29 Latine America: Foreigners in their Native Land

U.S. History with a Spanish Accent

In his wonderfully thought-provoking book, Our America, Felipe Fernández-Armesto upends the standard Anglo-American account of U.S. history, which imagines the country as originating with the founding of the English colonies of Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth (1620), and which treats the subsequent history of the country as if it unfolded from east to west.[1] Fernández-Armesto rotates the picture to tell the story of the country as it unfolded from south to north. In this telling, the United States’ colonial origins are as much Spanish as they are English, and the descendants of the first Latine Americans have as much reason to count their ancestors among the nation’s founders as does any Anglo descendant of a Virginia planter or a New England Pilgrim.

Fernández-Armesto’s “Hispanic-accented account,” helps us see “today’s plural America” as the product of “the whole of America’s past, not a threat to traditional U.S. identity.” His alternative narrative intersects with the Anglo narrative while highlighting an argument that there is “no single frontier, no single language, or tradition, or identity, no manifest destiny, no culture that deserves to be hegemonic or that predominates or ought to predominate by virtue of U.S. historic experience” (Fernández-Armesto, 2014: xxviii).

Early Spanish Settlements in (Future) U.S. Territory

Founded over a hundred years before Jamestown, Puerto Rico was the first Spanish colony in what today is a U.S. territory. In 1508, Spanish explorer and conquistador, Juan Ponce de León founded a settlement at Caparra in Puerto Rico. Caparra was abandoned in 1521, but the city of San Juan, barely 8 miles away, replaced it as the capital of Puerto Rico, making San Juan the oldest continuously inhabited European city in the United States.[2]

Nobody thinks of Puerto Rico as the place where U.S. history began. That might be, in part, because the island of Puerto Rico became a U.S. possession only after the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898. It then became a U.S. territory after the passage of the Jones-Shafroth Act in 1917, which also granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship.Yet today, their fellow citizens in the 50 states too often forget the fact that anyone born in Puerto Rico is a U.S. citizen.

Putting Puerto Rico aside, the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the continental United States is San Agustín (Saint Augustine), Florida. Founded by the Spanish in 1565, it remained a Spanish city until 1819, when Spain ceded Florida to the United States.

Another settlement in the United States with a Spanish heritage almost as old, if not older than Jamestown, is Santa Fe, New Mexico. The area was already under Spanish control in 1598, even if the city of Santa Fe proper was not established until 1610, three years after Jamestown (Weber 2009: 57-59). This makes Santa Fe the oldest continuously inhabited state or territorial capital in the continental United States.

The Terms Hispanic and Latine

Before continuing, it might be a good idea to briefly discuss the terms Hispanic and Latine. Just as the term Indian is a problematic way to refer to America’s Indigenous people, who, as discussed in Chapter 27, do not represent a monolithic group, the term Hispanic obscures much about the diversity of American people to whom that label could apply.

In fact, prior to the 1970s, the overwhelming majority of Americans that would come to be regarded as Hispanic were of either Mexican, Puerto Rican, or Cuban descent, and that is how they tended to identify. The idea that they all belonged to one, unified panethnic group with overlapping concerns never occurred to them. The drive to construct a panethnic Hispanic identity only began to take shape in the 1970s as civil rights activists, government agencies, and Spanish-language media executives, each with their own particular interests in mind, promoted the idea of an American Hispanic community animated by shared interests (Mora 2014).

Without getting into too much detail on the historical and sociological reasons for the emergence of the term Hispanic, suffice it to say that after its introduction in the decennial census in 1980, the term spread rapidly throughout academia during the 1980s (Mora 2014: 161). Meanwhile, a competing term, Latino/Latina, became increasingly popular in grassroots movements and among community activists. While the term Hispanic, which emphasized Spanish heritage and language, tended to strike activists as too conservative, the term Latino/Latina seemed better aligned with their New World identities and better suited to their progressive critiques of colonialism and the struggle to undo it.

In current discourse, the gender-neutral term Latine is preferred, and it’s important to note that Hispanic and Latine are not interchangeable. As Lola Méndez writes (2023):

“Hispanic and Latino are increasingly seen as outdated terms to refer to people of Latin American heritage for several reasons. Hispanic is often insulting to many people of Latin American heritage, as it centers the heritage of the colonial powers responsible for the slaughter of Latin America’s 56 million Indigenous people during the largest genocide in history.

Latino, on the other hand, refers to everyone from Latin America. Like other romance languages, the Spanish language traditionally uses the masculine configuration of words to refer to a group of people. The -o and -a endings of nouns and adjectives in the Spanish language are masculine and feminine, respectively, which the queer and trans community especially have pointed out as not inclusive to all genders.”

As with all labels connected to cherished identities, individuals tend to embrace different labels for their own particular reasons, and it’s always best to ask people what term(s) they prefer.

Demographics of Latine America Today

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, Latines constitute the largest minoritized group in the United States. Just over sixty-two million people (or 19% of the U.S. population) self-identified as Latine in the census (though the census still uses the outdated term “Hispanic”). Among all Latines, people of Mexican origin numbered over thirty-seven million, accounting for nearly 62% of the U.S. Latine population. People of Puerto Rican heritage constituted the second largest group at about 5.8 million. And the next six largest Latine origin groups were Cubans, Salvadorans, Dominicans, Guatemalans, Colombians and Hondurans (Funk & Lopez 2022).

Because the issue of immigration is continually in the news—with the U.S.–Mexico border often in the spotlight—some non-Latines may be under the impression that most Latines are immigrants and undocumented. In fact the vast majority of all Latines, roughly 80%, are U.S. citizens, either by birth (67%), or naturalization (13%). The other 20% are non-citizens, some of whom are legal residents and others of whom are undocumented (US Census Bureau 2022).

Of course, the number of Latines living in the U.S. who were not born in the U.S. but who immigrated from elsewhere is also not insignificant. In 2020, foreign-born Latines, i.e., naturalized citizens and non-citizens taken together, accounted for about one-third of the U.S. Latine population, or roughly twenty million people. But again, just to emphasize the point, the vast majority of Latines living in the United States are U.S. citizens (Moslimani & Noe-Bustamante 2023).

The Mexican Diaspora

While the title of this chapter is “Latine America,” exhaustively covering all of Latine America is outside the scope of this chapter (and course). Instead, the rest of the chapter is devoted to the story of the largest segment of the U.S. Latine population, people of Mexican descent, who, as noted above, comprise 62% of the Latine population within the U.S. population, 80% of whom are US citizens.

The Spanish Conquest of Mexico

The history of the United States is inextricably linked to that of its southern neighbor, Mexico. Like the United States, Mexico began as a European colony. What today we call Mexico was forcibly taken from Indigenous people, while the people themselves were murdered, marginalized, or absorbed through intermarriage with the conquerors. Later, Mexico, like the United States, separated from its conqueror by means of armed rebellion. In this chapter, we will explore briefly how lands once controlled by Indigenous peoples became colonies of Spain, then sovereign Mexican states, and finally, in some places, U.S. territories and eventually U.S. states.

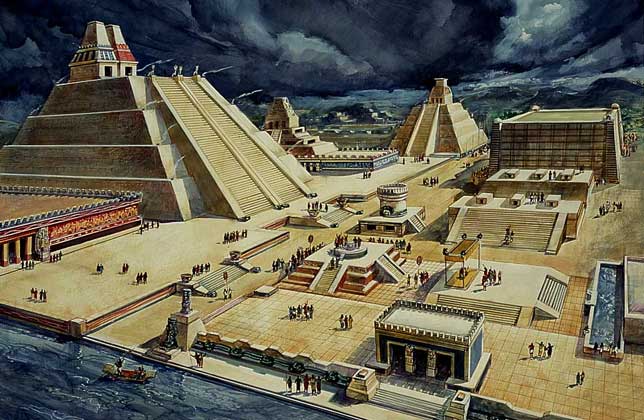

In 1519, two years before the founding of San Juan (Puerto Rico), the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés sailed from Cuba to the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. His intention was to conquer the Aztec empire centered in Tenochtitlan (the site of modern-day Mexico City). With a population of perhaps 200,000, Tenochtitlan was undoubtedly the largest city in the New World. It may have been five times the size of London at the time and was rivaled only by European cities like Paris and Venice. At any rate, it was by Cortés’ own account, a fabulous city.

…

When Cortés reached Tenochtitlan, the Aztec emperor Montezuma recognized the formidable advantage of the Spanish, with their metal weapons, crossbows, and cannons, backed by an army of thousands of Indigenous Aztec enemies, and was unwilling to start a war he was sure to lose. Instead, he sought to buy the invaders off and perhaps stall for time (Townsend 2019: 10; 94–116).

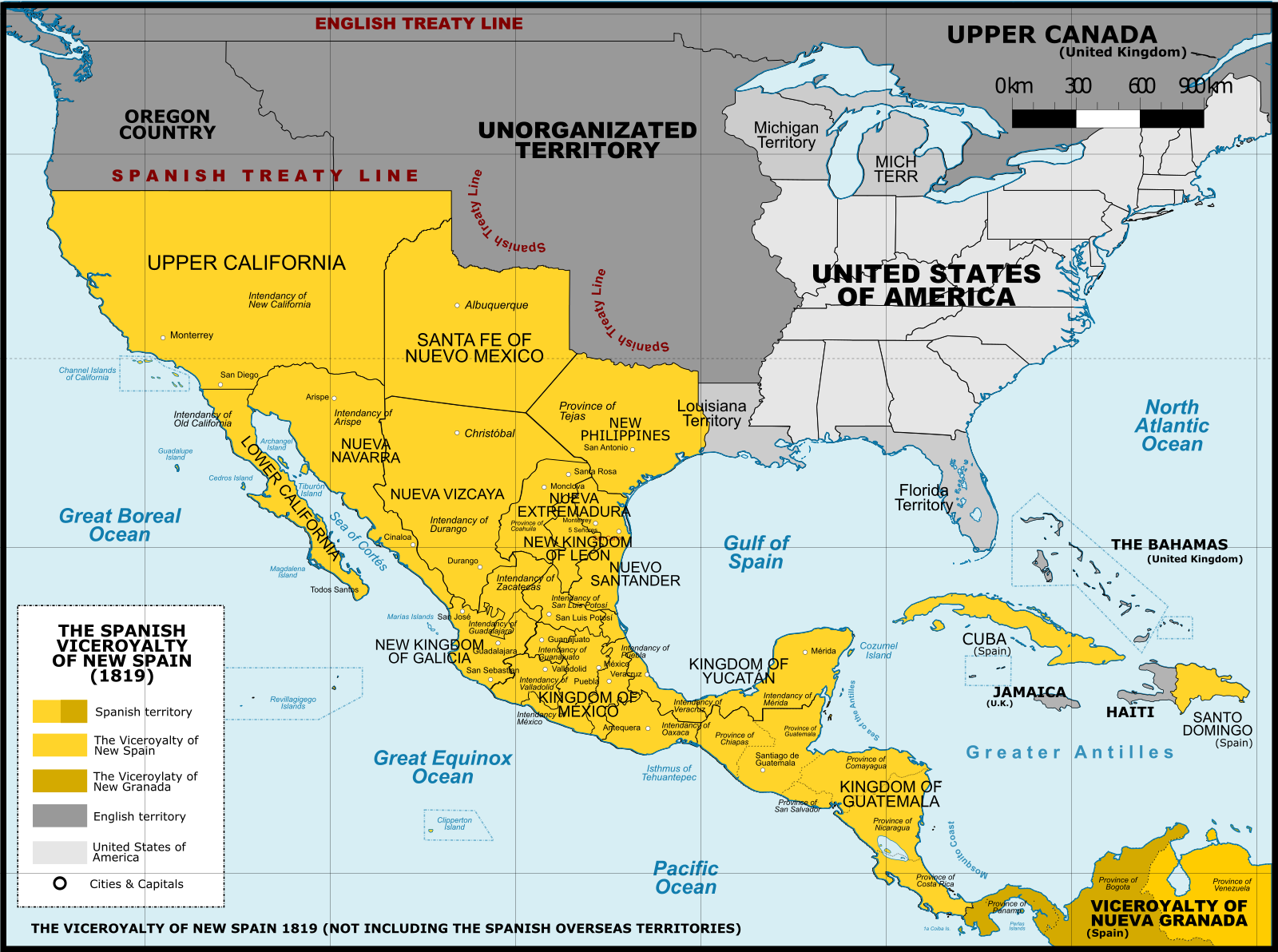

In the end, Montezuma failed. He was killed; war broke out, as did a deadly smallpox epidemic, which further weakened the Aztecs, and ultimately, Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish invaders in 1521. Tenochtitlan, now in ruins, would eventually become Mexico City, the capital and base for further exploration and conquest of a vast territory that became known as the Kingdom of New Spain under the direct control of the Spanish Crown (Russell 2019: 68).

The Kingdom of New Spain

In the earliest years of the kingdom, conquistadors like Cortés sought to maintain and enrich themselves by exploiting these Indigenous communities through the encomienda system. The encomienda was a Spanish legal institution by which the king rewarded those who had risked their lives in frontier warfare by granting them the right to collect tribute from the native population. In return, the recipient of the encomienda (the encomendero) was supposed to assume responsibility for protecting and Christianizing the Indians (Weber 2009: 92–94).

Later, the Crown abolished the encomienda system for fear that it was creating a politically influential, wealthy class that abused the Indigenous peoples whom the king considered his subjects. The encomienda system was replaced with the repartimiento, a system that required native men to perform periodic work considered essential for the public good. Participation in the repartimiento was compulsory, and the system was often abused in ways that amounted to little more than slavery by a different name (Kirkwood 2005).

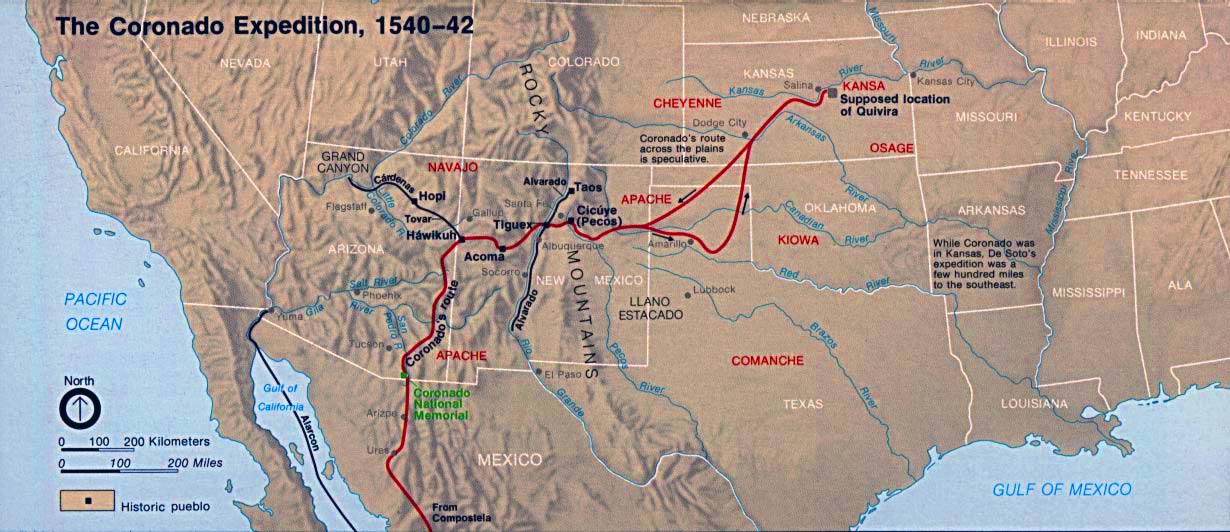

In the meantime, restless conquistadors, attracted by fantastic stories of fabulously rich cities in the north, went looking for them. One such explorer was Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, who led an expedition in 1540 in search of the Cities of Cîbola, often referred to today as the mythical Seven Cities of Gold. Instead, Coronado found the sunbaked, mud-brick apartments of a modest town of Zuni people (Weber 2009: 14). The search for Quivira, another supposed city of gold, only led into the vast plains of Kansas (Weber 2009: 39).

While Coronado never found what he was looking for, his expedition ranged over eastern Arizona, northern New Mexico, and the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma and into northeastern Kansas. In the 1500s, these lands were all claimed by New Spain. Three centuries later, they would become a contested frontier, over which Mexico, after gaining its independence from Spain, would go to war with the United States.

As for settling the far north, the first serious attempt was in 1598 when Juan de Oñate was commissioned by the Spanish Crown to explore and colonize it. Oñate led about six– or seven–hundred settlers into New Mexico and established a number of settlements, including the precursors of present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico, and El Paso, Texas. Of course, as in most cases of European encroachment on Indigenous lands, the colonizers were not welcome. Oñate himself is infamous for his brutal dealings with the native people, which set the stage for a situation that would endure for three centuries. Natives and settlers alike greatly feared and mistrusted each other, and the settlers would maintain themselves by violent means, even as natives found ways to adapt to their presence. Moreover, the isolation of the far north by hundreds of miles from the closest settlements in northern New Spain would keep the settlements from growing very quickly so that throughout the 1600s, the Spanish population in New Mexico was probably never larger than three thousand. Nevertheless, this population was large enough to transform the character of the nearby land and Indigenous people, at the same time that the land and Indigenous people transformed the settlers (Weber 2009: 67–68).

…

Mexican Independence

Settlement of the northern frontiers proceeded slowly throughout the 1700s. As the early 1800s got underway, many Mexicans found themselves disenchanted with Spanish rule, and in 1810, a Catholic priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla launched an unsuccessful crusade for Mexican independence. Although Hidalgo was captured and executed, insurgents kept the independence movement alive until 1821, when an army officer named Agustín de Iturbide finally succeeded in conducting a bloodless coup, making Mexico an independent country. Now just as all of this was happening in Mexico, the United States was on the verge of a major era of empire building.

U.S. Annexation of Mexican Land

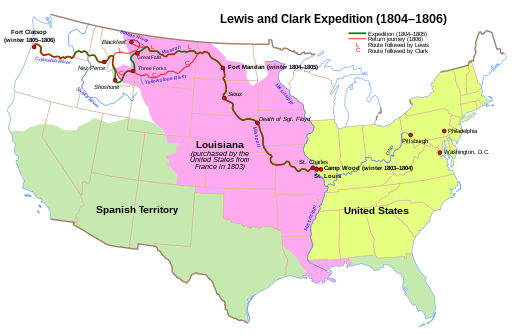

By the early 19th century, New Spain had been exploring the North American continent for three centuries already, while the United States was only just beginning to probe its western frontier. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson purchased the so-called Louisiana territory formerly claimed by France, virtually doubling U.S. land area overnight. The following year, Jefferson commissioned Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore and map the newly purchased territory (a mission they could not have completed without the guidance and expertise of Lemhi Shoshone woman Sacagawea). The Lewis and Clark expedition left Missouri in 1804, reached the Pacific Ocean on the coast of Oregon in 1805, and returned in 1806 with their reports of the vast territories of the Great Plains and the Northwest.

The opening of the Louisiana Territory to Anglo settlement put Anglo Americans in closer proximity to Spanish Territory. Then in the 1820s, Anglos began pouring across the Mexican border and settling in the territory then known as Tejas (Texas). Many of the newcomers were southern U.S. slaveholders eager to find new lands for their lucrative cotton growing enterprise. Alarmed, the Mexican government sent a commission to investigate (Takaki 2008: 156). A Mexican army officer of the day described the situation this way:

The Americans from the north have taken possession of practically all the eastern part of Texas, in most cases without the permission of the authorities. They immigrate constantly, finding no one to prevent them, and take possession of the sitio [location] that best suits them without either asking leave or going through any formality other than that of building their homes.

In 1830, the Mexican government outlawed slavery and prohibited continued American immigration. The Americans continued to cross the border in defiance of Mexican law. By 1835, there were about twenty thousand Anglos in Texas compared to only four thousand Mexicans. Men like Stephen Austin began agitating for an American takeover of Texas (Takaki 2008: 156–157), characterizing the conflict in racist terms as “a war of barbarism and of despotic principles, waged by the mongrel Spanish-Indian and Negro race, against civilization and the Anglo-American race” (Weber 2009: 245–246).

In 1836, there was a revolt in Texas, known as the Texas Revolution, when 175 Texas rebels launched an armed insurrection in San Antonio. The rebels included both Anglo-Texans and Tejanos, Mexican citizens, who had begun to identify with Texas as their homeland quite apart from Mexico. In other words, the Tejanos and the Anglo-Texans shared a similar desire to be free from the dictates of a centralist Mexican government in faraway Mexico City. When the Texans declared Texas to be an independent republic, the Mexican president and general Antonio López de Santa Anna brought an army to Texas to put down the revolt. On February 23, Santa Anna confronted the rebels in San Antonio where the rebels barricaded themselves inside the Alamo, a Catholic mission turned military fort. The rebels refused to surrender and fought to the death against the Mexican army after a 13-day siege. Santa Anna went on to capture the town of Goliad where he slaughtered 400 American prisoners. The American Sam Houston mounted a counterattack, surprising Santa Anna’s army at San Jacinto and slaughtering 630 Mexican soldiers (Takaki 2008: 157). These events basically established Texas as an independent republic although Mexico refused to acknowledge it as such.

At this point, it may be important to remind readers of a common American misconception. Americans, if they know anything at all about the Alamo, sometimes operate under the false narrative that Santa Anna attacked the United States and that the defenders of the Alamo were patriots defending their country against a foreign invader. The Alamo was in fact in Mexican territory, and Santa Anna’s intent was to put down a rebellion taking place in Mexico. It is also important to note that among the Anglo defenders of the Alamo were Tejanos, Mexican citizens who had begun to identify with Texas as their homeland quite apart from either Mexico or the United States. In other words, the Tejanos and the Anglo-Texans shared some sympathies with respect to their view of the Texas territory.

Texas remained a de facto independent republic until 1845 when the U.S. government, which also had an eye on gaining control of California, formally annexed Texas, thus starting a war with Mexico that would last for two years. The U.S. ultimately defeated Mexico, and when the war ended in 1848, with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States had taken practically the entirety of the American Southwest, including present-day California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas (and of course everything else further north that may have once been Mexican territory).

Foreigners in Their Native Land

Suddenly thousands of Mexicans found themselves inside the United States. They had not crossed over any border, rather the border had crossed over them. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave Mexicans living in the conquered territory the choice of either leaving within one year or becoming American citizens. Most Mexicans, seeing very little difference between one government and another, chose to stay in their established homes. They saw no reason why the frontier, which had always been insulated from the levers of government, would not continue to be relatively free. Now, a people whose ancestors had first been Spanish subjects and later Mexican citizens became United States citizens (Samora et al. 1993: 100).

* * *

Although the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had guaranteed to Mexican people living in the southwestern territories “the enjoyment of all the rights of citizens of the United States according to the principles of the Constitution” (Takaki 2008: 164), it would be disingenuous to pretend that Anglos regarded Mexicans as their equals. … Mexicans living on the frontier were often confronted with outright violence. Anglo newcomers ran Mexican ranchers off their lands in Texas and drove Mexicans out of towns in Texas and Arizona. During the California Gold Rush, which had attracted men from all over the world and from as far away as China, the Anglos, who outnumbered other groups, often harassed the Spanish-speaking miners as well as the Chinese. California was notorious for passing discriminatory laws, just one example of which was the Foreign-Miners Tax of 1850, which required any miner who was not an American citizen to pay heavier taxes on the yields from their mines (Samora et al. 1993: 107–117). To Mexicans who were treated as foreign miners despite having gained citizenship as a provision of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, this was obviously an outrage.

…

By the 1880s, the character of the Southwest was beginning to change. Whites had largely “consolidated their political and economic hold on the region,” and with that all the latest elements of a national mainstream culture had begun to appear, from consumer products to fashion.

The changing cultural landscape also helped shape Mexican Americans’ sense of their own identities in diverse ways. Some Mexican Americans still idealized Mexico as the beloved homeland and continued to see themselves as Mexican through and through. They tended to reject Americanization as a process that would produce a community that was “neither Mexican nor American but a corruption of both heritages.” Others claimed the United States as their only home but embraced a bi-cultural identity. They recognized the practicality of learning English, while advocating for the preservation of Spanish through programs such as bilingual education in public schools.

Mexican Labor Builds a New Southwest

Between 1880 and 1920, the Southwest underwent a radical economic transformation, becoming a center of extractive industries such as mining and agriculture, both of which required large inputs of labor. The growth in these enterprises was made possible by the extension of transcontinental railroad networks into all regions of the United States, allowing for the distribution of raw materials and agricultural products to every corner of the United States. Mexico too embarked on railroad building, connecting Mexico City with the border states of northern Mexico.

Mexican labor was indispensable to the booming economic development of the late 19th century Southwest. “Mexican labor built, maintained, and repaired the railroads that forged the links between the Southwest and the urban markets of the Midwest and the East. … Mexican labor also made agricultural expansion in the Southwest possible.” Mexican workers cleared land and harvested cotton in Texas, planted and harvested sugar beets in the Great Plains, and harvested citrus in California. Forty percent of the fruits and vegetables produced in the American Southwest was accomplished largely thanks to Mexican labor. In addition, the region’s “mines and smelters, … government irrigation projects, road construction, cement factories, and municipal rail work all depended on Mexican labor” (Vargas 2017: 168–169).

Northward into the 20th Century

From 1900 through the Great Depression

Robust migration from Mexico to the United States continued into the early 20th century. Approximately 219,000 Mexicans migrated to the U.S. between 1910 and 1920. As a result, the Spanish-speaking populations of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas doubled in size, while that of California quadrupled in size! (Vargas 2017: 177). Several factors prompted Mexicans to migrate to the U.S. during these years in previously unprecedented numbers. For one thing, Anglo-American investment in Mexico’s infrastructure destabilized the Mexican economy, destroying the livelihoods of Mexican laborers who were engaged in traditional urban occupations and forcing others off of communal lands. Secondly, the Mexican Revolution, a civil war characterized by a series of regional armed conflicts, lasting from 1910 to 1920, caused many Mexicans to flee the chaos and violence (De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 86).

The outbreak of World War I (1914–1918) also enticed Mexicans to migrate to the U.S. as the supply of immigrant labor from Europe was cut off, creating widespread labor shortages. In response, Mexicans fanned out across the country to provide labor wherever it was needed. When the U.S. entered the war belatedly in 1917, Mexicans helped supply the increased labor associated with the war industries.

The 1920s, or so-called Roaring Twenties after World War I, were years of prosperity and economic expansion, but the “good times” ended abruptly in 1929 when the stock market crashed, followed by the Great Depression which lasted for about a decade. The Great Depression brought hard times to almost everybody. But Mexicans and Mexican Americans were particularly hard hit. The need for labor dried up almost overnight and millions of people found themselves jobless during the 1930s. As the government enacted its first modest attempts at providing economic relief for the unemployed, public officials “throughout the Southwest and in such cities as Gary, Indiana; Detroit, Michigan; Toledo, Ohio, where there were large concentrations of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, … decided that it would be cheaper to send the Mexican[s] … back to Mexico,” rather than to provide them the same economic support as everyone else. “Thus, a system of repatriation began” (Samora et al. 1993: 136–137). Samora and colleagues’ extended description captures the cruelty and injustice of the system:

During the first four years of the 1930s, well over four hundred thousand Mexicans were repatriated to Mexico. Most of those repatriated Mexican citizens were legal residents of the United States; many were American citizens that is, Mexican Americans. Some had lived in this country thirty or forty years and had established their homes and their roots here. Many families were broken up, for in some cases either the father or mother, or both, were alien [sic], but the children, having been born and raised in this country, were American citizens and allowed to stay while their parents were repatriated. To be sure, some Mexican aliens departed voluntarily, but those who were forcibly removed and those whose families were disrupted suffered enormous hardships during this period (Samora et al. 1993: 137).

World War II Era

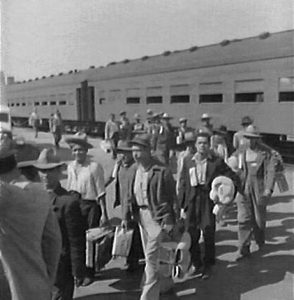

Significant immigration from Mexico did not resume again until the 1940s when the outbreak of World War II created economic conditions similar to those that had existed during World War I. The need for men to fight in the war and the need for workers in the war industries had drawn many laborers away from other essential work, in particular farm work. To address the farm labor shortage, the U.S. once again sought to import labor from Mexico. However, remembering the deportations of Mexicans from the U.S. in the 1930s and mindful, too, of the discriminatory tendencies of some U.S. states, the Mexican government insisted on negotiating worker protections around issues such as health care, wages, housing, food, and the number of working hours, as well as extracting assurances protecting Mexican nationals against discrimination. Understood to be part of Mexico’s contribution to the war effort, the so-called Bracero agreement was supposed to be primarily a temporary farm worker program although some braceros also worked on the railroads (Samora et al. 1993: 137–139).

More than 200,000 Mexicans entered the U.S. under the Bracero agreement during the war (Vargas 2017: 263). Unfortunately, despite the Mexican government’s efforts to secure a contract that protected the interests of Mexican workers, powerful farmer’s associations found ways to abuse the program. American “farmers continued to hire undocumented workers from Mexico,” which allowed them to circumvent provisions of the bracero agreement to the detriment of the undocumented. Moreover, “the bracero agreement [itself] undermined the wages of domestic farm workers, who were replaced by contract laborers from Mexico.” As Vargas has noted, “The flood of contract laborers and undocumented workers would contribute to canceling almost all of the accomplishments of Mexican Americans on the labor and civil rights fronts” (Vargas 2017: 263).

..

The More Things Changed, the More They Stayed the Same

The end of World War II ignited an unprecedented economic boom as U.S. industries turned from military production to the production of domestic consumer goods. Soldiers returning from the war easily found work—if they were White—whereas Mexican Americans and other racialized minorities often found the doors of opportunity closed as a result of the usual discriminatory social and economic practices that had always characterized life in the U.S.

Mexican Americans were also disadvantaged by the continuation of the Bracero Program, which was supposed to have been a temporary wartime program. The original rationale for the program had been to replace Mexican American farm workers who had been drafted or had volunteered in the armed services. However, big corporate growers, who were addicted to cheap labor, lobbied for the program’s continuance after the war. Many braceros simply remained as undocumented immigrants when their contracts expired, with the result that growers retained a ready pool of laborers, whose illegal status made them more susceptible to manipulation and who were willing to work for lower pay than returning Mexican American farm workers could have demanded (De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 136; 138).

The continuation of the Bracero Program also inadvertently encouraged illegal immigration by raising the hopes of new braceros so that many more applied than could be accepted. Applicants who were rejected often immigrated illegally. Moreover, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) frequently colluded with growers, opening the border whenever growers clamored for workers. The INS even sometimes helped farmers recruit workers from among the undocumented entrants, who were allowed to become legalized as they worked. At the same time, by failing to recruit native-born farm laborers, and hiring braceros instead, growers were routinely violating the original Bracero agreement (De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 136–139).

By 1959, braceros were even working at non-agricultural jobs, such as “lumbering, trucking, light manufacturing, and ranching.” Employers felt no pressure to provide decent working conditions, and the “bracero wage” was becoming the norm for all agricultural workers, including native workers. And in direct violation of federal regulations, growers sometimes even used braceros to break strikes.

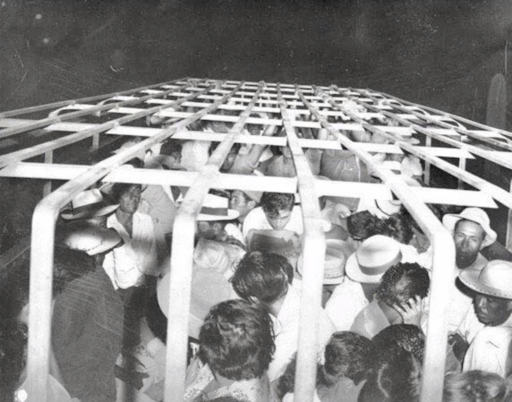

In 1954, in the face of an economic recession in which unemployment had doubled, the government finally responded in a heavy-handed way reminiscent of the mass deportations of the 1930s. In a highly publicized action known as Operation Wetback, federal agents sought to round up and deport undocumented Mexican nationals. Making few attempts to distinguish between American citizens of Mexican descent and undocumented Mexican nationals and with no recourse to due process, “this indiscriminate roundup caused families to be separated and children left behind” (Vargas 2017: 286–287).

Chicano Awakening

The 1960s and ’70s was a period of profound cultural, political, and social change in the United States. Many historically marginalized groups—Indigenous, Mexican, Black, and Asian—all mounted aggressive and sustained challenges to the systemic inequalities and institutionalized racism that had long plagued the nation.

Mexican Americans who came of age in the post-World War II years observed the growing prosperity of majority White communities and felt increasingly frustrated and disillusioned. Too often, their own communities continued to experience only persistent poverty, limited access to quality education, inadequate healthcare, and a lack of economic opportunities. Many of the most politically engaged Mexican Americans began to question whether the goal of trying to assimilate into mainstream society was a realistic one. Their elders had often assumed that assimilation was the best path to full and equal citizenship, but they had only been left further behind. Out of disillusionment, a new identity began to take shape—a Chicano identity—which in turn laid a foundation for the rise of a robust Chicano Movement, often referred to by participants at the time simply as el Movimiento.

But what is a Chicano? According to interpreters of the Chicano experience such as Maceo Motoya and Moctesuma Esparza, the word itself points to the Indigenous roots of Mexican people. It is a reminder of the clash between Spain and the Aztec empire in the 16th century. According to this understanding, the word Chicano was derived from the root word for Mexico which is based on the name of the Aztec Indians, who called themselves Meshica, not Aztec, as the Spanish called them. However, the Indigenous “sh” sound was written in 16th century Spanish as “x”—hence Mexica. According to Esparza, Chicano was simply a permutation of Meshica with the weak first syllable “me” dropped, leaving “shica” or “chica,” and that became Chicano—short for (Me)Chicano (Montoya 2016; Belton & Fritz 2013).

This Chicano awakening represented a profound generational shift involving a radical change in the way members of the Chicano Generation would come to define themselves, as contrasted with the way their elders in the preceding Mexican American Generation had defined themselves. Chicano historian Mario García’s description of this contrast is worth quoting at length:

The Chicano Movement in its revisionist and oppositional interpretation of history stressed that Chicanos were fighting not only class oppression and ethnic and cultural discrimination, but also deep-seated racism. Earlier Mexican American civil rights struggles from the 1930s to the 1960s led by the Mexican American Generation used a “whiteness” strategy to argue that if people of Mexican descent were being recorded in the U.S. Census as “whites,” then there was no basis for discrimination and segregation of Mexicans based on race. The Chicano Generation eschewed such a strategy and noted that Mexicans had always been racialized in jobs, wages, housing, and education. The very term Mexican was racialized so that anything Mexican was considered by whites to be inferior. Chicanos emphasized this reality. They also argued that since they were a people of color, they not only needed to be proud of this but to combat racism as a people of color. The concept of racialization was an important recognition by the Chicano Movement and a way of challenging the mythic “melting pot.” If there were such a pot, why had Mexicans and Black people, for example, not been melted? It was because of racialization, the movement argued (García 2021: 10).

While not discounting the heroic efforts of earlier generations of Mexican Americans—at labor organizing, challenging systemic discrimination, and fighting for educational rights—the new Chicanos faced the reality that these efforts had often failed or been only marginally successful. The Chicano Movement of the ’60s and ’70s would build on past legacies with renewed vigor and make unprecedented gains.

Huelga!: Organizing Farm Workers

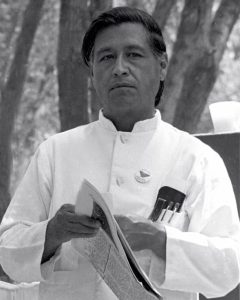

One of the most iconic achievements of the Chicano Movement was the successful effort to unionize farmworkers. In particular, the grape strike of 1965 centered in the San Joaquin Valley of California is often seen as the start of the Chicano Movement. The architects of this project were César Chávez and Dolores Huerta.

César Chávez was the first Chicano Movement leader to gain nationwide attention and is generally regarded as the Mexican American counterpart to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Moreover, Chávez was inspired by King’s philosophy of nonviolence as the best means of effecting change. Chávez understood from personal experience the hardships and suffering of migrant farmworkers. Indeed, his own parents had lost their farm during the Great Depression, forcing the family to become migrant farmworkers in order to survive. They had followed the harvest to California, lived in labor camps that lacked adequate sanitation, and César had even found it necessary to drop out of school in 8th grade to work full-time in the fields (Montoya 2016).

Dolores Huerta, who in cooperation with César Chávez co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (known today as the United Farm Workers), was initially less well known to the general public than Chávez, but she has become better known in more recent years. As of this writing, Huerta is 93 and still active in the labor movement. In the 1960s, Huerta was as dynamic and effective a union lobbyist, spokesperson, and negotiator as anyone in the labor movement. Known by her adversaries in agribusiness as “the dragon lady,” she often went head to head with the lawyers of the powerful growers and extracted agreements that even Chávez himself might not have been able to get. Although Huerta didn’t grow up working in the fields, her father had been “a farmworker, miner, and union activist who also served in the New Mexico legislature.” Huerta had studied to become a teacher before she veered off of that course to become a union organizer (Montoya 2016).

…

The beginning of the struggle against California’s most powerful growers came in September of 1965 when a rival union, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) led by Filipino American activist Larry Itliong organized a series of walkout strikes among Filipino grape pickers. Itliong asked Chávez to join the strike, and an ambivalent Chávez, unsure whether the NFWA was financially secure enough to mount a big strike but hesitant about keeping his own people on the job in the face of the Filipino walkouts, put the issue to a vote. The NFWA, which by then had grown to 1,200 members, voted to join the Filipinos in solidarity and strike against Schenley Industries and DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation, two of California’s largest growers. The striking workers were met with the usual tactics of violence and intimidation on the part of the growers (Montoya 2016).

…

In the end, the fight to improve the lives of farmworkers was a long and bitter one with small victories and numerous setbacks along the way. The fight over grapes alone, which began in 1965, was not resolved until 1970 when “Lionel Steinberg, the owner of Freedman Farms, signed a contract with the farmworkers union and a union label was placed on his table grape crates.” Grapes with the union label commanded higher prices, and “[i]t wasn’t long before other grape growers, tired of their fruit rotting in warehouses, signed similar contracts and received the now coveted union label.” When Giumarra finally came to the negotiating table and brought all the other table grape companies along, “Dolores Huerta negotiated a settlement … that provided higher wages and benefits for scores of workers, ending the most successful consumer boycott in labor history (Montoya 2016).

In 1972, the overarching union became known as the United Farm Workers of America, and the wages and working conditions for farmworkers continued to improve. Between 1970 and 1974, workers saw a 70% wage increase, and the introduction of health care benefits, disability insurance, pension plans, grievance procedures, the elimination of the backbreaking short hoe, the banning of many pesticides, and the introduction of unemployment benefits (Vargas 2017: 313).

* * *

Chicano Student Movement

Leaders like Chávez and Huerta inspired a whole generation of young urban Mexican Americans. Beset by feelings of alienation in their schooling and frustrated by chronically high levels of educational failure and the failure of schools to meet their educational needs, Mexican American students in the mid-1960s awakened to a new Chicano identity. In the decade of the ’60s, high school dropout rates for Mexican Americans were among the highest of any group in the U.S. The median grade attainment was only 8.1, compared to 9.7 for other non-Whites and 12.0 for Anglos. A major factor holding young Mexican Americans back was low expectations and pure neglect on the part of the largely Anglo teaching force in places like East Los Angeles and other urban school districts with large Mexican American populations (De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 164). In response, young Chicanos began to create advocacy groups on college campuses and in high schools, first in the Southwest and eventually across the country.

…

Student Movement in Higher Education

In the 1960s, more Mexican Americans than ever before were attending colleges and universities thanks in part to federal programs such as the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP), which actively recruited Mexican Americans, and the GI Bill, which assisted veterans. Inspired by el Movimiento and the larger civil rights movement generally, Mexican American college students nationwide became politically engaged and created student organizations on campus dedicated to making institutions of higher learning responsive to minority students. In the spring of ’68, shortly after the East Los Angeles student walkouts, Chicano students at San José State College expressed their disapproval of the status quo in California institutions of higher education by staging a walkout during the graduation ceremony (Montoya 2016).

As the fall of ’68 rolled around, Chicanos joined a coalition of student groups organizing as the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) and representing diverse ethnic minorities on campus including Blacks, Chicanos, Chinese and other Asians, Native Americans, and Filipinos. The TWLF staged a nearly five-month-long strike, from November 6, 1968 until March 21, 1969, at San Francisco State and the University of California at Berkeley to protest the perennially Eurocentric fixation of institutions of higher education in the U.S. and to demand a more balanced mix of ethnic studies programs, the hiring of more minority faculty, and the admission of more ethnic minority students at colleges and universities. The protests led to violent clashes between students and police, but in the end, the strikes led to the creation of the first Ethnic Studies Department in the country, at UC Berkeley (Montoya 2016).

* * *

During the 1970s, thanks to the Chicano Student Movement, more Latines would be attending colleges and universities than ever before “and they would eventually establish Chicano and Latino studies departments at over 160 universities” (Belton & Fritz 2013).

Mexican Americans and the New Immigration

Despite its many achievements, by the end of the 1970s the Chicano Movement had just about run its course. In 1983, the Los Angeles Times ran an article reporting that while a plurality of Mexican Americans identified as Latino, only a small minority (about 4%) were willing to embrace the term Chicano (De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 182). Of course, self-identified Chicanos had probably never been more than a small minority of the Mexican American population, representing only the most politically engaged. Nevertheless, like all the other ethnic civil rights movements, the momentum of the Chicano Movement eventually stalled.

Meanwhile, a new wave of immigration was under way, and a significant shift in immigration patterns was reshaping the demographic landscape of the United States. For the first time, the total number of immigrants from various Asian countries, including the Philippines, Vietnam, and Korea, was nearly as great as the number of immigrants coming from South and Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean. Between 1975 and 1989, for example, roughly 3.6 million immigrants arrived from various Asian countries. However, immigration from Latin America was also substantial—3.2 million from South and Central America and 1 million from Mexico (not accounting, however, for significant numbers of undocumented immigrants) [De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 183–184).

The late 1970s and early 1980s were economically turbulent times, and predictably, a substantial segment of the beleaguered American middle class perceived immigrants as threats to their economic well-being, a fear often exaggerated by sensationalist media coverage and political rhetoric, which framed immigrants as taking jobs away from American citizens.

Even the established Mexican American population, many of whom were second or third generation and native-born, were often ambivalent about the rising immigration trends. However, most Latines, whether poor or affluent, did not really regard competition for jobs as a serious threat to their livelihoods. They were more likely to feel that immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants, generally took on low-paying agricultural and service industry jobs (washing cars, and cleaning homes, hotel rooms, and offices, tilling gardens, and caring for the elderly parents of White folks) work that native-born Americans were increasingly unwilling to do. Nor did they think the new immigration from Latin America would negatively impact their lives in any other significant ways. Still, Mexican Americans who were more affluent and more highly educated did show a greater tendency to believe that the undocumented benefited unfairly from social services, such as public education. Moreover, those Latines who were most assimilated also tended to support stricter immigration controls (De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 184).

…

Heading into the dawn of the 21st century, the Mexican diaspora in the United States was more diverse than it had ever been. On the one hand, there were the fully assimilated, fourth, fifth, or sixth generation Mexican Americans living in metropolitan cities across the Midwest, Colorado, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California, who were often indistinguishable in their family structures and values from Anglo American families. On the other hand, there were the most recent immigrants, often rural folk with conservative, family-centric values, bravely navigating the challenges of adaptation and integration while striving for economic stability and community acceptance, often in hostile social environments (De León & Griswold del Castillo 2006: 187).

- This chapter is adapted from Who Are We? by Nolan Weil, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ↵

- The settlement of San Juan was preceded, of course, by a number of settlements on Hispaniola (present day Dominican Republic) and Cuba, but they don’t figure into this story because they aren’t U.S. territories. ↵