30 Chinese America: Excluded Yet Essential

This chapter focuses on Chinese America but of course there are several more Asian American histories, such as Japanese America, Vietnamese America, and Hmong America, among many others. To learn a broader history of Asian America, we suggest taking RGS 350 Asian American Studies in Race, Gender, and Sexuality, or RGS/ANT 362 Hmong Americans, for example.

Prelude to a Chinese Diaspora

The first record of Chinese people arriving anywhere in the United States was 1785.[1] Three Chinese sailors working on a merchant ship, which docked in Baltimore, Maryland, were left behind when the ship departed again. The three men spent years petitioning the U.S. government to send them back to China. Chinese sailors were also present in small numbers in Hawai’i during the last decades of the 18th century when Hawai’i was still a sovereign island kingdom. But for the most part, before the 1850s, very few Chinese immigrants had come to the continental United States. “The first Chinese to immigrate to the United States (intentionally) came principally from the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong Province in southeastern China” (Yung et al. 2006: 1). Over 300,000 Chinese, the vast majority from Guangdong, entered the United States between 1852 and 1882.

Why Guangdong?

Guangdong province faces the South China Sea. From the ports of Canton, present-day Guangzhou, forty-two miles up the Pearl River, products such as silk, tea, and porcelain were shipped to international markets. Canton was also the only Chinese port open to foreign merchant ships, and contact with foreign merchants and explorers from every corner of the world, gave Canton a cosmopolitan and progressive character, one less firmly attached to only traditional Chinese values (Chang 2004).

While Beijing, the seat of government in the north of China, was preoccupied with the study of Chinese classical literature, which was the gateway to the civil service bureaucracy and to social status, Canton and the other port cities of southern China were more interested in business and commerce (Chang 2004) and a great deal of wealth flowed into China through its coastal cities—so much wealth that the standard of living in China throughout the 1700s was, on the average, equal to that enjoyed in western Europe. In fact, right up until 1800, China was probably still the richest country in the world, producing a larger share of the world’s total manufactured goods than all of Europe, including Russia, combined (Holcombe 2017).

However, by 1800, the Qing government’s military campaigns had not only been expensive, but they had left behind many religious and ethnic resentments. Imperial favoritism and widespread corruption angered people, and there was a large-scale anti-Qing movement that sometimes erupted in violent rebellion (Tong 2000).

In addition to these internal challenges, the Qing faced insurmountable external challenges. In particular, as the nineteenth century got under way, it became increasingly difficult to stand up to aggressive British imperialism. British merchants, disgruntled about their inability to find a product to market successfully in China, thought that they had finally found one in opium, an addictive narcotic that they sought to import from India. But they had a problem. The opium trade was illegal in China. Frustrated by the refusal of the Qing government to relax its restrictions on opium, British merchants smuggled it in illegally. The flow of opium into China quadrupled from 1780–1790 (Holcombe 2017).

Widespread opium addiction caused serious social and economic harm, and finally China cracked down on the illegal trade. A series of escalating tensions resulted in the so-called first Opium War (1839–1842) during which the British occupied Canton briefly and eventually won concessions from the Qing government that ran contrary to Chinese interests. As a result of the Treaty of Nanking that formally ended the Opium War, China was forced to open its ports, allow the importation of opium, and pay massive indemnities. To pay the indemnities, the Qing increased taxes on the peasants who were already “slaves to the land, living a hand-to-mouth existence, owing heavy rents and the cost of supplies to their landlords” (Chang 2004: 15). Unable to pay their debts, many peasants lost their land.

People who made their living in the handicrafts industry also took an economic hit as cheap, mass-produced, foreign goods flooded the market, reducing demand for traditional handmade products. (Tong 2000). And in 1847, British banks cut off funding to warehouses along the Pearl River, setting off a credit crisis that almost completely shut down trade for a year, throwing a hundred thousand laborers out of work (Chang 2004).

Faced with so much civil unrest, financial distress, economic dislocation, and hostile ecological conditions, some Chinese chose to leave their villages for distant lands in search of better lives.

East to Gold Mountain

In 1848, gold was discovered in California, and not long after, stories began to circulate in Guangdong about Gam Saan—“Gold Mountain”—a fabulous land of wealth far away across the sea.

It was not that the inhabitants of Guangdong were completely unaware of California before 1848. Yankee traders and missionaries had showed up regularly in the late 1700s. Moreover, direct trading links between Guangdong and California had existed since the early 1800s. A two-way traffic of valuable goods had developed—for example, sea otter skins from America and ornate furniture from China—and news from America regularly circulated in southern China. Some Guangdong residents even had friends and relatives who had gone to California before it became a popular destination. So California was already alive in the popular imagination.

As life became increasingly precarious in Guangdong, residents from all walks of life embraced the dream of striking it rich in California. “Hired hands, poor peasants, sharecroppers, and small landowners” were all looking for new ways to make a living. But not every would-be migrant was poor and desperate. Many in the upper classes, who had already migrated within China to adapt to social and economic dislocation, hoped to emigrate as a way of maintaining their previously acquired status and lifestyle. In other words, they sought to maintain control over their own lives, and they did so by capitalizing on a social network of friends and acquaintances (Tong 2000).

By 1849, 325 Chinese migrants joined the so-called “49ers” rushing to California from all across the United States and from elsewhere around the world to search for gold. The following year, 450 more Chinese came, and after that the numbers grew by leaps and bounds—”2,716 in 1851, and 20,026 in 1852. By 1870, there were 63,000 Chinese in the United States” (Takaki 2008: 179–180). By 1930, the number of Chinese that had crossed the Pacific was 400,000, about half of whom stayed and made the United States their permanent home.

The overwhelming majority of the earliest Chinese migrants were men. Half of them were married, and they thought of themselves as sojourners only—temporary visitors—who would stay just long enough to make an easy fortune in gold and return to their wives and families. Most came as free laborers and paid their own way out of their own savings or by borrowing from family or by securing a ticket on credit from an emigration broker, whom they would pay back later in installments, with interest. The transport ships were often overcrowded, foul smelling, and disease ridden, and many passengers must have regretted their decisions to undertake the Pacific crossing. Many died; their bodies were simply thrown overboard (Takaki 2008, Tong 2000, Chang 2004).

Those who survived generally disembarked in San Francisco. Before the gold rush, San Francisco was just a sleepy, sparsely settled area of sand dunes and hills with a population of only 500. Between 1848–1850, it exploded into a boom town of thirty thousand, rivaling Chicago, and by 1851, it numbered among the largest cities in the United States (Chang 2004).

Joining the Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush did not last very long. After news of a big discovery in the Sacramento Valley circulated in 1848, the first massive wave of fortune hunters came to California in 1849. From 1849 until 1852, the amount of gold that was discovered rose every year: “$10 million in 1849, $41 million … in 1850, $75 million in 1851, and $81 million in 1852.” After that, the amount discovered each year decreased until 1857, when it leveled off at about $45 million per year (PBS 2025). Like most other people arriving in San Francisco in those days hoping to become rich, the Chinese quickly left the city for the gold fields in California’s interior.

During the 1850s, about 85% of the Chinese who had come to the United States were panning for gold in the rivers of northern and eastern California. Prospecting for gold was hard work, but it also required good luck, and not everyone got lucky. But some people did. Chinese miners took millions of dollars worth of gold from the California gold fields. Some returned to China and invested their newfound wealth. Others stayed in the United States and lived off of theirs. So dreams of becoming rich came true for some gam saan haak (“travelers to Gold Mountain”). But many more found only hek fu (pain, adversity).

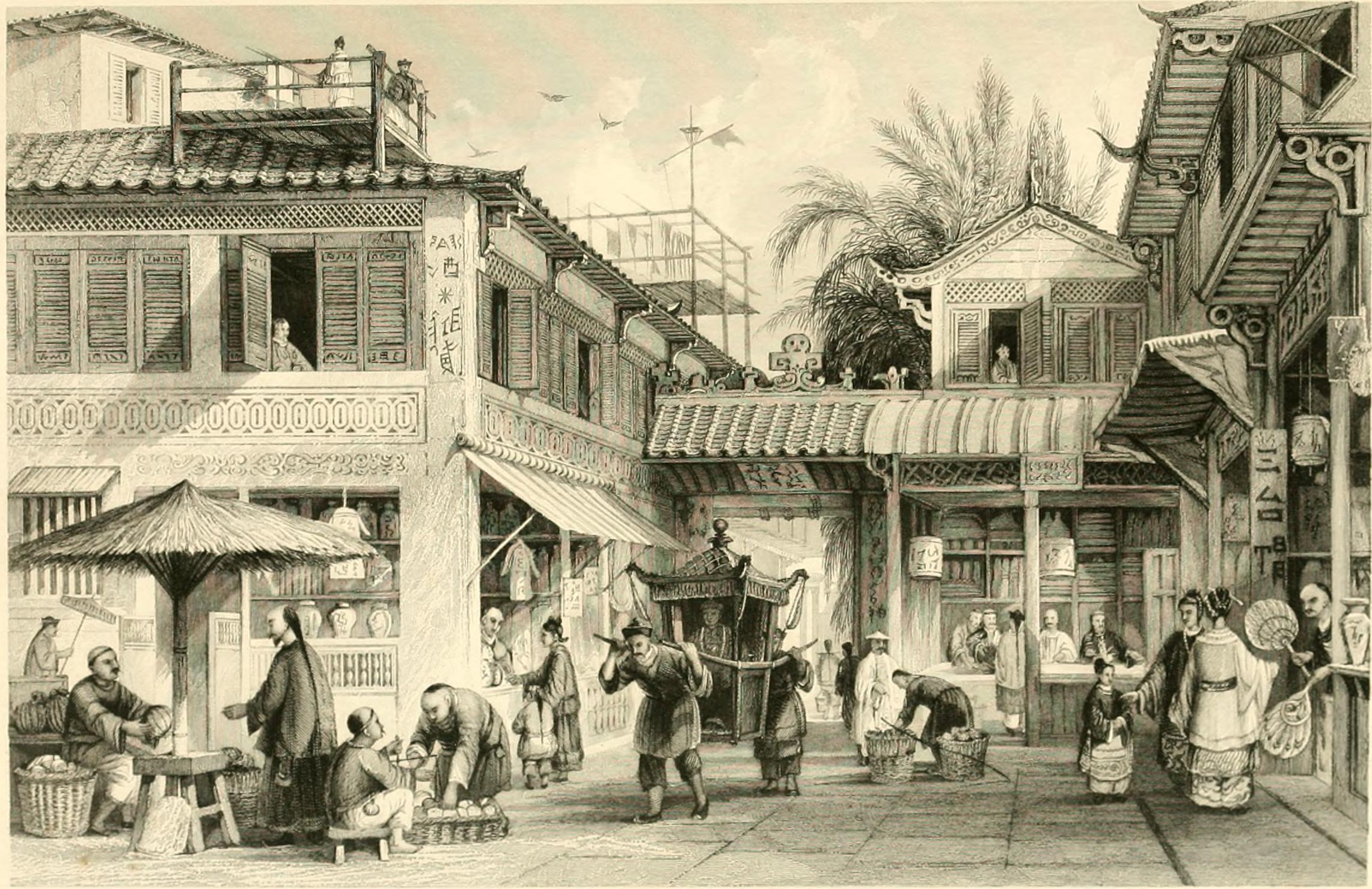

Although the vast majority of Chinese immediately headed out to the rural mining camps, a few remained in Dai Fou (the “Big City, i.e. San Francisco). Clustering together near Sacramento and Dupont Streets, they constructed rough shelters and built brick stoves and chimneys like the ones they had used back home. The community quickly expanded to take up about ten blocks. Known at the time as “little China,” “little Canton,” or “the Chinese quarter,” the area eventually evolved into San Francisco’s present-day Chinatown.

Anti-Chinese Backlash

When Chinese people first began arriving in California, it had seemed like they were welcome. But it did not take long before they encountered a nativist backlash. American miners were of the opinion that the gold in California should be reserved for Americans. The newly constituted state of California sided with the American miners by passing a series of taxes aimed at foreign miners. In 1852, for example, California passed a foreign miner’s tax that required a monthly payment of three dollars from every foreign miner who did not desire to become a U.S. citizen. The law was clearly designed to discriminate against the Chinese in particular, who could not become citizens by virtue of the Naturalization Act of 1790 that restricted citizenship to “free white persons.” Since Chinese people were not considered white, they were ineligible for citizenship even if they had desired it (Takaki 2008, Chang 2004).

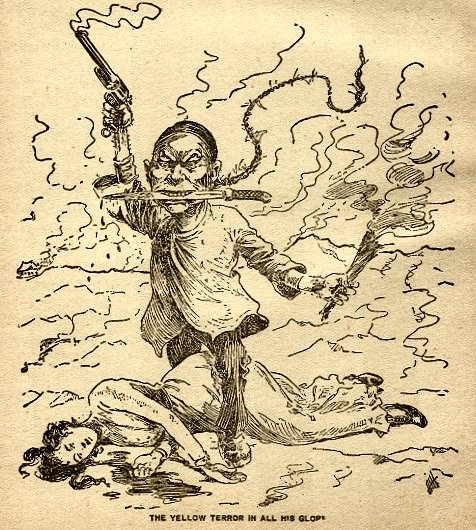

While Chinese people were not the only immigrant gold rushers, they stood out from other immigrants in their appearance and cultural norms and tended to be more easily singled out for abuse at the hands of nativists. The possibility of becoming a victim of mob violence was a constant threat. When not subject to outright violence, they often had to endure racist and xenophobic rants, not only from ordinary citizens, but also from government officials and political elites (Chang 2004).

After the Gold Rush

By the mid-1860s, when gold became more scarce and harder to find, many Chinese gave up mining. Some of them turned to fishing, where they could be found at work from Oregon to Baja California. They could also be found catching and processing shrimp from the San Francisco Bay (Tong 2000). But a great many Chinese found work on the transcontinental railroad. In 1862, the Central Pacific Railroad Corporation had secured the contract to lay tracks eastward from Sacramento through California’s rugged Sierras and across the deserts of Nevada and Utah to meet up with the Union Pacific, which was coming West across the Great Plains and through the Rocky Mountains (Chang 2004).

At first, Central Pacific contractors were reluctant to hire Chinese workers, but when the promise of high wages failed to attract white workers in sufficient numbers, the company began employing Chinese workers. Not only could the company hire Chinese workers at lower wages, but the Chinese proved themselves to be harder workers and more reliable—so much so that the Central Pacific advertised in Guangdong to bring more Chinese workers to the United States. In the peak years of construction, the Central Pacific employed some 10,000 Chinese men (Chang 2004).

The story of the building of the transcontinental railroad is one of toil and blood, heroism and tragedy. The task was unimaginably difficult and dangerous. The route involved drilling tunnels through mountains with nothing more than handheld drills, explosives, and picks and shovels. The rock in some places was so hard that by some accounts, the work proceeded, on average, only seven inches a day. Accidents, disease, and brutal weather were constants, especially in the steep Sierras. Before the railroad was completed, at least 1,000 Chinese workers had died; 20,000 pounds of bones were shipped back to China (Chang 2004).

The transcontinental railroad was eventually completed on May 10, 1869, when the railway crews from east and west finally met at Promontory, Utah. As Iris Chang has argued, it is doubtful the railroad would have been completed without the labor and know-how of Chinese railway workers. The railroad became the source of great wealth for American capitalists who oversaw its construction, yet all through the process, the Central Pacific contractors cheated the Chinese out of everything they could get away with, exploiting their vulnerability as migrants, paying them less than their white counterparts, and even trying to write the Chinese contribution out of history altogether by excluding them from the ceremonies that marked the great achievement. In photos from the era and other popular depictions of the driving of the final spike, Chinese workers are nowhere to be seen. And immediately after the completion of the railroad, “the Central Pacific … laid off nearly all of its Chinese workers, refusing to give them even their promised return passage to California. … [N]ow homeless as well as jobless, in a harsh and hostile environment,” many former Chinese railway workers “straggled by foot through the hinterlands of America, looking for work that would allow them to survive, a journey that would disperse them throughout the nation” (Chang 2004: 64).

The Great Dispersal

In the 1870s, Chinese workers migrated to every region of the United States in search of work. They sought out agricultural work in California’s Sacramento-San Joaquin valleys. They showed up in the salmon canneries that stretched from northern California to Alaska. They went to the Pacific Northwest to help build the Northern Pacific railway or to work in lumber mills. They were recruited for plantation and railroad building in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida. In Florida, they also worked on drainage operations, in construction, and in turpentine camps. They found their way to the Northeast to Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, where factory owners used them as strikebreakers in shoemaking and other industries. This antagonized the displaced workers, who were mostly Irish employees and already not very fond of the Chinese. In New York and Boston, they engaged in cigar making and cigar peddling, ran boardinghouses and laundries, and engaged in maritime shipping and retailing (Tong 2000).

As Chinese men dispersed across the country, many fathered mixed-race children. Marriages between Chinese men and Irish women were particularly common in 19th century America in places like New York. The experience of Irish women was in many respects similar to that of Chinese men in that many Irish women migrated alone, without families. Irish women sometimes outnumbered Irish male arrivals two to one. It was only natural that Chinese men and Irish women would compensate for the shortage of prospective marriage partners by intermarrying. For many Chinese men, intermarriage was often the tipping point in an assimilation process that got Chinese men starting to say “back in China,” rather than “back home (Chang 2004: 110–113).

While many Chinese men dispersed across the country, many others returned to San Francisco, which had become “a burgeoning city of opportunity.” Los Angeles, too, had a vibrant Chinatown, one that tripled in size between 1880–1890 (Tong 2000: 32–33).

The Conspicuous Absence of Women

More than any other immigrant group in 19th century America, the Chinese population was conspicuous in its absence of women. In 1860, for example, there were 33,149 men and only 1,784 women—a ratio of 186 to 1. And so the situation remained throughout the entire 19th century (Tong 2000).

A number of reasons have been offered to explain this disparity. First, traditional Chinese culture was extraordinarily patriarchal—rooted in a traditional Confucian ideology that relegated women exclusively to the domestic sphere of life, subordinated at every stage of life to a man. Women were to obey their fathers in childhood, their husbands in marriage, and their eldest sons in widowhood. Single women could not travel unaccompanied to distant places, and married women remained at home (Tong 2000). Moreover, when their husbands migrated to the United States, married women remained in China because it would have been too expensive for them to travel with their husbands and because husbands expected to be gone only temporarily, perhaps a year or two at most—just long enough to strike it rich and return with enough wealth to live a better life in China. In addition, the harsh frontier conditions in the U.S. made it a dangerous, unstable, and forbidding place—not a place suitable for a family. But even if married men had wanted to bring their wives, the reality was that “many whites viewed America as a ‘white man’s country’ and perceived the entry the entry of Chinese women and families as threatening to racial homogeneity.” The U.S. Congress even passed laws to prevent it (Takaki 2008).

Of course, Chinese women were not completely absent from Chinese communities in America in the 19th century, but compared to other immigrant communities, they were significantly underrepresented, as the statistics cited earlier clearly show. The same thing was true for children. While not absent, they made up a relatively small proportion of the Chinese population when compared with children from other immigrant groups. Merchants and consular officials were among the only classes that had both the necessary wealth and privilege to support families. Another unfortunate reality was the exploitation of some young women, especially poor young women, who were sometimes lured to immigrate under false pretenses. Transported to America in the belief that they were entering into marriages, they arrived only to discover that they had been sold into sex work. The lives of women who fell victim to such deceptions were often violently tragic (Takaki 2008).

Chinese Exclusion

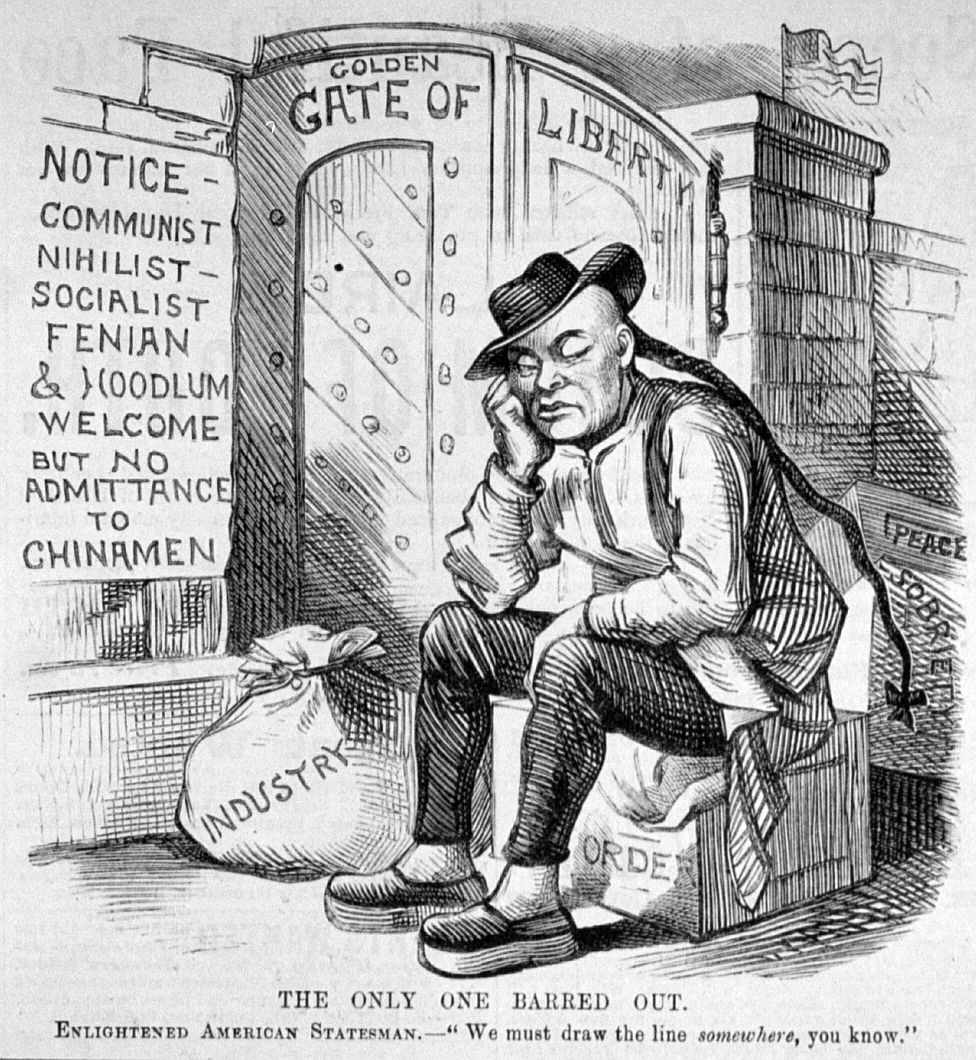

While nearly every immigrant group, except perhaps the English, faced some degree of prejudice and discrimination, the Chinese (and other Asians) faced it on a scale only experienced in similar measure by Indigenous, Latine, and African Americans. And, as was the case for these other groups, hatred of them was fueled not just by a sense of Anglo-nationalism, but also by a virulent ideology of white supremacy. In the 1870s, the situation for Chinese immigrants turned decidedly worse than it had been up until then. In 1873, for instance, the United States and Europe experienced a severe financial crisis and slipped into an economic depression. It is a sad truth that multi-ethnic nations are particularly susceptible during economically difficult times to the blaming of outsiders for their troubles, and this is exactly what happened to the Chinese during the last quarter of the 19th century.

While it had been relatively easy for Chinese migrants to enter the country during the 1850s and 1860s, it became dramatically more difficult after the passage of the Page Act of 1875, which marked the beginning of an era of restrictive federal immigration laws. Before its passage, U.S. borders were largely open to immigrants from anywhere in the world. But the Page Act was specifically designed to prevent the immigration of two groups in particular: contract laborers and Chinese women. The latter restriction was put in place out of a belief that any Chinese woman that entered the country was a prospective prostitute. This, of course, further exacerbated the gender disparities and impeded the formation of Chinese families in America.

Seven years later, Congress passed an even more restrictive law, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This law prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was subsequently renewed and strengthened in 1892 with the passage of the Geary Act, and it was made permanent in 1902. However, the exclusion acts did not close off Chinese immigration completely, as certain classes of people—merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplomats—were still able to enter the country, but it did lead to a steep decline in the Chinese population, which fell from 105,465 in 1880 to 61,639 in 1920 (Tong 2000).

Unfortunately, the anti-Chinese forces in the latter decades of the 19th century were not satisfied with mere legislation. They wanted to drive Chinese people out of the country and resorted to terrorism to send that message. During a period of terror now known as “the Driving Out,” violent mobs descended on Chinese communities in Tacoma and Seattle and drove hundreds of Chinese out of their homes and out of town. In Rock Springs, Wyoming, white miners armed with knives, hatchets, and guns marched to Chinatown, robbing and shooting Chinese people along the way. When they reached Chinatown, they burned people’s houses and shot many of the residents as they ran to escape the fire. Similar deeds, too numerous to cover here, were repeated in various Chinese communities throughout the West (Chang 2004).

For their part, Chinese people fought back, particularly against the many discriminatory laws, both state and federal, that had been passed over the years. Although Chinese residents challenged many of the laws in court, they were often not successful in securing favorable outcomes. But Chinese litigants sometimes did win in court. A notable example was Wong Kim Ark, who won a landmark Supreme Court case that would establish the principle of birthright citizenship as a precedent with implications not just for Chinese, but for every child thereafter born on U.S. soil to parents who were not citizens.

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco in 1873 to Chinese merchants living in the U.S. at the time. After a trip to China, Wong Kim Ark was denied reentry to the United States under the Chinese Exclusion Act. However, he challenged the government’s refusal to recognize his legal right to reenter the country. In 1898, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor, affirming that any person born in the United States who is “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” acquires automatic citizenship under the language of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which also guarantees the equal protection of all citizens under the law (Chang 2004: 37–38).

However, seven years later, when an American-born citizen of Chinese descent, Ju Toy, faced the same situation as Wong Kim Ark, he was detained at the port of entry in San Francisco by immigration officials determined to deport him. Ju Toy sued in Federal District Court which ruled in his favor and ordered his release. But the U.S. government appealed the case to the Supreme Court. In an astounding act of inconsistency, given its previous ruling in the Wong Kim Ark case, the Supreme Court ruled that the Secretary of Commerce and Labor, who oversaw immigration, had jurisdiction over such matters, and that the secretary’s decision would be final. American-born Chinese seeking to re-enter the country, regardless of their citizenship status, were not entitled to appeal the decisions of immigration officials to the courts! (Chang 2004).

The Ju Toy decision set off a firestorm of protest in China, where activists organized an embargo on all American goods and businesses until the exclusion policy was repealed. Chinese workers in Shanghai quit working for American companies, moved out of American-owned buildings, and pulled their children out of American schools in China. Chinese businessmen canceled contracts with American firms and boycotted American products. Demonstrators prevented American ships from unloading, and newspapers refused to run American ads. The protests spread from the Canton region to the interior. The boycotts, which went on for a year, caused major damage to American business interests, depriving the United States of roughly $30 to $40 million dollars of trade. Finally, the U.S. government pressured the Qing government to put an end to the boycotts, which it did, but the whole episode led President Theodore Roosevelt to issue an executive order to U.S. immigration officials to put an end, under penalty of dismissal, to their abusive treatment of legally protected classes of Chinese immigrants, i.e., those carrying proper paperwork (Chang 2004).

Ironically, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake was a stroke of good fortune for many Chinese residents of that city, as the fire that consumed San Francisco also destroyed birth and citizenship records. This allowed many immigrants to claim that they had been born in San Francisco. In this way, many China-born residents of San Francisco claimed U.S. citizenship, which in turn enabled them to claim citizenship for their wives in China and their foreign-born children (Takaki 2008). Although this may seem to be a bright spot in the dark history of exclusion, it did not erase the great harm caused to the Chinese community by the long legacy of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which remained in effect all the way up until 1943.

Becoming Chinese American

The beginnings of a unique Chinese American identity began to emerge in the early 20th century out of the collective experiences of a large foreign-born population of Chinese and a small but growing population of American-born Chinese growing up on the margins of two worlds—one traditionally Chinese and the other mainstream American. It was also worked out in the pages of American Chinese-language newspapers that openly debated the issues of the day. To fully appreciate these issues, it is useful to keep in mind the revolutionary forces—historical, technological, economic, and social—against which Chinese people in the United States worked out their identities.

First, there was a revolution in China. In 1912, a nationalist revolution, which had been brewing for years, finally succeeded in sweeping away the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and a republican government was established in China. Although many Chinese people in the United States had advocated for modernization and reform of the Qing Dynasty rather than its overthrow, most people accepted and came to identify with the newly established Republic of China once it came into existence, and they turned their attention to debating the principles that should govern a modern Chinese state. There were those who felt that the Republic of China should continue to be based on traditional Confucian values. The San Francisco Chinatown elite, for instance, tended to take this position. However, there were others who associated Confucianism and many traditional Chinese practices with backwardness, arguing that as long as Chinese people continued to cling uncritically to old customs and traditions, they would continue to be aliens in America (Chen 2002).

The second revolution afoot in the opening decades of the 20th century was an American (and European) social revolution. The so-called Victorian Age, often noted for its social restraint and restrictive approach to gender relations, which particularly constrained women’s freedom, was giving way to the Jazz Age. During the Jazz Age, a mass migration from the country to the city was underway, the economy was expanding, consumerism was on the rise, and young people were rebelling against the social conventions of their parents’ generation. After having joined the workforce during World War I, white women were further exercising their newly experienced independence. Importantly, African American women and poor white women had always had to work for a living, and continued to be marginalized in low-paid, undesirable jobs, as compared to their relatively privileged sisters. The passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919 gave white women the right to vote for the first time, and they wasted no time in exercising their newly acquired political power. American-born Chinese could not help but be attracted to the liberating tendencies occurring in American society. In the same way that Anglo American youth and women were freeing themselves from Victorian values, Chinese American youth and women were often anxious to free themselves from the strictures of the Confucian social order (Chen 2002).

However, as the 20th century dawned, turning away from Confucian ideas was not an easy matter for the greater Chinese community. For one thing, in 1910, 79 percent of the Chinese population in the U.S. had been born in China, and many of them were understandably ambivalent regarding their identities. Indeed, many of them continued to harbor strong nationalist sentiments. For one thing, they still had close ties with friends and family back in China and often sent money to support the folks back home. Moreover, Chinese people in the U.S. had watched the rising nationalism and anti-imperialism in China with great interest and concern. Many saw themselves as part of a larger movement for Chinese modernization, even going so far as to support reforms in China through activism and fundraising. In addition, Chinese people readily joined cultural and social organizations that provided a sense of community and belonging and promoted Chinese culture and language (Chen 2002).

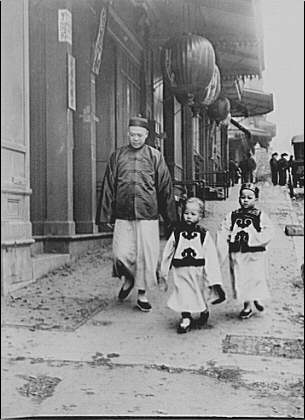

On top of all of this, the fact that the United States had erected barriers to citizenship unlike any that had confronted European immigrants, and the continuing atmosphere of discrimination, humiliation, and exclusion faced by Chinese people in the United States naturally tended to reinforce a sense of Chinese identity and solidarity. And whether out of mere habit or as an expression of nationalistic sentiment, many Chinese people continued to signal their Chinese-ness by wearing Chinese clothing, wearing their hair in a queue, and adhering to many other traditional Chinese practices.

* * *

Despite the fact that such a large proportion of the Chinese community was foreign-born, a sizable American-born Chinese population had also begun to take root in many of America’s major cities (Chen 2002, Rouse 2009). At the same time, America’s metropolitan Chinatowns were becoming very different places compared to their 19th-century precursors. No longer just way stations and service centers for men on the way to and from gold fields, railroads, fisheries, and so on, Chinatowns had become home to women and children too (Takaki 2008). Thus the Chinese Exclusion Act had made it difficult, but not impossible, for Chinese immigrants to establish families.

Meanwhile, Chinese Exclusion Lives On

During the 1920s, the nativist sentiments that had always ebbed and flowed throughout U.S. history were once again on the rise. While the Chinese had faced restrictions on their ability to enter the country throughout the 19th century, the door had always been more or less open to Europeans. Before 1880, however, most European immigrants had come from countries in northern and western Europe, primarily Ireland, Germany, and the United Kingdom. While some of these newcomers, notably the Irish, were not exactly welcomed with open arms, their arrival was tolerated by an expanding nation in need of labor. But after 1880, immigration shifted from northern and western Europe to southern and eastern Europe. When Italians, Russians, and various ethnic groups from Austria-Hungary began arriving in large numbers, nativists considered them undesirable and began agitating for immigration control. The most significant legislation to come out of the uproar was the Immigration Act of 1924, which set quotas on the number of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe.

While the primary aim of the Immigration Act of 1924 was to limit the entry of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, it also tightened the already restrictive laws on immigration from Asia. Whereas in the four years prior to the law’s implementation, more than 20,000 Chinese immigrants had entered the country, from 1924 until after World II, there were never as many as 2,000 Chinese immigrants in any one year. Moreover, the law also barred U.S. citizens of Chinese ancestry from bringing their “alien” Chinese wives, thus reinforcing the already existing imbalance in the sexes. While an average of 150 Chinese women had been legally admitted each year from 1906–1924, between 1924 and 1930, none were admitted. Fortunately, this ban was relaxed somewhat by a 1930 law that permitted Chinese citizens once again to bring their wives, but only if they had married before May 26, 1924, the day the law was enacted. As a result of this provision, from 1931 to 1941, about 60 Chinese women were admitted each year (Daniels 1990).

Weathering the Great Depression

By the 1930s, as the country slid into the worst economic crisis in its history, Chinese Americans were largely concentrated in major cities, usually in racially segregated neighborhoods. Because of the challenges that Chinese communities had been forced to endure in order to survive U.S. exclusion policies, they had become extraordinarily self-sufficient, which helped insulate them from the worst effects of the Great Depression. Long denied access to the formal banking system, “most Chinese businesses had established their own informal credit systems. Aspiring entrepreneurs would borrow money from relatives, or partner with other Chinese immigrants to create a hui, a pool of capital into which they would make regular deposits and out of which loans would be made at mutually agreed rates of interest.” In addition, their longstanding habits of “frugality, reliance on family connections, and avoidance of frivolous debt” also helped Chinese Americans stay afloat throughout the depression (Chang 2004: 201).

Moreover, unlike many other Americans who were reliant on wage labor and therefore vulnerable to being laid off, Chinese Americans often owned small businesses, which gave them somewhat greater control over their own economic circumstances. Of course, none of this means that Chinese Americans were not affected by the Depression. As white Americans lost their jobs, they had less money to spend on services offered by Chinese businesses, such as restaurants and laundries, and this loss of business naturally meant that Chinese families had to get by on less (Chang 2004).

In an effort to bring more money into Chinese communities all across the country, many civic leaders sought to promote tourism as a potential source of cash. Unfortunately, efforts to make Chinatown an exciting destination for tourists often served to spread false and misleading impressions about the Chinese American community. As Iris Chang observed, the strategy in San Francisco Chinatown was to

“make tourists WANT to come, and when they come, let us have something to SHOW them!” The result was a live fantasy version of the “wicked Orient,” exploiting the most debased stereotypes of the Chinese. Tour guides spun tales of a secret, labyrinthine world under Chinatown, filled with narcotics, gambling halls, and brothels, where beautiful slave girls, both Chinese and white, were kept in bondage. They ushered gaping tourists into fake opium dens and fake leper colonies. … In Los Angeles, teenagers earned money after school by pulling rickshaws for white sightseers. In New York City … guides warned visitors to hold hands for safety as they walked through the neighborhood’s streets. They paid Chinese residents to stage elaborate street dramas, including knife fights between “opium-crazed” men over possession of a prostitute” (Chang 2004: 204).

Many Chinatown residents were understandably offended by the spectacles, the ludicrous myths of subterranean communities beneath the streets, and the portrayal of their neighborhoods as places of rampant crime and debauchery. In the end, these depression-era tourism schemes may have brought some extra money into Chinese communities, but they undoubtedly also did major damage to them by painting Chinese people in a negative light and thus, however unintentionally, perpetuating the 19th century Yellow Peril trope, reinforcing many anti-Chinese prejudices that whites already held (Chang 2004).

On the other hand, the 1930s also marked the beginning of a turning point in the way white Americans viewed Chinese people. Changing sentiments were motivated in part by world events and in part, perhaps, by a gradual shift in the way that Hollywood began to portray Chinese people. Before the mid-1930s, for instance, Hollywood tended to rely heavily on the Yellow Peril trope as exemplified by the Chinese evil genius Fu Manchu, a villain intent on conquering the world. However, after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, which was a prelude to the eventual outbreak of World War II in China, Hollywood began producing a series of Chinese-themed films, many of which featured Chinese American performers from the Los Angeles area. According to William Gow, the most influential Hollywood film of the 1930s was The Good Earth, released in 1937. Based on the 1931 novel by Pearl S. Buck, who had grown up in China as the daughter of Christian missionaries, the movie presented a more sympathetic view of Chinese people compared to many of the China-themed movies of the previous decade (Gow 2018).

Besides its thematic significance, however, The Good Earth was also notable for the amount of work it provided for a substantial proportion of the Chinese American community of Los Angeles and the surrounding region. For instance, in making the movie, MGM Studios built an elaborate set that included an entire Chinese village on a 500-acre lot in the San Fernando Valley. As William Gow has noted:

The village featured water buffalo, rice fields, and more than 200 buildings, many imported directly from China. In order to populate this village and other scenes in the film, MGM reportedly employed more than one thousand Chinese American background extras, most from the Los Angeles area. While the film’s producers passed over the well-known [Chinese American] actress Anna May Wong for the film’s lead, and instead hired Louise Rainer … the film did feature an unprecedented number of Asian American performers in speaking roles. … In the midst of the Great Depression, this replica Chinese Village became a site of performance, labor, and economic subsistence for large sections of the Chinese American community … struggling with the worst economic downturn the nation had ever seen” (Gow 2018: 75).

World War II and the Beginning of the End of Exclusion

After Japan invaded Manchuria in northeastern China in 1931, Chinese Americans watched with growing concern Japan’s persistent efforts to impose itself upon China militarily. For most Americans, the events taking place in Asia seemed remote. Even the full-scale invasion of China by Japan in 1937 failed to elicit much interest from the average American. However, Chinese Americans organized to support China in its resistance to Japanese aggression and to raise U.S. awareness of the danger posed by Japanese imperialism. Led by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), Chinese communities around the country organized national salvation associations. These associations promoted anti-Japanese rallies and boycotts of Japanese-made goods. They also lobbied the U.S. government to place an embargo on the shipment to Japan of raw war materials, such as scrap metal that was being turned into munitions used to kill Chinese. Moreover, major Chinatowns hosted “rice bowl” parties—massive festival-like street events designed to raise money for China’s defense that were attended by hundreds of thousands in cities with large Chinese American populations, like San Francisco, New York and Los Angeles (Chang 2004, Tong 2000).

The image of the Chinese community was already undergoing revision in the 1930s, as discussed in the previous section, and Chinese Americans leaned into that trend in a big way during the years immediately preceding World War II, going to great lengths to differentiate themselves from Japanese people in the minds of white Americans. For example, The Chinese Digest, a weekly newspaper published from 1935 to 1940, engaged in a propaganda campaign to portray Chinese people as average Americans, while at the same time painting the Japanese with the same racist stereotypes that had commonly been applied to the Chinese decades earlier (Tong 2000). That effort got a tremendous boost after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, which Iris Chang has characterized as an event that “transformed the American image of China and Japan—and redistributed stereotypes for both Chinese and Japanese Americans.”

Suddenly the media began depicting the Chinese as loyal, decent allies, and the Japanese as a race of evil spies and saboteurs. After the attack, a Gallup poll found that Americans saw the Chinese as “hard working, honest, brave, religious, intelligent, and practical” and the Japanese as “treacherous, sly, cruel, and warlike”—each almost a perfect fit with one or the other of two popular stereotypes formerly promoted by Hollywood, in characters like Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu” (Chang 2004: 222–223).

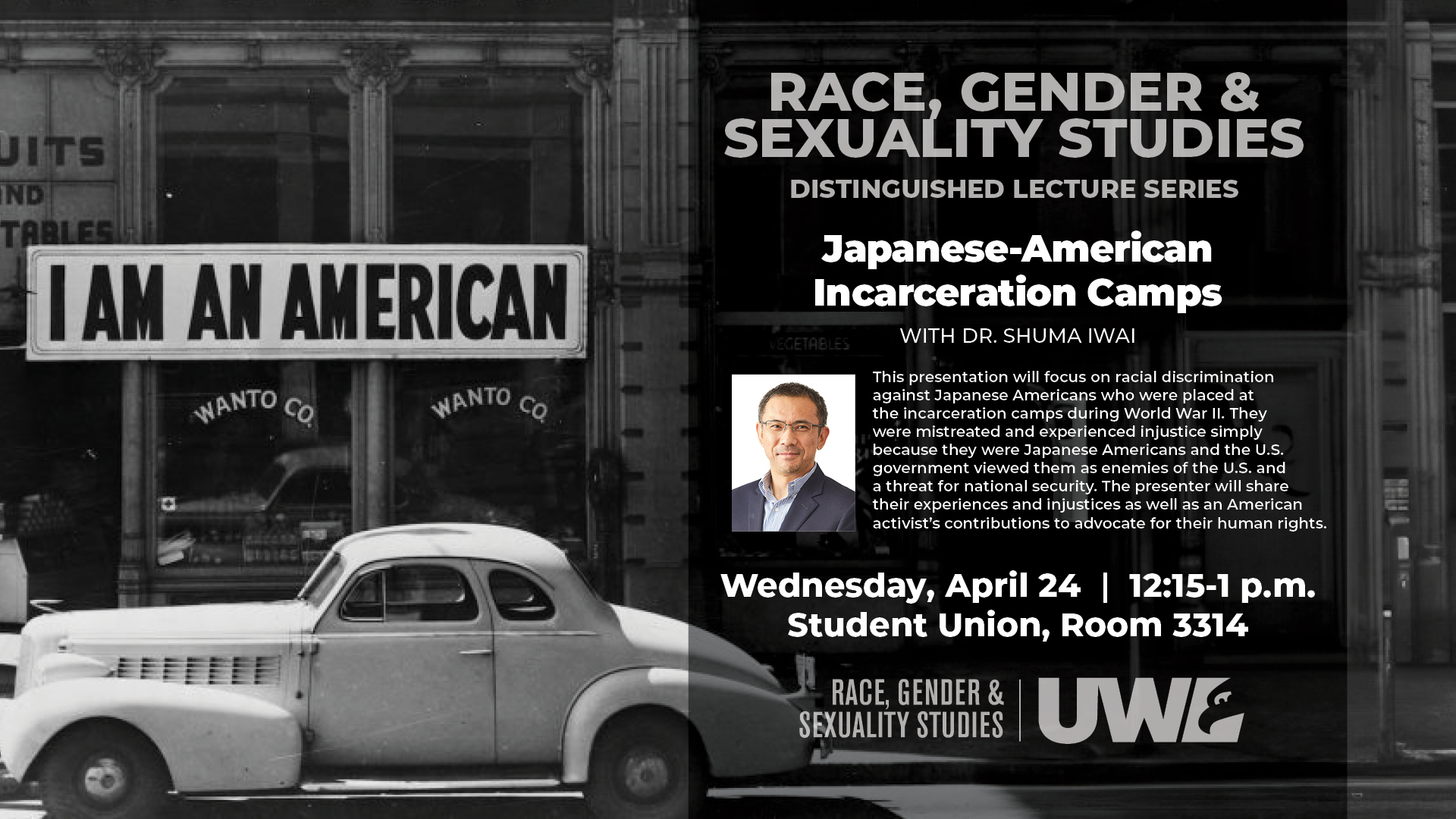

Of course, Japanese Americans did not deserve to have these racist stereotypes attached to them any more than Chinese Americans had decades before, but unfortunately, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans fell victim to a national paranoia in which their loyalty to the United States was questioned, and roughly 120,000 people of Japanese descent were indiscriminately and unjustly rounded up and removed to internment camps.

* * *

The 1940s brought the most significant changes in status that Chinese people had ever experienced in America. For one thing, in 1940, “the percentage of U.S.-born Chinese surpassed that of foreign-born immigrant Chinese” for the first time in the hundred-year history of Chinese immigration. “Thus a majority of the Chinese in America had grown up in America” (Chang 2004: 221), and as a result, Chinese Americans had become more assimilated than ever before. Moreover, the entry of the U.S. into World War II as an ally of China helped to improve the average American’s opinion of Chinese people generally (Tong 2000). To be sure, prejudice and discrimination directed at Chinese Americans did not just suddenly disappear, but the outbreak of World War II required the mobilization of the entire American population, and the visible participation of Chinese Americans helped lessen the extent to which they faced the most egregious forms of racial bias.

The booming U.S. wartime economy also provided Chinese Americans with job opportunities unlike any they had experienced before. With the U.S. facing a profound labor shortage, many Chinese Americans that had been previously confined to low-wage service work in the restaurants and laundries of Chinatown were able to find work in the industrial sector outside of Chinatown. Many landed jobs in shipyards and aircraft factories at union wages and with benefits. Those with advanced education “landed positions as engineers, scientists, and technicians” in the growing high-tech sector. Many Chinese American women found job opportunities outside of Chinatown as “secretaries, clerks, and assistants for government contractors.” The U.S. government also recruited women as air traffic controllers and photo interpreters in the Air WACs (Women’s Army Corps), and others found opportunities in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps (Chang 2004: 232–233). Furthermore, about 22% of adult Chinese males served in the military, and perhaps surprisingly, while they didn’t avoid racism entirely, they served in integrated units, unlike African Americans who were placed in segregated units (Tong 2000: 69–70).

Finally, for many people, both Chinese and non-Chinese, World War II highlighted a hypocrisy in American wartime rhetoric that condemned Nazi racism abroad while ignoring America’s own racism and xenophobia as exemplified by the many anti-Chinese immigration policies enshrined in American law. With China and the United States now allied in the war effort, the United States faced increasing pressure to repeal Chinese exclusion laws (Tong 2000).

The tipping point was reached two years after the U.S. and the Republic of China became official allies, when Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943—also known as the Magnuson Act. The new law allowed Chinese immigration to the U.S. for the first time since the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and it permitted Chinese nationals already residing in the U.S. to become naturalized citizens. On the other hand, the Magnuson Act left in place a discriminatory quota system as prescribed by the Immigration Act of 1924. Under this system, Chinese admissions to the U.S. were capped at 105 persons per year. The Magnuson Act was thus more symbolic than substantive in addressing historical injustices towards Chinese people, although it was at least a small step forward (Tong 2000).

Perhaps more significant in practice was the 1945 War Brides Act, which permitted military servicemen to marry overseas and bring their foreign-born wives to the United States. Because of the historical imbalance in the male-female ratio in the American Chinese community (three men for every one woman), many Chinese American servicemen decided to find marriage partners in China. Between the enactment of the War Brides Act in 1945 and its expiration in 1949, nearly “six thousand Chinese American soldiers went to China and returned with brides. (Under the War Brides Act, brides were not subject to the quotas established by the Immigration Act of 1924.) As a result, about 80% of all new Chinese arrivals were women. Moreover, as the newlyweds began having children, there was a baby boom, and “during the 1940s, the ethnic Chinese population in the United States soared from 77,000 to 117,000 (Chang 2004: 234).

Changing Chinese American Demographics

While the U.S. began loosening immigration policies in the 1950s, as discussed above, the 1965 Immigration Act changed U.S. immigration policy more than any legislation since the Immigration Act of 1924. The 1965 law ended the national origins formulas that had, throughout the 20th century, granted larger quotas to immigrants from northern and western Europe while keeping the quotas low for nationalities perceived as “less desirable” (e.g., southern and eastern Europeans and Asians). Although the 1965 Immigration Act still imposed quotas, most countries were now subject to the same quotas, which reflected a preference system that prioritized family reunification and employment-based immigration.

These changes in U.S. policy led to “a tenfold increase in the Chinese American population,” from less than a quarter of a million (237,292) in 1960 to more than 2.8 million (2,879,636) in 2000. The focus on family unity primarily benefited the earlier working-class immigrants from Guangdong Province who were able for the first time to bring relatives that had previously been excluded by U.S. policies. On the other hand, the focus on professional preferences favored a different class of Chinese, a highly educated upper-middle-class immigrant, often from Taiwan or Hong Kong (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 316).

The new immigration rules also hastened a trend already in the making, the bifurcation of the Chinese American population into two distinctive subgroups: a more highly educated, professional class better able to position its children for educational and economic success, and a working class, more likely to raise children whose possibilities were limited by difficult economic circumstances and a relative lack of social capital. The former group would end up contributing to the “model minority” myth, which we will discuss in more detail later in the chapter.

The Asian American Movement

Emergence of a New Identity

As discussed elsewhere throughout this book, the 1960s and ’70s were turbulent decades marked by the rise of robust Indigenous, Latine, and Black social movements, as well as an anti-war movement, women’s movement, and gay liberation movement, not to mention decolonization movements around the world. Although less well-known perhaps than the Black Power Movement, the Chicano Movement, or the Red Power Movement, the Asian American Movement coincided with, drew inspiration from, and worked in solidarity with all of these other movements. Like the other movements, the Asian American Movement was animated by the coming of age of the post-World War II, baby-boom generation that brought not only a surge in college enrollment but also assembled the most ethnically diverse cohort of youth ever to attend college up until that time (Maeda 2012, Tong 2000).

As Chinese American baby boomers joined diverse groups of politically informed young Americans on college campuses, some were inspired to take part in the various social movements they were exposed to, including the student, free speech, anti-war, or civil rights movements. Their encounter with Black student activists, who were especially persuasive in persuading all minorities to reject the false consciousness of white supremacy, proved to be particularly formative.

It was in this context that the term “Asian American” came into being as a deliberate effort to cultivate a pan-Asian consciousness that recognized the shared challenges faced by individuals of Asian descent in the United States. The term was coined by a Japanese American professor, Yuji Ichioka, when he and his Chinese American spouse Emma Gee, a fellow political activist, co-founded the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) in May 1968 at the University of California, Berkeley. Until then, the most politically active “Asian Americans”—mainly Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos—had never really seen themselves as belonging to a single group, and although coalition building would be challenging, coalition partners would soon come to appreciate the political leverage to be achieved by bridging cultural divides and taking collective action (Maeda 2012, Tong 2000, Kwong & Miščević 2005).

One of the first actions of the AAPA was “to take part in the coalition with the Black Panther Party and antiwar groups in support of the new Peace and Freedom Party—an alternative to the two party establishment.” This “was the first time that the idea of ‘Asian Americanism’ was used nationally to mobilize people of Asian descent” Kwong and Miščević 2005: 268).

Asian Anti-war Movement

In the mid-1960s, American involvement in the Vietnam war had drawn the attention of anti-war activists. By 1967, a broad coalition known as the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE) had formed. Leaders of the mainstream movement organized thousands of nationwide anti-war demonstrations based on a simple message with which it was assumed everyone could agree: “End the war, withdraw American troops, bring our boys home.” The racial implications of the Vietnam war never dawned on most white Americans (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 268).

“African-Americans, however, … understood the the war’s racial aspects all too well.” In 1965, when news of a classmate’s death in Vietnam reached young Blacks in Mississippi, they printed leaflets: “No Mississippi Negroes should be fighting in Vietnam for the white man’s freedom, until all the Negro people are free in Mississippi.” In 1967, world heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali refused to be inducted into the military to fight what he called a “white man’s war,” declaring, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.” For this, he was stripped of his boxing title (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 269).

The racial aspects of the Vietnam War were also not lost on Asian Americans. As Kwong and Miščević (2005) observed:

From the very beginning, Asian Americans had a visceral reaction to the war—they could not look at the pictures of carnage at My Lai without noticing that American troops were killing and maiming unarmed, unresisting women and children with faces like their own. During the [1971] Winter Soldier investigation into U.S. war crimes in Vietnam, Scott Shimabukaro of the Third Marine Division testified that Vietnamese were referred to as “gooks” and that “military men have the attitude that a gook is a gook … they go through brainwashing about the Asian people being subhuman—all the Asian people—I don’t mean just the South Vietnamese … all Asian people.” Down in the trenches, GIs echoed the attitude through the expression “The only good gook is a dead gook.” … [In the end], one could not help but make a connection between the callous American attitude toward the Vietnamese and the treatment of Asian Americans in the United States” (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 269).

Consequently, Asian American anti-war activists generally found themselves at odds with the customary MOBE slogan, “Bring the Boys Home,” which they found blind to the humanity of Vietnamese people. In contrast, Asian American activists were more likely to express their opposition to the war with rallying cries such as, “We don’t want your racist war,” and “Stop killing our Asian brothers and sisters.” After holding a symposium in San Francisco, called Towards an Asian Perspective on Vietnam, Asian American activists began holding “demonstrations under their own banners,” or participating “in the third world rallies with African Americans and Latinos.” Meanwhile, efforts to get mainstream MOBE activists to recognize Asian American concerns were often dismissed by white activists as divisive, and Asian Americans were sometimes “left off the roster of speakers at rallies.” Such slights tended to prompt Asian Americans “to conclude that the supposedly progressive white activists were racist” (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 270–271).

Challenging the Education System

Asian American college students also joined Black, Indigenous, and Chicano students in challenging the Eurocentric curricula of American universities. These challenges first took root at San Francisco State College (now California State University at San Francisco), “where the majority of the students came from working class families.” In 1966, African American students had called for the “admission of more economically … disadvantaged students and for a black-controlled Black Studies Department” (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 273–274).

University administrators, of course, failed to meet student demands, and in 1968 a coalition of African American, Chicano, Indigenous, and Asian American students—calling themselves the Third World Liberation Front—organized a general student strike. The students’ demands were for “relevant and accessible education for their communities, including open admissions, community control and redefinition of the education system, as well as the establishment of ethnic studies and a curriculum that reflected the participation and contribution of groups previously omitted from what was taught as American history.” The student strike at San Francisco State College went on for five months, sparking similar strikes at other universities across the country, including UC Berkeley, UCLA, and the City College of New York. In the end, San Francisco State College became the first university to establish ethnic studies programs, including Asian American studies. Eventually, other major universities would follow suit (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 273–274).

The establishment of ethnic studies programs in American institutions of higher education led to many advances in American historiography and in the social sciences. In time, this new knowledge would trickle down to elementary and secondary schools, where the contributions of Asian Americans and other ethnic groups to the country’s history were barely ever mentioned. For example, a study of 300 elementary and secondary school social studies textbooks conducted by a San Francisco board of education found that 75 percent of the books did not mention the Chinese at all. Although the hard work of student activists during the civil rights era laid a foundation for the liberalization of American education, their efforts were often met with fierce resistance and setbacks (Kwong & Miščević 2005: 274). Despite many successes, the struggle on the part of many ethnic groups for inclusion in the national narrative remained and still remains a challenge today.

* * *

Chinese American activists also played a significant role in the growth of the bilingual education system in the United States. During the late 60s and early 70s, the San Francisco Bay Area was a hotbed of political activity, as we have already seen, with large numbers of American-born Chinese attending universities such as the University of California at Berkeley and San Francisco State College. Fired up by their newfound commitments to civil rights, many of these students returned to their old Chinatown neighborhoods, determined to help American-born Chinese as well as a new immigrants fight against discrimination and increase their access to equal opportunites (Chang 2004).

As Chang has recounted:

During the 1960s, Chinese immigrant parents in San Francisco had complained that their children were unable to follow classroom instruction in English. The Chinese for Affirmative Action, founded in 1969 to fight racial discrimination against Chinese and other Asian Americans, helped ethnic Chinese students file a class action lawsuit against education officials to get them to address their language needs in the public schools. The case eventually reached the Supreme Court, which in 1974, in Lau v. Nichols, overruled a lower court decision …(Chang 2004: 273).

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court declared that “the lack of supplemental language instruction in public school for students with limited English proficiency violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” The Lau v. Nichols decision was a landmark Supreme Court decision that laid the foundation for other historic language reforms in the American education system.

Myth of the Model Minority

The “model minority” myth is a stereotype that characterizes certain Asian American groups, particularly those of East Asian descent, as exceptionally successful, hardworking, and academically high-achieving. Although the stereotype had begun to take shape during the 1960s and 70s, it was increasingly popularized during the 1980s by the national news media. For example, many stories appeared throughout the decade highlighting the educational triumphs of Asian Americans, profiling those who had won National Merit Scholarships or the Westinghouse Science Talent Search. At the same time, the rise of a relatively affluent Chinese professional class with the financial resources to send their children to the best schools meant that many Chinese American students were routinely entering prestigious Ivy League schools and highly selective state universities in disproportionate numbers (Chang 2004).

However, the model minority myth is a flawed and harmful exaggeration. First of all, it is not true that all Chinese Americans are academically high achievers. Indeed, academic success varies significantly among different Chinese American subgroups, with factors such as socioeconomic status, access to quality education, and individual circumstances playing a significant role. So while some Chinese Americans, more often those from more affluent backgrounds, may excel academically, their more disadvantaged peers may struggle against language barriers, limited access to resources, and personal circumstances that make high levels of academic achievement less likely. The stereotype of the academic high-achiever is harmful to young Chinese Americans in other ways as well, placing immense pressure on them to meet unrealistically high expectations, which can lead to mental health issues like anxiety and depression (Tong 2000).

Another aspect of the model minority myth is the idea that Chinese Americans are unusually successful, economically speaking. However, Chinese Americans are not necessarily more economically secure than white Americans, as some statistics might be interpreted as suggesting. For instance, while data collected in 1990 indicated that Chinese Americans had average family incomes ranging from $4,000 to $5,000 higher than that of whites, the fact is that Chinese Americans tend to live in high-cost-of-living states and often have more family members working, resulting in lower real incomes per person (Tong 2000).

Finally, by portraying Asian Americans, including Chinese Americans, as uniformly successful and implying that their achievements are solely the result of hard work and cultural values, the myth reinforces harmful stereotypes about other minoritized groups, such as Blacks, Native Americans, or Latines. The myth implies that those who do not achieve similar success are somehow lacking in effort or cultural values, unfairly placing the blame on individuals rather than addressing systemic inequalities (Tong 2000).

- This chapter is adapted from Who Are We? by Nolan Weil, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ↵