “You have no idea how someone like me feels when he hears such a giant marching behind him all of the time.” Nevertheless, some six years later, after a twenty-year period of germination, he premiered his first symphony. Brahms’s music engages Romantic lyricism, rich chromaticism, thick orchestration, and rhythmic dislocation in a way that clearly goes beyond what Beethoven had done. Still, his intensely motivic and organic style, and his use of a four-movement symphonic model that features sonata, variations, and ABA forms is indebted to Beethoven.

Ex. 5.11: Johannes Brahms, Symphony No. 3, third movement

By the time Brahms had written his third symphony, he was an acclaimed composer with overtures, concertos, and symphonies already written. This waltz-like third movement is one of the most remembered of his four symphonies for its poignant melodies.

Bonus Video: Frank Sinatra, “Take My Love”

This movement is often used in popular culture. Legendary pop singer Frank Sinatra even sang a song that used its main melody, “Take My Love.”

YouTube Video: “Frank Sinatra – Take My Love.flv” by Maks Grynkiv

Bonus Video

A humorous public service announcement about the power of the arts and a Johannes Brahms-themed cereal.

YouTube Video: “Americans For The Arts – ‘Brahm’s Breakfast'” by CrossroadsFilms

Amy Beach (1867-1944)

Amy Beach was one of the first American composers to achieve international acclaim. She was a musical prodigy: being able to sing 40 songs at age one, harmonizing with her mother’s lullabies at age two, soon after composing pieces in her head, and performing Beethoven pieces at age seven.

If she were a boy, she might have been sent to Europe to receive the best music education possible. Unfortunately, such an opportunity wasn’t considered appropriate for girls at the time; she found tutors in America and read all she could about music. Her studies paid off; she was the first American woman to have a symphony published. She wrote a number of critically acclaimed pieces. She would perform across Europe and teach music lessons in the United States. In a time when women composers were a rarity, and when American composers weren’t respected on the international stage, she did, in her own words, “pioneer work.”

Ex. 5.12: Amy Beach, Mass in E-flat Major, “Kyrie”

Beach’s Mass, the first known Mass composed by an American woman, was premiered by the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston. The Mass was a success. Like masses of previous centuries, the Kyrie sets the words “Kyrie eleison” and “Christe eleison” – “Lord have mercy” and “Christ have mercy.”

Meanwhile, Throughout the World

Most of the surviving records of Western music document trends and histories in Europe. A brief sample of other music throughout the world during these time periods include:

1821 – Levi Coffin, a Quaker who helped thousands of American slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad, documents African American spirituals.

1833 – Guitarist José de la Rosa moves to California, where he documented the earliest known Mexican-Californian songs

1849-1852 – The California Gold Rush brings Chinese immigrants to the United States, who bring their traditions of folk songs and Cantonese opera.

Attributions

This chapter was adapted from Understanding Music: Past and Present by N. Alan Clark, Thomas Heflin, Jeffrey Kluball, and Elizabeth Kramer from the University System of Georgia, licensed by a CC BY-SA 4.0 international license.

Works Cited

Laufman, Alana. “Clara Schumann Biography.” The Clara Schumann Project, https://claraschumannproject.com/about-2/. Accessed September 2021. Shared with permission.

O’Neel, Jessica. “Nationalism in the Americas.” E-mail to the author. 22 Nov. 2021. Shared with permission.

German art song, particularly with solo voice and piano accompaniment.

An event to perform and celebrate the music of Franz Schubert.

A composition that uses the repetition of the same music (“strophes”) for successive texts.

A movement or composition consisting of new music throughout, without repetition of internal sections.

Instrumental music intended to represent something extra-musical such as a poem, narrative, drama, or picture, or the ideas, images, or sounds therein.

A one-movement work, usually in sonata-allegro form, that presented a musical narrative. This often preceded an opera, play, or some other event.

Also called symphonic poem. A one-movement work for orchestra that conveys a story, event, or experience. Musically, it’s very similar to a dramatic overture, except that the tone poem is a stand-alone work. It doesn’t lead into a larger work.

Program music in the form of a multi-movement composition for orchestra.

Information in a concert program about a piece of music.

Performance dance.

Instrumental form consisting of the alternation of a refrain “A” with contrasting sections (“B,” “C,” “D,” etc.). Rondos are often the final movements of string quartets, classical symphonies, concerti, and sonata (instrumental solos).

The momentary speeding up or slowing down of the tempo within a melody line, literally “robbing” time from one note to give to another.

Playing the notes of a chord one at a time instead of simultaneously.

A type of Black American Christian song.

Non-representational music.