3 The Baroque

Introduction

During the Baroque period, music, like visual art of the time, contained numerous small details and ornamentations while being monumental in scope. The origins of opera, the rising popularity of instrumental music, and the late Baroque figures of Handel and Bach were especially important during this time.

As we dive into the music of the Baroque, it’s worth reviewing what the term “Baroque” means—the word comes from the Portuguese barroco, irregularly shaped pearls used for decor and jewelry. Related terms include extravagant, ornate, excessive, rough, bold, and convoluted. Originally, the term was used negatively, to describe a work that was ornamented to the point of distortion or excess. If you like it, it comes across as detailed and rich. If you don’t, it appears busy, jagged, and over-the-top. What do you think about Baroque music and art? Do all of the ornaments and details appeal to you, or do they make it too busy?

Generally speaking, musically, Baroque works tended to use the same general rhythmic patterns and convey the same general mood or affect throughout a piece; composers began indicating the dynamics, or volume, or their pieces, and dynamics would dramatically shift from loud to soft or soft to loud.

A Sample of Events from History and the Arts

- 1607: Monteverdi performs Orfeo in Mantua, Italy

- 1618-1648: Thirty Years War

- 1623: Galileo Galileo publishes The Assayer

- 1642-1651: English Civil War

- 1643-1715: Reign of Louis XIV in France

- 1649: Descartes publishes Passions of the Soul

- 1678: Vivaldi born in Venice, Italy

- 1685: Handel and Bach born in Germany

- 1687: Isaac Newton publishes his Principia

- 1741: Handel Messiah performed in Dublin, Ireland

- 1750: J. S. Bach dies

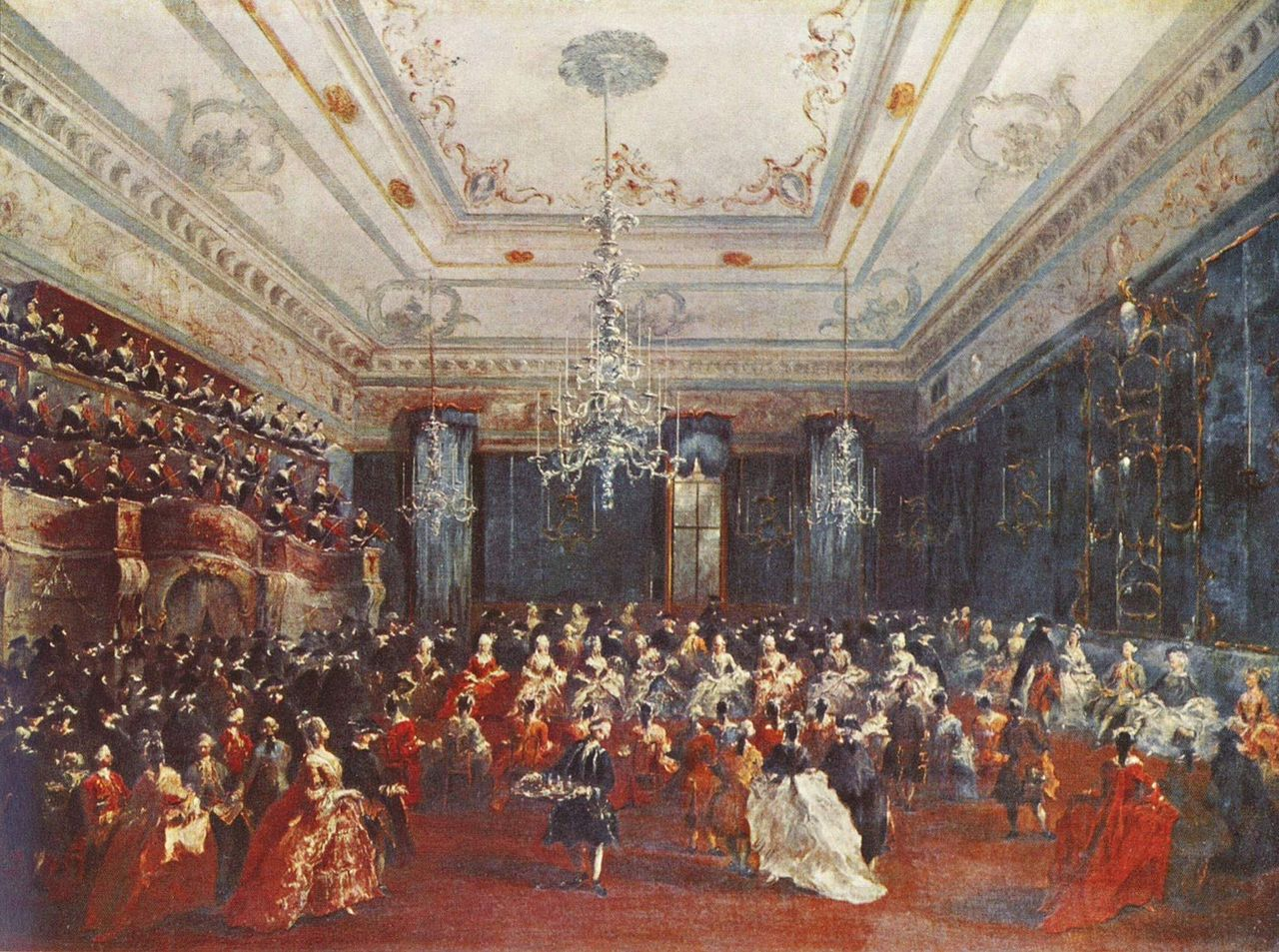

Baroque Architecture and Music

For examples of Baroque architecture, consider images of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (particularly the tall altar canopy in Figure 3.2 below) or the Palace of Versailles (Figure 3.1 above). Note how large surfaces are covered in ornate detail, from smaller sculptures to gold leaf patterns. In comparison, Baroque music is supported by a foundation called “basso continuo,” where a few performers build a harmonic foundation of chords over a moving bassline—the melody sitting on top of this support is filled with all sorts of ornamentations and embellishments.

Baroque Painting and Music

The Baroque is interested in the dramatic, and this is especially seen in painting. The subjects are often dramatic, as in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes. There are often strong contrasts in colors and lights and darks. In addition to Gentileschi, find some images of Baroque painters like Rubens or Caravaggio. Note how dark and light sharply contrast against each other or the powerful, emotional imagery. Baroque music often sought to evoke a specific emotion; an entire piece would reflect one mood. Contrast was used to stark effect in music, like the terraced dynamics (sudden and dramatic changes in volume) or changes in texture.

Early Baroque Opera

During the Medieval and Renaissance periods, we saw music develop in complexity from monophonic melodies to polyphonic works. However, around 1600 in Italy, a group of thinkers, the Florentine Camerata (which included the father of the astronomer Galileo Galilei), believed that solo voices could better convey the emotion of a text than Renaissance polyphony, and a new kind of song emerged called “monody” (Greek for “solo song”). Without other singers to coordinate with, this gave the soloists considerable freedom to elaborate their melodies—both to convey drama and to show off their talents. Compare the embellishments you hear in the listening examples with the fine levels of detail you see in Baroque architecture and sculpture.

Basso continuo helped realize this new style of monody. Basso continuo is a continuous bass line over which the harpsichord, organ, or lute added chords based on numbers or figures that appeared under the melody that functioned as the bass line, would become a defining feature of Baroque music. This system of indicating chords by numbers was called figured bass and allowed the instrumentalist more freedom in forming the chords than if every note of the chord had been notated. The flexible nature of basso continuo also underlined its supporting nature. The singer of the recitative was given license to speed up and slow down as the words and emotions of the text might direct, with the instrumental accompaniment following along. This method created a homophonic texture, which consists of one melody line with accompaniment

A prevailing thought was that Greek art was of the highest caliber; they assumed their idea of music was how the Greeks did it. From this, opera was born, and the plots of early operas were taken from Greek mythology (usually with the gods showing up to save the day at the end, which provided an opportunity for high-tech—for the 17th century—special effects).

The first great opera composer was Claudio Monteverdi. A few composers had written operas prior to his work, but not to the caliber or acclaim of Monteverdi’s. Early opera retold Greek stories; these thinkers and composers were looking to recreate the dramatic power of Greek theater, so what better source material than Greek stories? Monteverdi sets the story of Orpheus, the hero who must rescue his bride Euridice from the Underworld, defeating spirits with the power of his music.

For many years, Monteverdi worked for the Duke of Mantua in central Italy. There, he wrote Orfeo (1607), an opera based on the mythological character of Orpheus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In many ways, Orpheus was an ideal character for early opera (and indeed many early opera composers set his story): he was a musician who could charm with the playing of his harp not only forest animals but also figures from the underworld, from the river keeper Charon to the god of the underworld Hades. Orpheus’s story is a tragedy. He and Eurydice have fallen in love and will be married, and to celebrate, Eurydice and her friends head to the countryside where she is bitten by a snake and dies. Grieving but determined, Orpheus travels to the underworld to bring her back to the land of the living. Hades grants his permission on one condition: Orpheus shall lead Eurydice out of the underworld without looking back. He is not able to do this, and the two are separated for all eternity.

As the opera begins, the accompanying ensemble plays a “toccata” (“to touch,” or a fast instrumental piece). Generally, all operas begin with an instrumental work to set the tone of the opera. What do you think about this piece? Does it set the tone of a Greek hero about to rescue his bride from Hades?

Ex. 3.1: Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo, Toccata

In the Prologue to the opera, a figure representing music, La Musica, sets the stage and previews what will happen in the opera, how Orfeo will use the powers of music to battle the spirits of the Underworld. The form is strophic variation: the music varies, slightly, from one stanza to another. Note how the emotional and powerful singing is interspersed with the calm and elegant ritornello—or refrain—of the orchestra.

Ex. 3.2: Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo, “Vi ricorda o boschi ombrosi”

In nearly all opera works, there are two forms of monody: recitative, melody with speech-like rhythms, and aria, the main song. Generally, characters would sing recitative with a sparse basso continuo accompaniment to advance the plot, and the full orchestra would come in to introduce the aria, which conveyed the emotion of a particular moment. In this portion of the opera, the main character, Orfeo, is singing about how his love of Euridice has overshadowed his prior sadness. A ritornello, or recurring refrain, is played by the large ensemble between verses.

Opera spread in popularity from Italy across the European continent and eventually to England. There, Henry Purcell (organist at Westminster Abbey, the king’s Chapel Royal) staged works in London. Purcell was considered the greatest English-born composer through the nineteenth century. One of his most well-known operas, Dido and Aeneas, was originally written for a production at a local girls’ private school.

Ex. 3.3: Henry Purcell, Dido and Aeneas, “Thy Hand, Belinda”

Generally, recitative wasn’t a particularly memorable part of the opera; its musical role was to lead to the aria—a homophonic composition featuring a solo singer over the accompaniment. This example, however, is emotionally striking and sets the stage for a gorgeous aria. After Aeneas’ parting, Dido’s descending chromatic line paints a picture of tragedy as she laments to her servant Belinda.

Sacred Music in Mexico

As major European powers expanded their empire by conquering new parts of the world, their musical traditions followed. Francisco López Capillas (1608 – 1674) was a Mexican composer and organist who wrote in the European styles. Some records suggest he was born in Mexico City, and others that he was born in Andalusia, a southern community of the Spanish Peninsula. We do know he was a priest who performed in the cathedrals of Puebla and Mexico City, and he’s considered the first great Mexican composer of European-influenced art music. His compositions were sent to Spain, where they were archived.

Ex. 3.4: Francisco López Capillas, Canticle to the Virgin Mary for 4 voices

This piece shows López Capillas’s skill in the Renaissance polyphonic style, though it certainly fits the harmonic practices of the Baroque; brief segments of monophonic chant are followed by polyphonic voices. This piece also demonstrates the flexibility of how we identify time periods; while he composed during the first century of the Baroque period, he was celebrated for composing in the styles of the Renaissance.

Baroque Instrumental Music

During the Renaissance, most of the music that was published and purchased was vocal. Additionally, many of the instruments we heard from that era are no longer used frequently. However, during the Baroque, instrumental music began to outsell vocal music, and the violin—one of the instruments most associated with classical music—emerged. As instrumental music became more popular, composers wrote more idiomatically; they realized the strengths and weaknesses of each instrument and composed accordingly.

In this section, we’ll examine the instrumental works of Arcangelo Corelli, Johann Pachelbel, Antonio Vivaldi, and Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre.

The initial form of the symphony orchestra emerged during the Baroque. Stringed instruments—violin, viola, cello, and bass—were the backbone, and various wind and brass instruments were added – flute, oboe, bassoon, trumpets, and horns.

The Baroque orchestra also included the support of the basso continuo, often with a harpsichord—a keyboard instrument—playing chords and a low string instrument playing the bassline. Basso continuo emerged as a way to accompany these main melodic lines. Instrumentalists provided a relatively sparse accompaniment with a bass line and chords. While most of these instruments were used by future orchestral composers, the basso continuo (particularly, the harpsichord), disappeared as the Baroque period ended.

The concerto, a work for soloists, emerged during this increased writing of instrumental music. A solo concerto had one soloist playing against the full orchestra; a concerto grosso featured a small group of soloists (the concertino) playing against the full orchestra.

Arcangelo Corelli was an influential figure in the Baroque; with his music, the violin became an especially prominent instrument, the sonata (a multimovement work for an instrument) and concerto genres developed, and modern, functional harmony—the major and minor scales with certain chords usually moving from and to other chords to help drive the music—became the “standard.” While the Middle Ages and Renaissance saw a wide variety of different harmonies and scales, the music of the Baroque—the melodies, the chords, the bass lines—coalesced into two main scales: major and minor.

Ex. 3.5: Arcangelo Corelli, Christmas Concerto

In this concerto, the music alternates between the concertino—two violins and cello—and the rest of the strings and continuo.

Ex. 3.6: Johann Pachelbel, Canon in D major

Pachelbel is best known for this canon (a technique where a melody is repeated among different voices, parts, or instruments), though he wrote many instrumental works and taught one of the older brothers of Johann Sebastian Bach. This is most often heard at weddings today. For one reason, it’s lovely music. For another, it’s practical music for accompanying a processional; since the bass line and chord progressions are constantly repeating, musicians can convincingly bring this piece to a conclusion after each cycle of the chords and bass. Once the bride has arrived, the music can end.

As broad surfaces were filled with intricate detail in Baroque art and architecture, the steady bass and chords serve as pillars to support the soaring melodies.

About this performance: Kevin MacLeod is a composer who works with digital audio workstations. As technology has become more advanced, composers have access to digital instruments that are becoming increasingly realistic in sound.

Ex. 3.7: Antonio Vivaldi, Spring, first movement

Antonio Vivaldi, composer of The Four Seasons, played a major role in developing the concerto. He was ordained as a priest, but he also toured Europe to perform and wrote operas. His best-known position was as a music teacher at a school for orphaned girls, where he gave them a phenomenal music education. He wrote hundreds of concertos for his students. This work is ritornello form, a form that Vivaldi popularized; a recurring ritornello, or refrain, plays before and after each solo section. In these concertos, Vivaldi musically reflected a series of poems about each season.

Bonus Video: Vivaldi, The Four Seasons

The following video presents a nice summary of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons.

YouTube Video: “Why should you listen to Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons”? – Betsy Schwarm” by TED-Ed

You can read about two of Vivaldi’s students who became world-class musicians in this article:

Vivaldi’s lesser-known legacy: Female violin virtuosos of 18th century Venice

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre was a French composer who came from a family of musicians. She was a prodigy, showing remarkable skill at a young age, and while still a teenager, she became a court musician of King Louis XIV; most of her published compositions are dedicated to the king. She was a groundbreaking musician, publishing harpsichord music even while the instrument was not yet common in France, and being the first woman in France to compose an opera. She lived in an era where it was uncommon for women to work as professional musicians, and she was acclaimed for her musical talents.

Ex. 3.8: Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre, Trio Sonata No. 3 in D

This trio sonata is written for two violins and continuo. As you listen, note the melodic interplay between the two violins. The continuo is realized by instruments from the Baroque not common today: the viol da gamba playing the bass and the theorbo (similar to a lute) and the clavecin (a keyboard instrument) realizing the chords.

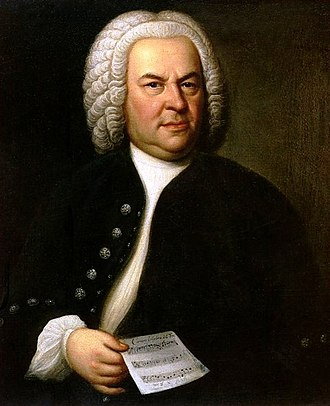

Johann Sebastian Bach

While monody, the expressive and ornamented melody with simple accompaniment, marked the beginning of the Baroque, polyphony reemerged as a defining feature of the Baroque’s last decades. This is especially seen in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, among the greatest contrapuntal (skilled at polyphony) minds of all time. He came from a family of musicians and taught himself music by consuming the music of other great composers, copying and studying their work. During his lifetime, many considered his compositions to be old-fashioned, but he was universally acknowledged as the greatest organ performer and improviser of his day.

During the seventeenth century, many families passed their trades down to the next generation so that future generations may continue to succeed in a vocation. This practice also held true for Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach was born into one of the largest musical families in Eisenach of the central German region known as Thuringia. He was orphaned at the young age of ten and raised by an older brother in Ohrdruf, Germany. Bach’s older brother was a church organist who prepared the young Johann for the family vocation. The Bach family, though great in number, were mostly of lower musical stature. Only a few of the Bachs had achieved the accomplished stature of court musicians, but the Bach family members were known and respected in the region. J.S. Bach also in turn taught four of his sons who later became leading composers for the next generation.

Bach received his first professional position at the age of eighteen in Arnstadt, Germany as a church organist. Bach’s first appointment was not a good philosophical match for the young aspiring musician. He felt his musical creativity and growth were being hindered and his innovation and originality unappreciated. The congregation seemed confused at times and felt the melody lost in Bach’s writings. He met and married his first wife while in Arnstadt, marrying Maria Barbara (possibly his cousin) in 1707. They had seven children together; two of their sons, Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Phillipp Emmanuel, became major composers for the next generation. Bach later was offered and accepted another position in Mühlhausen.

He continued to be offered positions that he accepted and so advanced in his professional position/title up to a court position in Weimer where he served nine years from 1708-1717. This position had a great number of responsibilities. Bach was required to write music for the Ducal church (the church of the duke that hired Bach), to perform as the church organist. In this position, Bach wrote organ music and sacred choral pieces for the choir in addition to writing sonatas and concertos (instrumental music) for court performances for his duke’s events. While at this post, Bach’s fame as an organist and the popularity of his organ works grew significantly.

Bach helped reinforce the popularity and potential of equal-tempered, or well-tempered tuning that has been the standard in Western music for centuries. To oversimplify the complex subject of tuning: using just intonation, or pure intonation, was a common way of tuning. Using physics, the notes of a single key or scale were as in tune as possible. However, the music sounded out of tune if the music changed key. With a twelve-tone equal temperament, the smallest interval is uniform throughout the octave. While individual chords within a key might not sound as rich as they would in just intonation (a subjective preference), equal temperament allows musicians to play in a wide variety of keys without retuning the instrument. Bach wrote The Well-Tempered Clavier, a set of preludes and fugues in every major and minor key.

Ex. 3.9: Johann Sebastian Bach, Prelude and Fugue in C Minor

The first half of this performance is a prelude; Bach takes the same short musical phrase and moves through different chords and keys. The second half of this performance is a fugue. Bach was a master of writing fugues, a polyphonic form. A fugue includes a subject, or main melody, that is played by each voice. Sections with the subject are interrupted by episodes, sections without the subject in its entirety, and that modulate from one key to another. The genius of polyphonic texture is that the composer is working with multiple melodies simultaneously. Instead of a melody being accompanied by chords or patterns, as we see in homophonic texture, the melodies are interwoven with more melodies.

Bonus Video: Bach’s Little Fugue in G minor

Want to listen to another Bach fugue? Watch this YouTube video of the piece with a graphic animated score of Bach’s Little Fugue in G minor.

YouTube Video: “Bach, “Little” Fugue in G minor, Organ” by smalin

With their multiple keyboards, plus a pedal board, organs are well suited to play fugues. This fugue is written for four voices. Two hands could play three of the voices while the feet could play the fourth voice. You can hear the subject played by a solo voice at the beginning, and as the exposition continues, each voice, from highest to lowest in pitch, plays the subject. A countersubject—another prominent melody—often accompanies the subject. Compared to the rest of this piece, the exposition is long. Clocking in at over a minute, it lasts for approximately 25% of the piece. The work then alternates between sections with the subject and the episodes, most of which last for 10-20 seconds—a noticeably shorter duration.

Bach wrote for every instrument and every genre (except opera) during his lifetime. He was also very active in sacred music and is especially known for his role as cantor at the St. Thomas church in Leipzig. He was responsible for music at four different churches, plus funerals and ceremonies, and composed a half hour of new music for every Sunday service and church holiday.

Bach later became blind but continued composing by dictating to his children. He had also already begun to organize his compositions into orderly sets of organ chorale preludes, preludes and fugues for harpsichord, and organ fugues. He started to outline and recapitulate his conclusive thoughts about Baroque music, forms, performance, composition, fugal techniques, and genres. This knowledge and innovation appears in such works as The Art of Fugue—a collection of fugues all utilizing the same subject left incomplete due to his death—the thirty-three Goldberg Variations for harpsichord, and the Mass in B minor.

Bach was an intrinsically motivated composer who composed music for himself and a small group of students and close friends. This type of composition was a break from the previous norms of composers. Even after his death, Bach’s music was ignored by the musical public. It was, however, appreciated and admired by future great composers such as Mozart and Beethoven.

Ex. 3.10: Johann Sebastian Bach, Mass in B Minor, “Dona nobis pacem”

Bach wrote his Mass in B Minor a year before he died. The Mass closes as voices and instruments use polyphonic texture with the recurring phrase “Dona nobis pacem,” Latin for “Give us peace.”

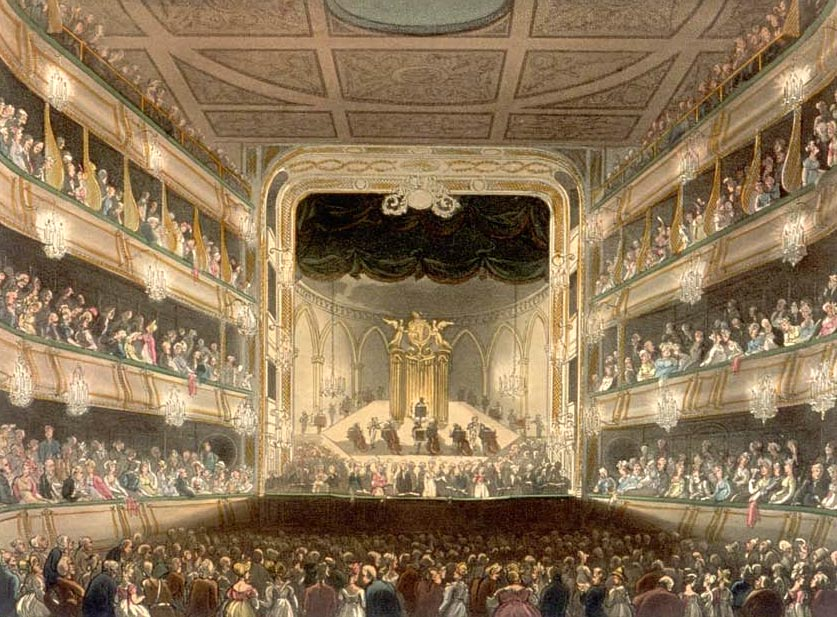

George Frideric Handel

Bach had a tremendous amount of respect for the other great composer of the late Baroque, George Frideric Handel. “He is the only person I would wish to see before I die, and the only person I would wish to be, were I not Bach.” The two were both born in 1685 in central Germany. They saw the same eye doctor in old age and both went blind from his procedures. While Bach stayed in Germany and focused on court and church music, Handel traveled Europe and found success in theater.

Handel’s father was an attorney and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, but Handel decided that he wanted to be a musician instead. With the help of a local nobleman, he persuaded his father to agree. After learning the basics of composition, Handel journeyed to Italy to learn to write opera. Italy, after all, was the home of opera, and opera was

the most popular musical entertainment of the day. After writing a few operas, he took a job in London, England, where Italian opera was very much the rage, eventually establishing his own opera company and producing scores of Italian operas, which were initially very well received by the English public.

Handel made his career in London. The English monarchy often hired Handel to compose music for special occasions, including the Coronation Anthems, Music for the Royal Fireworks, and Water Music. Water Music was written for an event along the river Thames, where Parliament lords along with the lower class could hear Handel’s music as the king proceeded with his court and fifty-some boats of musicians along the river.

Ex. 3.11: George Frideric Handel, Water Music, Hornpipe

Water Music is a dance suite. However, this was music to be listened to, using forms from dance music that had particular rhythms, tempos, and moods. This movement, Hornpipe, is named for a dance from the British Isles.

Bonus Video: Handel, Water Music

You can watch performers using Baroque instruments in this video:

YouTube Video: “Handel Water Music: Hornpipe; the FestspielOrchester Göttingen, Laurence Cummings, director 4K” by Voices of Music

While Handel had the opportunity to write for kings and queens in England, he originally went to make money producing Italian opera. He wrote opera seria—serious opera—which were three long acts with stories about emperors or gods, appealing to the upper class. Julius Caesar was his greatest success and best-known opera today. But, opera was financially risky, and Italian opera in England imploded. Several English opera companies each competed for the public’s business. The divas who sang the main roles, and whom the public bought their tickets to see, demanded high salaries. In 1728, a librettist—the person who wrote the lyrics, or libretto—named John Gay and a composer named Johann Pepusch premiered a new sort of opera in London called ballad opera. It was sung entirely in English and its music was based on folk tunes known by most inhabitants of the British Isles. For the English public, the majority of whom had been attending Italian opera without understanding the language in which it was sung, English language opera was a big hit. Both Handel’s opera company and his competitors fought for financial stability, and Handel had to find other ways to make a profit. He hit on the idea of writing English oratorio.

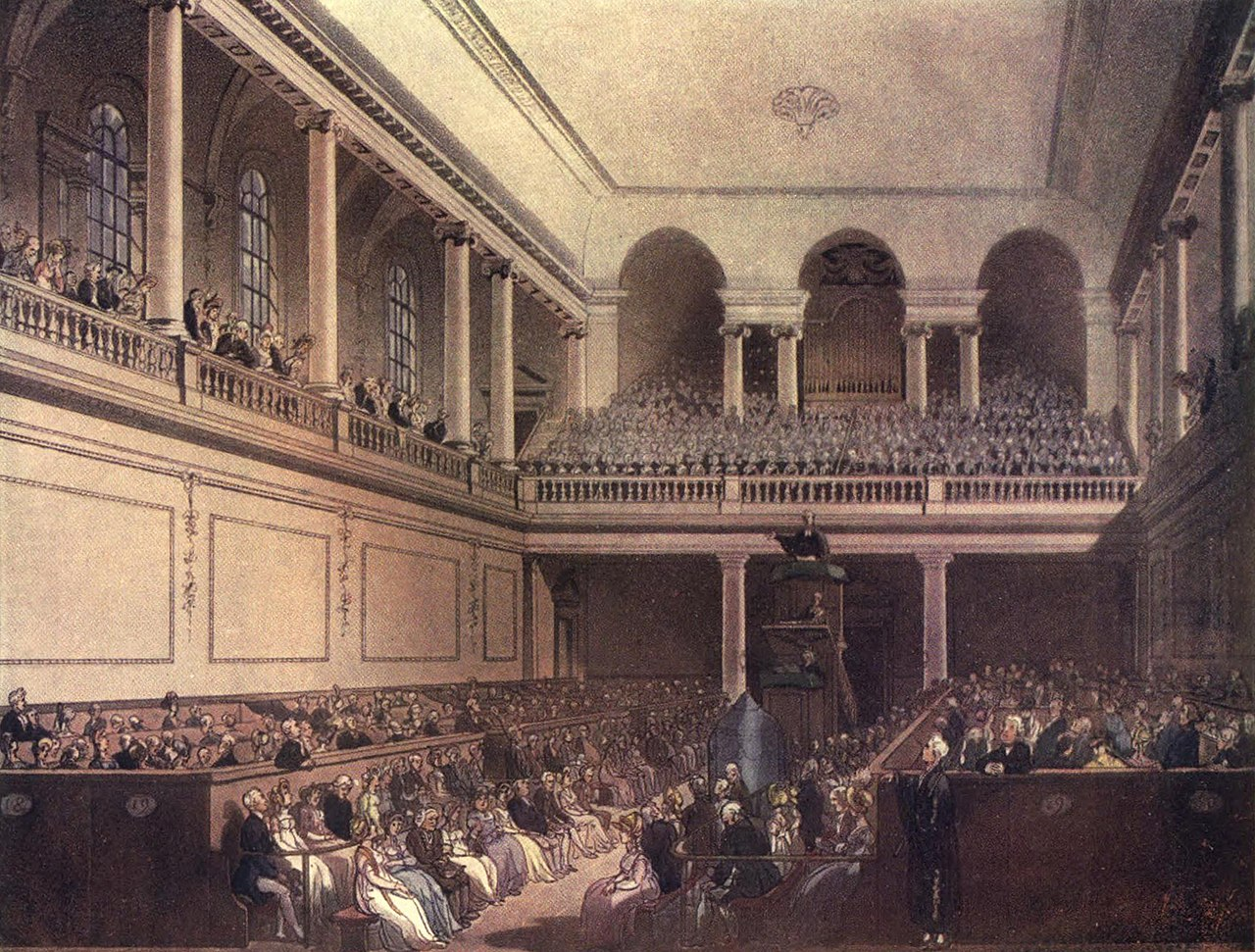

Oratorio is something like a sacred opera that is not staged. Like operas, they are relatively long works, often spanning over two hours when performed in entirety. Like opera, oratorios are entirely sung to orchestral accompaniment. They feature recitatives, arias, and choruses, just like opera. Most oratorios also tell the story of an important character from the Christian Bible. But, oratorios are not acted out. Historically speaking, this is the reason that they exist. During the Baroque period at sacred times in the Christian church year, such as Lent, stage entertainment was prohibited. The idea was that during Lent, individuals should be looking inward and preparing themselves for the death and resurrection of Christ, and attending plays and operas would distract from that. Nevertheless, individuals still wanted entertainment, hence, oratorios. These oratorios would be performed as concerts, not in the church, but because they were not acted out they were perceived as not having a “detrimental” effect on the spiritual lives of those in the audience. The first oratorios were performed in Italy; then they spread elsewhere on the continent and to England.

Handel realized how powerful English ballad opera had been for the general population and started writing oratorios in the English language. He used the same music styles as he had in his operas, only including more choruses. In no time at all, his oratorios were being lauded as some of the most popular performances in London.

Handel is most remembered for his oratorio Messiah which was first performed in 1741. It focuses on the prophecies and life of Jesus, along with his victory over death. It was written for a benefit concert to be held in Dublin, Ireland. Atypically, his librettist took the words for the oratorio straight from the King James Bible instead of putting the story into his own words. Once in Ireland, Handel assembled solo singers as well as a chorus of musical amateurs to sing the many choruses he wrote for the oratorio. There, it was popular, if not controversial. One of the soloists was a woman who was a famous actress. Some critics remarked that it was inappropriate for a woman who normally performed on the stage to be singing words from sacred scripture. Others objected to sacred scripture being sung in a concert instead of in church. Perhaps influenced by these opinions, Messiah was performed only a few times during the 1740s. Since the end of the eighteenth century, however, it has been performed more than almost any other composition of classical music. While these issues may not seem controversial to us today, they remind us that people throughout history have disagreed about how sacred texts should be used and about what sort of music should be used to set them.

Ex. 3.12: George Frideric Handel, “Hallelujah” Chorus

The “Hallelujah” Chorus from Handel’s Messiah alternates between monophonic, homophonic, and polyphonic textures.

Bonus Video: Handel, “Hallelujah Chorus”

You can watch this video of Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus. The different parts are visually color-coded in the video, allowing you to both hear and see how the different textures occur.

YouTube Video: “Handel, Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah (with scrolling bar-graph score)” by smalin

Handel’s Messiah has many sections. Other well-loved favorites from the Messiah include “For Unto Us a Child Is Born,” “Comfort Ye My People,” “Surely He Hath Borne Our Griefs,” “Behold, a Virgin shall conceive,” “O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion,” and “The Trumpet Shall Sound.”

Bonus Video: Handel’s Messiah: A Soulful Celebration

Handel’s Messiah has inspired musicians in the centuries since its original performance. This 1991 Gospel arrangement was part of Handel’s Messiah: A Soulful Celebration, winner of the 1992 Grammy for Best Contemporary Soul Gospel Album.

YouTube Video: “Joyful Celebration – Hallelujah Handel’s Messiah – HD” by Victory Videos-180-The Zone-UndergroundZone

Meanwhile, Throughout the World

Most of the surviving records of Western music document trends and histories in Europe. A brief sample of other music throughout the world during these time periods include:

1612 – Henry Ainsworth publishes The Book of Psalmes: Englished Both in Prose and Metre; this would be used by the Pilgrims who would colonize New England.

1698 – The first printed music in the future United States appears in the ninth edition of the Bay Psalm Book

18th Century – Sichuan opera develops in China. Older opera-style melodies fused with Sichuan customs.

Throughout the Baroque period, various forms of indigenous music from around the world fused with the musical styles of conquering colonial empires. Some indigenous styles survive, but others disappear.

Attributions

This chapter was adapted from Understanding Music: Past and Present by N. Alan Clark, Thomas Heflin, Jeffrey Kluball, and Elizabeth Kramer from the University System of Georgia, licensed by a CC BY-SA 4.0 international license.

Continuous realization of harmony throughout a musical piece, usually by a harpsichord and/or cello. The Basso continuo provides a framework/template for harmonic accompaniments.

Different sections of a piece of music having a set volume unique for that particular section.

A style of sung music with a solo voice accompanied by instruments, particularly related to the development of opera in seventeenth-century Italy.

A staged musical drama for voices and orchestra. Operas are fully blocked and performed in costume with sets. Operas utilize arias and recitatives without narration.

Instrumental piece, meaning “to touch” in Italian. Generally involves fast or technically impressive passages.

Slight variations from one stanza to another.

Repeated unifying sections found in between the solo sections of a concerto grosso.

An operatic number using speech-like melodies and rhythms, performed using a flexible tempo, to sparse accompaniment, most often provided by the basso continuo. Recitatives are often performed between arias and have texts that tend to be descriptive and narrating.

Homophonic compositions featuring a solo singer over the accompaniment. Arias are very melodic and primarily utilized in operas, cantatas, and oratorios.

Music that is well-suited for a particular instrument or voice.

A composition for a soloist or a group of soloists and an orchestra, generally in three movements with fast, slow, and fast tempos, respectively.

A musical composition for a small group of soloists and orchestra.

A small group of soloists in a concerto grosso.

Composition for a solo instrument or an instrument with piano accompaniment, generally in multiple movements with contrasting tempos.

Polyphonic treatment of melody that harmonizes a melody with a variation of itself.

Someone who, as a child, creates an output of work or ability comparable in quality to an adult expert.

Tuning by dividing the octave into equal parts.

Form written in an imitative contrapuntal style in multiple parts. Fugues are based on their original tune, which is called the subject. The subject is then imitated and overlapped by the other parts called the answer, countersubject, stretto, and episode.

A person who writes the libretto, the text or actual words of an opera, musical, cantata, or oratorio.

A major work with religious or contemplative characters for solo voices, chorus, and orchestra. Oratorios do not utilize blocking, costumes, or scenery.