13 Race

In the context of the United States, there is a binary understanding of race as either Black or white.[1] This is not to say that only two races are recognized, just to say that these are the constructed “oppositional poles” of race. What do we mean by race? More than just descriptive of skin color or physical attributes, in biologized constructions of race, race determines intelligence, sexuality, strength, motivation, and “culture.” These ideas are not only held by self-proclaimed racists, but are woven into the fabric of American society in social institutions. For instance, prior to the 20th century, people were considered to be legally “Black” if they had any African ancestors. This was known as the one-drop rule, or the rule of hypodescent, which held that if you had even one drop of African “blood,” you would have been considered Black. The same did not apply to white “blood”—rather, whiteness was defined by its purity. Even today, these ideas continue to exist. People with one Black and one white parent (for instance, President Barack Obama) are considered Black, and someone with one Asian parent and one white parent is usually considered Asian.

Examples of Racial Formation: the rule of hypodescent (“one-drop”) vs. blood quantum (“one-quarter”)

Comparing how African Americans and Native Americans were racially categorized in the 19th century U.S. offers a striking example of the fiction of race as a biological category, or the social processes of racial formation. Whereas someone in the U.S. with one Black descendant was automatically labeled African American, the U.S. government did not necessarily allow someone with a Native ancestor to be considered Native American. In other words, while U.S. social institutions made it “easy” to be categorized as African American, these same institutions made it difficult for Native Americans to identify (or be identified) as Native Americans. Beginning in the 19th century, the U.S. federal government developed the measure of “blood quantum” to determine who was Native American (Garroutte 2001). Many tribal nations eventually adopted this blood quantum approach, despite its problematic origins, though in different ways. Today, Native Americans typically need to prove that they are at least “one-quarter” Native to receive tribal citizenship or membership, however this process varies by tribal nation. Some tribes continue to use the 1/4 blood quantum fraction to determine tribal membership, some use blood quantum but employ different fractions, some allow for 1/4 only if the entirety of that fraction is from the same tribe (for example 1/4 Navajo as opposed to combining 1/8 Pueblo and 1/8 Hopi), some require paternal descent, some maternal descent, and some—almost one-third of tribes—don’t use blood quantum at all as a measure of tribal citizenship. As Garroutte writes:

Such modern definitions of identity based on blood quantum closely reflect nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century theories of race introduced into indigenous cultures by Euro-Americans. These understood blood as quite literally the vehicle for the transmission of cultural characteristics: “‘Half-breeds’ by this logic could be expected to behave in ‘half-civilized,’ i.e., partially assimilated, ways while retaining one half of their traditional culture, accounting for their marginal status in both societies.” Given this standard of identification, full bloods tended to be seen as the “really real,” the quintessential Indians, while others were (and often continue to be) viewed as Indians in diminishing degrees. These theories of race articulated closely with political goals characteristic of the dominant American society. The original stated intention of blood quantum distinctions was to determine the point at which the various responsibilities of that dominant society to Indian peoples ended. The ultimate and explicit federal intention was to use the blood quantum standard as a means to liquidate tribal lands and to eliminate government trust responsibility to tribes along with entitlement programs, treaty rights, and reservations (Garroutte 2001: 225, emphasis added).

- Given the “original stated intention of blood quantum distinctions” described above, why did the U.S. federal government want to make it more difficult to be categorized as Native American, requiring one-quarter Native ancestry, for instance? (Hint: think about land)

- By contrast, why, in the 19th century U.S., would the federal government have wanted to make it relatively easy to categorize people as African American, requiring only “one drop” of so-called Black blood? (Hint: think about labor)

This 2018 “op-doc” from the New York Times shares important perspectives from various Indigenous peoples of the Americas, on the topic of racial formation.

While “blood” and “blood quantum” seem like biological terms, in reality there is no such thing as Black or Native blood (nor can any other racial categories be identified via blood)[2]. In 2003, PBS released a highly informative docuseries entitled Race: The Power of an Illusion; the first episode helps dispel the persistent myth that different racial categories have fundamentally different human genetics. In fact, there is more genetic variation between members of the same racial group, or intraracial variation, than across members of different racial groups, or interracial variation. Many cultural ideas of racial difference have been (and continue to be) justified by the misuse of science. White scientists of the early 19th century set out to “prove” Black racial inferiority by studying supposed biological differences. Most notable were studies that suggested African American skulls had a smaller cranial capacity, contained smaller brains, and, thus, less intelligence. Later studies revealed both biased methodological practices by scientists and findings that brain size did not actually predict intelligence. The practice of using science in an attempt to support ideas of racial superiority and inferiority is known as scientific racism.

Race as a “Metric of Animality”

Since the time of Aristotle, Western philosophers have imagined the universe as organized into a “ladder of life,” or scala naturae, which early Christians, during the European Middle Ages, developed into the concept of the “great chain of being.” God was placed at the top of this hierarchical scale, followed by angels, man (back then “man” referred to all humanity), the so-called higher animals, such as mammals, then so-called lower animals, such as reptiles, next plants, and finally down to geological features like rocks or soil. This hierarchical conception of life persisted well into modern history. European philosophers and scientists of the late 18th century and early 19th centuries, for example, believed in polygenism, which is the belief that different human “races” constitute different human species (Zuberi 2001). Within the human category of the “great chain of being,” these European elites further constructed a sub-hierarchy, based upon racial categories, placing themselves at the top of the human species hierarchy, while relegating people of African descent to the lowest rung of the “ladder.” Africans were not only a different species of human, but also a lesser species of human, according to early 19th century European culture.

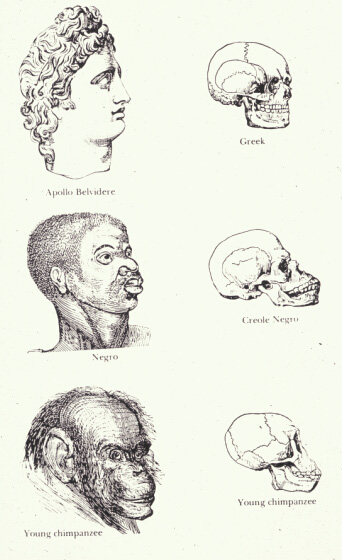

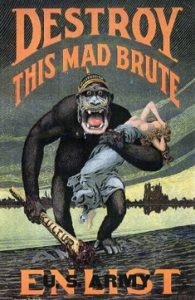

But in 1859, British naturalist Charles Darwin published his famous book Origin of Species, in which he explains the theory of evolution by natural selection, proving that all humans descend from the same primate ancestor, otherwise known as monogenism, meaning there is only one human species. The Origin of Species and Darwin’s theory of evolution caused quite a scandal in its day, in no small part because Europeans had long justified their enslavement of, among other forms of violence against, racialized peoples, by claiming that Africans and Aboriginals and Asians were “subspecies” of human (Anderson 2006). Unfortunately, even the eventual, widespread acceptance of monogenism did not spell the end of the “chain of being.” Rather than throw out their racist ideas of different (and ranked) human species, European, and later, Anglo American, scientists simply changed their labels. Different human species became different human “races,” and the notion that these races are hierarchically ordered remained in place. In other words, Europeans moved to characterizing people from the African, American, and Asian continents as less evolved, lower on an evolutionary scale, and hence still “lesser” forms of human, even if of the same species. European scientists further stretched Darwin’s theory of evolution and monogenism to accommodate the Medieval chain of being; they conceptualized people of African descent as the “missing link” in the “chain” connecting humans with apes (Keel 2018), as the 1857 drawing below, titled “Indigenous Races of the Earth,” cruelly illustrates.

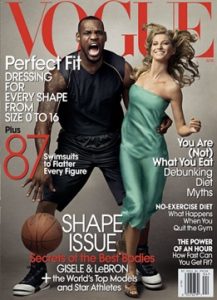

In her 2015 book Dangerous Crossings, political scientist Claire Jean Kim argues that even today, race remains a “metric of animality” in the U.S., as racialized people continue to be animalized in dominant culture, depicted as less human and more animal-like than their white counterparts. Kim’s historical and contemporary archive documents how people of African descent are most commonly, grotesquely stereotyped as apes or gorillas, whereas Asians tend to be animalized as snakes and insects, for instance. How does learning this history of the “chain of being” make you re-think your analysis of the controversial Vogue cover with LeBron James, discussed in Unit 1? (And if you’re interested in learning more about the intersections of science, race, sex, and animality, take RGS 303 “Sex, Race, and Species: Critical Animal Studies”).

Traces of scientific racism remain evident in more recent “studies” of Black Americans. These studies and their applications are often shaped by ideas about African Americans from the era of chattel slavery in the Americas. For instance, the Moynihan Report, also known as “The Negro Family: A Case for National Action” (1965) was an infamous document that claimed the non-nuclear family structure found among poor and working-class African American populations, characterized by an absent father and matriarchal mother, would hinder the entire race’s economic and social progress. While the actual argument was much more nuanced, politicians picked up on this report to propose an essentialist argument about race and the “culture of poverty.” They played upon stereotypes from the era of African American enslavement that justified treating Black Americans as less than human. One of these stereotypes is the assumption that Black men and women are hypersexual; these images have been best analyzed by Patricia Hill Collins (2004) in her work on “controlling images” of African Americans— images such as the “Jezebel” image of Black women and the “Buck” image of Black men. Enslavers were financially invested in the reproduction of enslaved children since children born of mothers in bondage would also become the property of owners, so much so that they did not wait for women to get pregnant of their own accord but institutionalized practices of rape against enslaved women to get them pregnant (Collins, 2004). It was not a crime to rape an enslaved person—and this kind of rape was not seen as rape—since enslaved people were seen as property. But, since many people recognized that enslaved African Americans were nevertheless human beings, they had to be framed as fundamentally different in other ways to justify enslavement. The notion that Black people are “naturally” more sexual and that Black women were therefore “unrapable” (Collins 2004) served this purpose. Black men were framed as hypersexual “Bucks” uninterested in monogamy and family; this idea justified splitting up enslaved families and forcing enslaved Black men to impregnate enslaved Black women. The underlying perspectives in the Moynihan Report—that Black families are composed of overbearing (in both senses of the word: over-birthing and over-controlling) mothers and disinterested fathers and that if only they could form more stable nuclear families and mirror the white middle-class they would be lifted from poverty—reflect assumptions of natural difference found in the ideology supporting American slavery. The structural causes of racialized economic inequality— particularly, the undue impoverishment of Blacks and the undue enrichment of whites during slavery and decades of unequal laws and blocked access to employment opportunities (Feagin 2006)—are ignored in this line of argument in order to claim fundamental biological differences in the realms of gender, sexuality, and family or racial “culture.” Furthermore, this line of thinking disparages alternative family forms as dysfunctional rather than recognizing them as adaptations that enabled survival in difficult and even intolerable conditions (Hartman 2016).

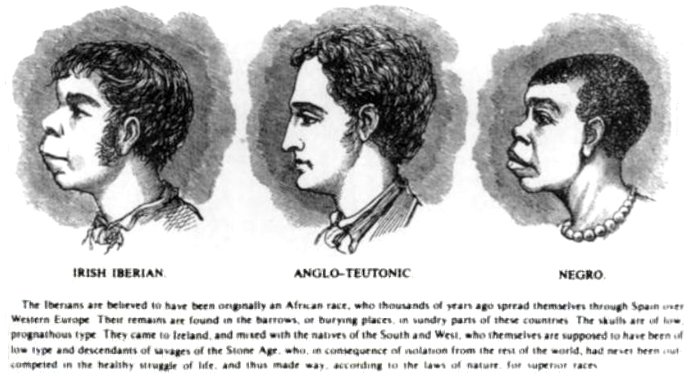

Of course, there are other racial groups recognized within the United States, but the Black/white binary is the predominant racial binary system at play in the American context. We can see how this Black/white binary shapes the construction of other racialized groups if we consider the case of the 19th century Irish immigrant. When they first arrived, Irish immigrants were “blackened” in the popular press and the white, Anglo-American imagination (Roediger 1991). Cartoon depictions of Irish immigrants gave them dark skin and exaggerated facial features like big lips and pronounced brows. They were depicted and thought to be lazy, ignorant, and alcoholic nonwhite “others” for decades.

An illustration from the H. Strickland Constable’s Ireland from One or Two Neglected Points of View shows an alleged similarity between “Irish Iberian” and “Negro” features in contrast to the higher “Anglo-Teutonic.” The accompanying caption reads:

“The Iberians are believed to have been originally an African race, who thousands of years ago spread themselves through Spain over Western Europe. Their remains are found in the barrows, or burying places, in sundry parts of these countries. The skulls are of low prognathous type. They came to Ireland and mixed with the natives of the South and West, who themselves are supposed to have been of low type and descendants of savages of the Stone Age, who, in consequence of isolation from the rest of the world, had never been out-competed in the healthy struggle of life, and thus made way, according to the laws of nature, for superior races.”

Over time, Irish immigrants and their children and grandchildren assimilated into the category of “white” by strategically distancing themselves from Black Americans and other non-whites in labor disputes and participating in white supremacist racial practices and ideologies. In this way, the Irish in America became white. A similar process took place for Italian Americans, and, later, Jewish American immigrants from multiple European countries around the Second World War. Similar to Irish Americans, both groups became white after first being seen as non-white. As sociologists Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer summarized in 2009: “The U.S. justice system has decided dozens of cases in ways that have solidified certain racial classifications in the law. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, legal cases handed down rulings that officially recognized Japanese, Chinese, Burmese, Filipinos, Koreans, Native Americans, and mixed-race individuals as “not White.” In 1897, a Texas federal court ruled that Mexicans were legally “White.” And Indian Americans, Syrians, and Arabians [sic] have been capriciously classified as both “White” and “not White”” (Desmond & Emirbayer 2009: 341). These cases show how socially constructed race is and how this labeling process still operates today. For instance, are Asian Americans, considered the “model minority,” the next group to be integrated into the white category, or will they continue to be regarded as foreign threats?

- Here, we capitalize Black and not white in recognition of Black as a reclaimed, and empowering, identity. ↵

- See Kimberly TallBear's 2013 book Native American DNA for more on the scientific racism of modern-day genetics. ↵