Evaluating Information

Authority

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between various types of authority, including subject expertise, societal position, and personal experience, and recognize the value of or the reasons to seek each type of authority.

- Analyze how authority influences someone’s credibility and understand how factors such as bias or conflict of interest can undermine someone’s credibility.

- Evaluate the authority and expertise of a given author by researching their background, credentials, and publication history using reliable tools and criteria.

Overview

Authority—also called expertise—is about whether someone is a trustworthy source of information on a topic. Knowing how to recognize authority helps you choose the best sources for your research. In this section, you’ll:

- Learn the main types of authority and how to tell them apart

- See how authority affects credibility—and how bias or conflicts of interest can weaken it

- Identify which types of authority matter most in your classes, in your field, and in the workplace

- Practice checking an author’s authority by looking at their background, credentials, and publications

Defining Different Types of Authority

There’s more than one way to be an authority on a topic. Here are three common types:

- Subject expertise: Someone who has done extensive research in a field—often a scientist or scholar—and can provide evidence-based information.

- Societal position: Someone whose role gives them knowledge or influence, like the leader of the NAACP.

- Experience: Someone who has lived through something firsthand, such as a natural disaster survivor sharing their perspective.

These aren’t the only kinds of authority. Education, job history, credentials, and other experiences can also contribute.

Context matters. The most relevant type of authority depends on your situation. For example, if you’re researching Instagram’s effects on young adults’ mental health, a psychologist who has studied this topic would be a strong authority.

Journalists can also be authorities. They’re trained to vet sources, work ethically, and often specialize in topics like politics or sports. This focus gives them insights that most people don’t have. For more information on journalists’ ethics, see the “News Authorship” section of the “News” chapter.

How Authority Impacts Credibility

Having authority doesn’t always mean having credibility. Even experts can be biased or have conflicts of interest.

For example, a scientist might be highly knowledgeable about nutrition, but if they’re being paid to promote a supplement, you should be cautious about trusting their claims without checking other sources.

Or imagine a lawmaker proposing rules to limit Instagram use. They may be an authority on how the law works but not on psychology or mental health. Even if they have a psychology background, their political role could influence what they say—so you’d still want to verify their statements.

Bottom line: Always look at both an author’s expertise and their potential biases before deciding how credible they are.

What Types of Authority are Most Valuable for You

The most useful type of authority depends on your goal. Here’s how it can change in different situations:

In Your Classes

You might draw from all three types of authority that were previously mentioned, so subject experts, people in key positions, and those with personal experience. For example, for a paper on new environmental laws, you could use a politician to explain the law’s details, a scientist to discuss environmental impacts, and a local resident affected by the law to share lived experience.

In Upper-Level Courses

You’ll likely rely more on subject experts in your discipline. Knowing what the leading voices in your field are researching, and how they interpret their findings, will help you engage in deeper, more advanced discussions.

In an Academic Research Setting

If you’re writing a focused research paper, seek out scholarly studies by recognized experts. But don’t overlook personal accounts if they’re relevant. For example, a study on Instagram’s effects on mental health could be enriched by interviews with Instagram users.

In the Workplace

Subject experts remain valuable. Even if you’re not doing original research, staying updated on new developments keeps your knowledge fresh. For example, a practicing psychologist might regularly read new studies to inform client care.

Key takeaway: The best authority depends on the context. Match the type of expertise to the questions you’re asking.

Identifying the Authority/Expertise of a Given Author

The “Evaluating Sources” chapter explains this process in more detail, but here we’ll cover a few quick ways to figure out if an author has real authority on a topic. Think of these steps as your “first pass”—a simple checklist to help you decide whether someone’s expertise makes them a trustworthy source.

Search for the Author’s Credentials

Start by searching the author’s name online to see what credentials they have. A true subject expert often has an advanced degree in the field and has published their own research.

Be careful with sources where the author controls the narrative, like LinkedIn profiles or personal websites. Instead, check neutral or reputable sites—for example, Wikipedia or a faculty page on a university’s website.

As you review their background, ask yourself: “Does their education, work history, and research experience genuinely support their authority on this specific topic?”

See Where They’ve Published

Once you know the author’s background, check where their work appears. For example, if they’re a journalist, do they publish in respected outlets like The New York Times or The Washington Post?

If you’re not familiar with a publication, look it up. Wikipedia entries can help you see whether it’s considered credible and independent. (For instance, in the Wikipedia entry for the Washington Post, it is described as a “newspaper of record” in the U.S., meaning it’s widely regarded as an authoritative source.)

Remember: publishers themselves have authority. Some are more reliable than others, so evaluating them is just as important as evaluating the author. You can learn more about this in the “Step 2: Investigate the Source with Lateral Reading” section of the “Evaluating Sources” chapter.

See Who Else is Citing Them

Another way to check an author’s authority is to see who else is citing their work. In academic research, frequent citations from other scholars often signal that the author’s work is respected and influential.

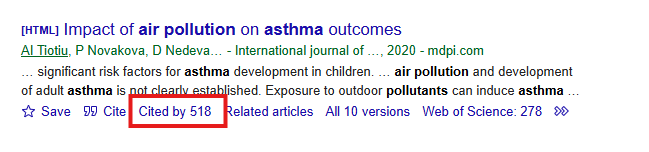

You can find citation counts in many databases, and Google Scholar makes this especially easy:

- Go to Google Scholar (no account needed).

- Search for the article title.

- Then, under the title result, look for the “Cited by” number (See image 1 below).

The “Cited by” number tells you how many other publications have referenced the source.

A high “Cited by” number can suggest strong influence, but keep in mind that new papers may not have many citations yet. Additionally, a citation doesn’t always mean agreement—sometimes people cite work to challenge it.

Checking citations is like seeing how often an author’s voice appears in the bigger scholarly conversation.

Reflection

- Can you think of a time when you assumed someone was an authority on a topic but later realized their credibility was questionable? What did you learn from that experience?

- When working on a research project, how do you decide which type of authority—such as subject expertise, personal experience, societal position, or some other type—is most relevant for your topic?

- How might your understanding of authority and credibility change depending on whether you’re researching for a class assignment, professional work, or personal interest?