27 Indigenous America: Repression and Resurgence

First Nations

The Italian explorer, Christopher Columbus, is often credited as the person who “discovered” the Americas.[1] In 1492, Columbus broke with European sea-going tradition and sailed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean under the theory that the earth was round and that he could therefore reach the Far East by sailing west. When he ran into the island that became known as Hispaniola (shared today by the Dominican Republic and Haiti), he thought he had landed somewhere in the East Indies—the islands in or near the Indian Ocean. That being the case, Columbus referred to the people he encountered as Indians. Although based on a geographical error, the term stuck and is still used today to refer to the Indigenous people of the Americas as a whole.

Of course, many critics of the claim that Columbus discovered America will point out that the Norse explorer, Leif Erikson, actually beat Columbus by about 500 years. Sometime around the year 1,000, historians believe, Erikson founded the short-lived colony of Vinland in present-day Newfoundland, Canada. However, this Norse colony did not survive.

At any rate, from the perspective of America’s Indigenous peoples, both of these claims are Eurocentric distortions of world history. For by the time European explorers and settlers became aware of the Americas, both North and South America had already been discovered, explored, and settled for over 12,000 years (and perhaps for as long as 20,000 to 30,000 years) (Raff 2020).

Well before the establishment of the United States, there were perhaps five to ten million Indigenous people organized in over six hundred independent tribes, bands, and groups inhabiting every part of North America. Each group had its own land base, language, economic system, government, social institutions, and cultural distinctiveness. Some groups lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering; others practiced intensive horticulture and trading. Some societies were organized in simple bands while others had complicated confederated governments. Hundreds of different languages were spoken representing as many as twelve distinct and unrelated linguistic families. Contrary to the way some early colonial sources portrayed North America, it was NOT an uninhabited wilderness (Wilkins and Stark 2011).

“Patterns: Examining American Indian Imagery in La Crosse”

It’s important to recognize that the descendants of the first inhabitants of the Americas are still here today, including in the lands currently known as the United States. But unfortunately, continued Native presence is too often overlooked in discussions of the character of contemporary America. Here in the United States today, Native Americans are sometimes imagined as people who lived in the past, dressed themselves in picturesque clothing, and gave European settlers a hard time before finally being subdued in the final few years of the 19th century. Too many non-Indigenous people forget that like every other population, Native people moved forward with the times, even as they had to endure more than their fair share of hardship and sorrow throughout the 20th century and now on into the 21st.

This brief video by former UWL students focuses on Native American issues within Ho-Chunk Nation land, or the La Crosse area, and includes several moving testimonies from Native faculty and students at UWL.

After watching the video, share your thoughts on the following questions:

- What are some of the ways that “Indian” mascots are harmful to the Native community? Please use specific examples from the video.

- Were you surprised to learn about UWL’s former mascot? How do you think you would have voted?

Speaking of Indians

The National Museum of the American Indian has noted that American Indian, Indian, Native American, and Indigenous American are all acceptable when discussing Indigenous Americans in general. However, not every Indigenous person will find every one of the above terms acceptable. Indeed, it might be the case that older generations of Native people are okay with the term “Indians” as a collective reference, while some among the younger generation are not.

It is also important to note that there is no such thing as a single, unitary group that comprises the Native American community. On the contrary, the Native population consists of hundreds of distinct tribes, which are historically and legally related to the United States as sovereign nations. This fact is significant for the question of how Indigenous communities self-identify. To be competent cross-cultural communicators, non-Indigenous people need to understand that “indigenous communities expect to be referred to by their own names—Navajo or Diné, Ojibwe or Anishinaabe, Sioux or Lakota, Suquamish, or Tohono O’odham” (Wilkins and Stark 2011).

The above examples may leave some readers wondering why so many tribes seem to have multiple names. The reason is that when Europeans first encountered Native peoples, they named them in Spanish, or French, or English, and the tribes became known by those names. For example, Navajo comes from Spanish, while the “Navajo” people call themselves Diné in their own language; Sioux comes from French, while some “Sioux” people refer to themselves as Lakota or Dakota. (It is actually somewhat more complicated than this, but the current explanation should be sufficient for our present purposes.)

It may all seem hopelessly confusing to non-Native people, but the key takeaway is this: in interacting with particular Native people, or “when talking about Native groups or people, use the terminology the members of the community use to describe themselves collectively (National Museum of the American Indian 2025). When in doubt, be a good listener, and if that isn’t enough, one can ask: “how do the people of your community prefer to be identified by outsiders?” Or “what tribal name do members of your community consider proper and respectful?”

Nations, Not Minorities

Literally speaking, a minority group is a group of people who are present in fewer numbers than the members of some larger group. However, in social, political and legal discourse, “a minority group [also] refers to a category of people who experience relative disadvantage as compared to members of a dominant social group” whether or not the minority group is smaller or larger than the dominant group in terms of population numbers.

In the United States, minoritized[2] groups would include African Americans, Asian Americans, Latine Americans, women, queer and gender non-conforming people, to give just a few examples. Notice that Native Americans are missing from this list of examples. By the definition quoted above, one might think that Native Americans surely fit the definition of a minoritized group, and indeed they do. Native Americans are both a numerical minority and a category of people who generally do not share the same power, privileges, rights, and opportunities as the white, Anglo majority. On the other hand, because of the unique status of Native American tribes as sovereign nations vis-à-vis the United States, Indigenous peoples are not minorities in the same way that other racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. are (Wilkins and Stark 2011). Because each and every Native American tribe is a sovereign nation, Native Americans should not be categorized as an ethno-cultural minority group (Schulte-Tenckhoff 2012).

To appreciate this point, it is important to remember what has already been said about the state of affairs in North America when Europeans began colonizing it—i.e., there were over six hundred independent tribes, bands, and groups of Indigenous people already here. Some of the larger nations coexisted with other nations by means of sophisticated inter-national alliances. Some nations were economically and militarily powerful. Nations sometimes waged war against one another, but they also negotiated and maintained peace through the exercise of careful diplomacy.

After American independence, the United States entered this historical moment as just another nation among nations. At the time of the founding and for many years after, American leaders understood that as a practical matter no sovereign nation could bind another sovereign nation to its own laws and its will without great cost. Powerful though the United States was becoming as its population grew in the late 17th and 18th centuries, the power of Indigenous nations was not insignificant. Just as it was necessary to mediate disputes with sovereign nations like England, France, and Spain by negotiating treaties, the U.S. had to deal with the Native tribes as the sovereign nations they were, by negotiating treaties.

A treaty is “a formal agreement … between two or more sovereign nations that create[s] legal rights and duties for the contracting parties” (Wilkins and Stark 2011). Thus, from the beginning, the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the United States “was a political one, steeped in diplomacy and treaties” (Wilkins and Stark 2011). No other racial or ethnic minority in the United States has or can have this kind of relationship with the federal government; for this reason, Indigenous legal scholars and activists continually emphasize the point that Native American peoples are not minority groups.

Resisting Settler Colonialism

No one with a sense of social justice can study the history of Indigenous America without feeling anger, outrage, righteous indignation, and sadness. Most non-Indians are never exposed to a full recounting of the injustices that Indigenous peoples have endured as a result of U.S. settler colonialism.[3] Usually, these injustices are merely hinted at as if they were simply the unfortunate errors of a less enlightened past, best forgotten and largely overcome today. But the past is rarely ever past, and the descendants of Indigenous peoples continue to live with the consequences of the U.S. settler colonial regime established even before the nation’s founding and then maintained ever since. This chapter provides a brief outline of that history, focusing on “boarding schools,” the Red Power movement of the 1960s and ’70s, and the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement of today.

“Manifest Destiny”

Europeans believed their takeover of the Americas was their God-given right, or Christian duty. They saw themselves as bringing “progress” and “civilization” to “backwards” and “primitive” Natives, particularly as the colonies expanded westward, as famously depicted in the 1872 painting entitled “American Progress,” by John Gast. Manifest Destiny positioned the original inhabitants of the continent as a problem, as they were impediments to this religious calling (and economic imperative). The nascent U.S. government’s three proposed “solutions” to the so-called Indian problem were: 1. geographic removal, typically onto reservations, 2. military subjugation, also known as genocide, and 3. forced assimilation via the now-notorious “boarding schools” (called “residential schools” in Canada), which some Indigenous people also refer to as genocide, given the boarding schools’ attempted wholesale destruction of Indigenous cultures.

Geographic Removal and Military Subjugation

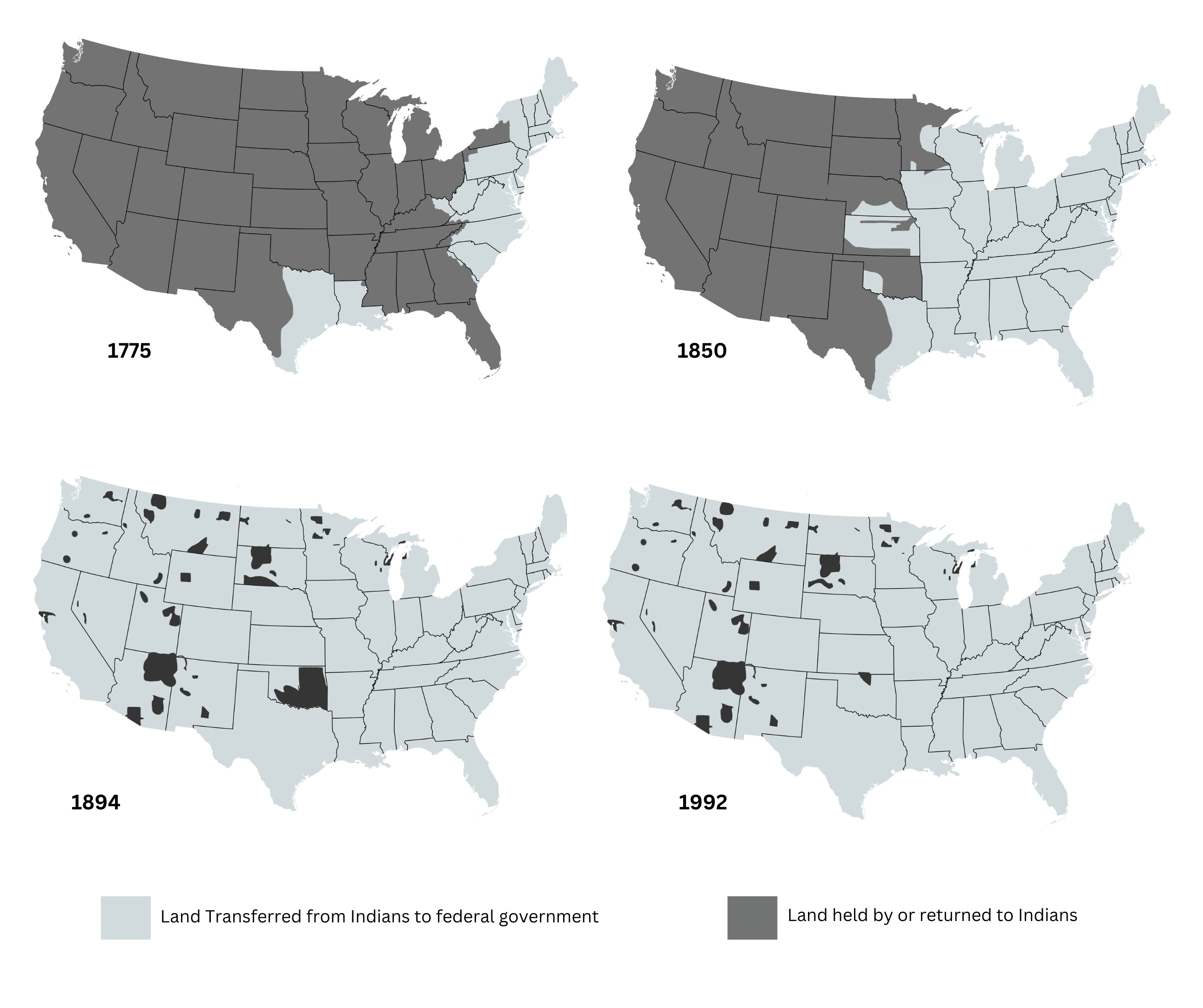

Historically, the United States pretended to deal with Indians in ways that had an appearance of legality, for instance by negotiating treaties and buying lands from various Indian tribes, but such treaties were often negotiated when Indian peoples were under duress and had little choice but to agree to bad deals. (See, for example, what happened to the Dakotas in 1862; Lee and Ahtone 2020). In some cases, they were virtually forced to sign treaties or face violent reprisals. The map below is a dramatic illustration of the results. The areas in white represent the lands transferred from Indians to the federal government between 1775 and 1992. The areas in dark represent lands held by Indians or returned to them. Today, tribal lands in the continental United States (including Alaska) only constitute 100 million acres, or 4% of the land (Wilkins and Stark 2011). This is roughly the size of the state of California.

Removal involved the large-scale migration of Indigenous people from lands that they previously occupied, often after they had already made concessions to accommodate colonial populations and had moved from ancestral lands to settle in new places. The story of Indigenous removal is a long one. Numerous Native communities in every part of the continent from the Atlantic coast to California faced it throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Sometimes Native communities moved voluntarily, even if reluctantly, just to get away from troublesome whites. But history is also replete with stories of forced removal, the most widely known of which was a series of forced relocations between 1830 and 1850 of 60,000 Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw from the Southeast to areas west of the Mississippi River. The forced relocations carried out by the government after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 resulted in the death of thousands of Native people and is known as the Trail of Tears.

By 1850, the United States had expanded westward to the Mississippi River, and the eastern half of the country was firmly under settler-colonial control. The West had been designated as Indian Country by this time, and many Eastern Native nations had been relocated there, yet white settlers were now coming for the lands west of the Mississippi.

The various Indigenous nations of the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, and Desert Southwest did not submit easily to such settler colonial domination. After 1865, soldiers, battle-hardened in the American Civil War and armed with advanced weaponry, now came west to subdue the “hostile tribes.” But Native fighters were formidable, and the U.S. Army in the West lost many battles. The most famous military defeat is surely the annihilation of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

The U.S. Army often responded to their humiliating defeats by launching attacks on Native villages and indiscriminately killing women, children, and elders. The so-called “Indian Wars” lasted for more than fifty years. The “Sioux Wars” and the “Apache Wars” are perhaps the most dramatic examples of the long-running resistance of Western Indian nations to U.S. domination. Some conflicts in the Southwest persisted even into the early 20th century, but for the most part, the dispossession of Indian lands was complete by about 1890. In the end, Indigenous people were unable to withstand the sheer force of numbers and overwhelming abundance of military resources that the United States was able to throw at them.

Boarding Schools and Cultural Genocide

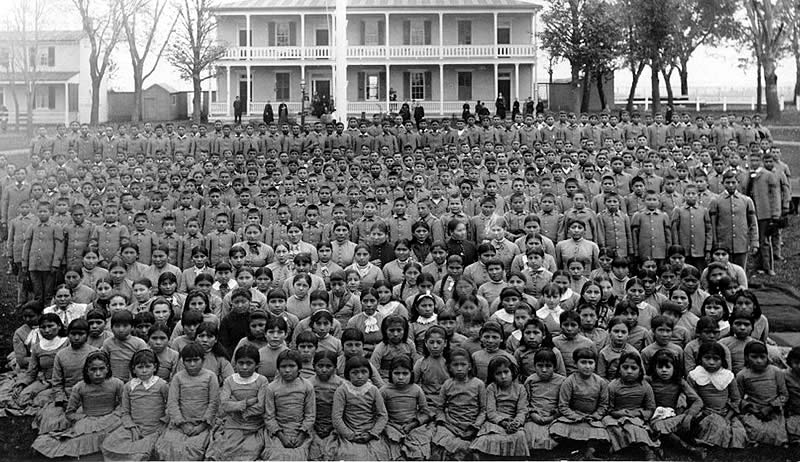

Another violent attempt to erase Native culture involved the establishment of boarding schools. The first boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was established in Pennsylvania in 1879 by Richard Henry Pratt, a Civil War veteran and a veteran of the Indian Wars. In 1875, Pratt had been given the task of interviewing Indian combatants after their capture to determine how they should be charged. “Somehow his sympathies were engaged, and he tried to clear as many of them as possible.” But since the combatants were deemed too dangerous to return to their tribes and homelands, Pratt was then tasked with escorting them to prison at Fort Marion, Florida where Pratt began experimenting with Indian education, hiring teachers to instruct them in English, art, and mechanical studies. Impressed by “the Indians’ aptitude for ‘civilization,'” as Pratt put it, he would eventually lobby Congress for funds to set up a school dedicated to “the civilization of American Indians” (Truer 2019).

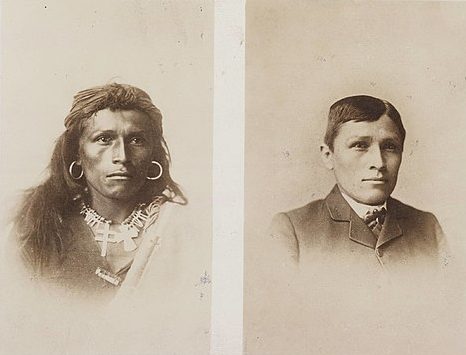

Pratt was open-minded, even radical for his time, believing that all human beings, given equal opportunities, would have equal capacities. Nevertheless, he was still caught up in the white supremacist ideology that could see no redeeming value in Native culture. Reflecting on his mission, Pratt once opined:

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one … In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man (Truer 2019: 133).

After the establishment of Carlisle, dozens of other boarding schools sprang up across the country. Some parents, believing that assimilation was inevitable, saw the boarding schools as opportunities to enable their children to adapt successfully to the realities of life in a world dominated by whites, and they sent their children willingly. But too often parents were coerced against their better judgement into participating in the boarding school system.

Although not every Indigenous person who attended a boarding school has condemned the experience, the system is notorious for its cruelty and abuse.[4] From the moment children arrived at boarding school, they were systematically robbed of their cultural identities from the hair on their heads to the clothes they wore and even the languages they spoke and the religions they practiced. For instance, children were prohibited from speaking their native languages and a typical punishment for anyone caught doing so was to have their mouth washed out with soap. Beatings, confinement with only bread and water for rations, denial of comfort and medical care when ill, and sexual abuse were not uncommon (Treuer 2019: 137–139). Generations of Native children were thus brutalized and traumatized, leaving them cut off from their families and their heritage and stripped of self-esteem, angry and often broken for life.

But none of what has been said above should be taken to mean that Native peoples accepted their circumstances passively. From the origins of settler-colonialism on, tribal nations and individuals engaged in resistance and negotiation with the policies that were imposed upon them.

Dark La Crosse Stories #63: St. Mary’s Boarding School in Wisconsin

In 1883, the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration [FSPA] in La Crosse opened the St. Mary’s Indian School, a boarding school that was on the reservation of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Chippewa Indians with the mission to convert Ojibwe children to Catholicism, a history the FSPA now must reconcile with the survivors and descendants of St. Mary’s.

Watch/listen to the podcast below, then answer the following questions.

- Why does Tracy Littlejohn describe the boarding schools as an act of genocide?

- What are the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration doing today, to help heal and repair the harms of their mission in the not-so-distant past?

The Rise of Red Power

During the 1960s and 1970s, U.S. government policies towards Native people still left much to be desired, but they helped put Native tribes on the road to self-determination. However federal government policies alone were not responsible for the strides that Native peoples would make in the second half of the 20th century. As David Treuer points out, “change was coming from within Indian communities, too” (2019: 290). Indeed, many of the changes in government policy were the result of Native activism.

While Native Americans created many different organizations in pursuit of their interests throughout the 20th century, three organizations that emerged in the middle decades of the century are particularly significant for understanding the reawakening of Native pride and the collective determination on the part of Native Americans to reclaim their heritage and culture.

These three organizations—the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), and the American Indian Movement (AIM)—all shared the same objectives although they differed radically in tactics. Moreover, their vision of what Native peoples could and should be was markedly different from that of the prominent Indian leaders born a generation or more earlier. Rejecting the old so-called “progressive era” ideologies of assimilation and acculturation, the new Indians advocated instead: cultural preservation, enforcement of treaty rights, self-determination, and tribal sovereignty.

Perhaps the most widely-remembered event of the early Red Power era was the 1973 AIM takeover of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Near the southwest corner of what is now South Dakota, Wounded Knee had been the site of a massacre in 1890 of at least 250 men, women, and children by the U.S. Seventh Cavalry and is typically regarded as marking the end of the Sioux Wars. The symbolic significance of Wounded Knee for Lakota people undoubtedly played a role in AIM’s decision to occupy it as a way of calling attention to the U.S. legacy of injustice towards Native people.

The siege of Wounded Knee got a lot of media attention until it became too dangerous for reporters to stay. The public was shocked to witness, in 1973, Native fighters, armed mainly with shotguns and hunting rifles, facing armored personnel carriers, helicopters, and federal troops armed with automatic weapons. The image was not a good one for the United States, especially considering the history of Wounded Knee, and many non-Indigenous Americans were sympathetic to AIM. Towards the end of the standoff, several modest agreements were reached: “the Oglalas would have their grievances heard by the Whitehouse, and the Justice Department would investigate criminal activity on Pine Ridge,” but AIM leader and spokesman “Russell Means would turn himself in and face the charges against him” (Treuer 2019: 322–325).

It is difficult to assess the legacy of AIM. We may think AIM’s tactics were extreme, but in effect, they revealed the extremes to which the U.S. has gone (and continues to go) to maintain the racial, ethnic, and economic status quo.

Native Women and Red Power

Often overlooked in telling the story of AIM, and indeed in the telling of many civil rights and liberation stories, is the role of women. In fact, after the Wounded Knee occupation, it was Native women who made many of the most constructive contributions to the Red Power movement. There is perhaps no more iconic example than Madonna Thunder Hawk. Present at Alcatraz and Wounded Knee, Thunder Hawk’s most important work came after the Wounded Knee occupation.

Thunder Hawk has continued right into the twenty-first century her tireless leadership and advocacy for Native peoples’ rights. For instance, she played a role in the establishment of the Lakota People’s Law Project, and she continues to fight against resistance from the state of South Dakota for the rights of Indigenous children to remain under Native kinship care in legal accordance with the Indian Child Welfare Act. In 2016, Thunder Hawk joined the movement against the Dakota Access Pipeline, camping at a protest on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota. And more recently, she had a hand in the founding of the Women Warrior’s Project and participated in the documentary, Warrior Women, which highlights the contributions of Native women in the fight for social justice in Indigenous communities.

“Bring Her Home” and the MMIW movement

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement works to put an end to the horrific fact that Native women are murdered at a rate ten times higher than the rest of the population, and that murder is the third leading cause of death for Native women. The 2022 PBS documentary Bring Her Home, based in Minnesota and North Dakota, follows three different Indigenous women, an artist, and activist, and a legislator, on their unique yet interconnected journeys of seeking justice for their families and communities.

- This chapter was adapted from Who Are We? by Nolan Weil, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ↵

- As discussed in Unit 1, here we use "minoritized" rather than "minority" to emphasize the social and political emergence of these categories. ↵

- For further reading, see Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's book An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. ↵

- For testimonies from boarding school survivors and their descendants, watch the 2008 documentary Our Spirits Don't Speak English. ↵