15 Ability

Like race, gender, and sexuality, ability too is socially constructed. Recall that social constructionism doesn’t mean that differences don’t exist, but rather that the meaning and values that society attaches to those differences are the constructed part. One simplified way to understand what it means to say that ability and disability are socially constructed is to imagine a building with stairs going up to the entrance. The only way to enter this building is to walk up the stairs, and therefore anyone using a mobility device such as a wheelchair is unable to enter that building. The social model of disability emphasizes that the problem here is not that someone uses a wheelchair, but instead that the building does not have a ramp or an elevator, or does not create access for people who need mobility devices like wheelchairs. The social model of disability, in other words, locates the problem in the lack of accessible infrastructure, rather than in the person who has different access needs (whether those needs be physical or mental). Here we define disability as: having a physical or mental condition that may limit movement, senses, or activities (including, for example: anxiety, depression, ADHD, diabetes, arthritis, low vision).

Remember in the “Identity Terms” section of Unit 1, we also learned the term “temporarily able-bodied” or TAB. Disability activists often refer to people as TABs because, as the social model of disability helps us understand, all people will need access tools at different times in our lives, and there are a wide variety of reasons why someone might always be, might become, or might remain, disabled. To continue with the wheelchair example, someone could need a wheelchair because they were born with a congenital disability that prevents them from walking. Another wheelchair user might have been in a car accident and lost both legs, later in life. You might have had surgery on your foot and needed a wheelchair or knee-scooter for a few months. Or think of war veterans, who may return home with injuries and amputations that result in them needing mobility devices. And of course the elderly need walkers, canes, or wheelchairs due to the difficulty of walking that comes with old age. This variety extends to mental and invisible disabilities as well. (An example of a mental disability is difficulty focusing, whereas an example of an invisible disability might be something like Crohn’s disease.)

Why does society label some forms of disability “normal,” such as those that come with accidents and old age, while labeling other forms of disability “abnormal,” such as cerebral palsy or dyslexia? Why design a building with exterior stairs that make the building inaccessible to people who use wheelchairs? Or who happen to be on crutches? Or who are pushing a stoller? These are social decisions that are somewhat arbitrary and based in unequal power relations. The science of eugenics (discussed further in Unit III), which was hugely popular across the U.S. and Europe in the early 20th century, asserted that people with disabilities were “impure” and undesirable (alongside racialized people and who we would today call the LGBTQ+ community) (Panofsky 2014). People with disabilities were forcibly sterilized well into the 20th century, in addition to being institutionalized and otherwise discriminated against socially, politically, and economically. We know today that there is nothing inherently wrong with a person who needs a mobility device or a learning aid, for whatever reason, however the stigma of being disabled has yet to wear off. People with disabilities continue to face discrimination, harassment, and bullying in schools, workplaces, and even within their own families (Clare 2014).

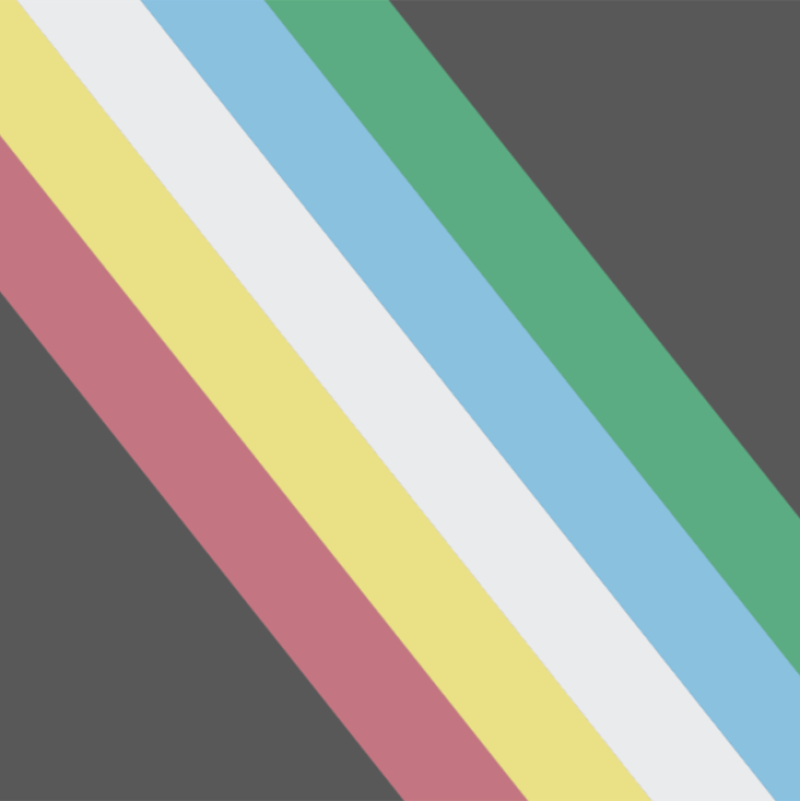

Did you know there is a disability pride flag?

As this brief history of the disability pride flag explains:

Each color stripe has a meaning:

- Red – physical disabilities

- Gold – neurodiversity

- White – invisible disabilities and disabilities that haven’t yet been diagnosed

- Blue – emotional and psychiatric disabilities, including mental illness, anxiety, and depression

- Green – for sensory disabilities, including deafness, blindness, lack of smell, lack of taste, audio processing disorder, and all other sensory disabilities

The faded black background [is for] mourning and rage for victims of ableist violence and abuse. The diagonal band cuts across the walls and barriers that separate the disabled from normate society, also representing light and creativity cutting through the darkness.

To learn more about disability justice, take RGS 353 “The Disability Experience in the Contemporary World”

Here we define disability as: having a physical or mental condition that may limit movement, senses, or activities (including, for example: anxiety, depression, ADHD, diabetes, arthritis, low vision). Credit to Kerrigan Trautsch, RGSS Class of 2025