Searching for Information

Keywords

Learning Objectives

- Identify the main concepts in a research question that will lead to effective keywords.

- Generate alternative keywords, such as synonyms or related terms.

- Create an effective search strategy using keywords.

Identifying the Main Concepts

Your research question is the foundation for your research process. Once you’ve developed it, the next step is to identify the main concepts within your question. This step is important because most library databases, including Search@UW, don’t respond well to full sentences, like Google does. Instead, they work best when you search using only the essential pieces of your question, which we call “keywords,” “key terms,” or “key phrases.”

To find the main concepts, focus on the core ideas in your question. Skip words like “the,” “why,” “how,” or “affect,” along with most adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and verbs. Keywords are almost always nouns. Ask yourself: what ideas or topics would need to appear in a source for it to be useful to me? Focusing on those core ideas will make your searches more efficient and help you find better, more relevant sources.

Example: Identifying Main Concepts

How can divorce affect a student’s GPA in high school?

Main concepts: “divorce,” “student,” “GPA,” and “high school”

If an information source includes all of the main concepts from your research question, then it is very likely to be relevant and useful to you. It is your job as a researcher to determine what is relevant to your research. (See the “Relevance” chapter.) Be aware that the main concepts from your research question serve as a base to launch your search for information, and the keywords selected to describe your main concepts are likely to evolve during the process.

Alert: Don’t Stop After the First Try!

Examples: Identifying More Main Concepts

How are birds affected by wind turbines?

Main concepts: “birds” and “wind turbines”

Avoid terms like “affect” and “effect” as search terms, even when you’re looking for studies that report effects or effectiveness.

What lesson plans are available for teaching fractions?

Main concepts: “lesson plans” and “fractions”

Stick to what’s necessary. For instance, don’t include:

- Children (nothing in the research question suggests the lesson plans are for children)

- Teaching (not necessary because lesson plans imply teaching)

- Available (not necessary)

Does the use of mobile technologies by teachers and students in the classroom distract or enhance the educational experience?

Main concepts: “teaching methods” and “mobile technology”

Another possibility: “mobile technologies” and “education”

Watch out for overly broad terms. For example, don’t use:

- Educational experience (it misses mobile technology)

- Classroom distractions (too broad because there are distractions that have nothing to do with technology)

- Technology (too broad because the question is focused on mobile technology)

Sometimes your research question itself can seem complicated. Make sure you’ve stated the question as precisely as possible (as you learned in the “Developing a Research Question” section of the last chapter). Then apply our advice for identifying main concepts as usual.

Brainstorming Related Terms

Describing Main Concepts

There’s often more than one way to describe a main concept—and not every source will use the same term for the same idea! For example, take the topic of “genetically modified food.” Though “genetically modified food” is commonly used, terms like “GMO,” “genetically modified organism,” “genetic engineering,” and “genetic modification” are often used by scientists to describe the same thing.

This is a good time to review your main concepts and ask: “Are my keywords too broad or too narrow?” Using a broad term like “genetic engineering” might bring up results that don’t relate specifically to genetically modified food, giving you irrelevant results. Also consider the type of source you’re searching for: scholarly articles often use technical or scientific terminology, while popular sources, like magazines or news articles, tend to use everyday language (e.g., “myocardial infarction” versus “heart attack”).

Brainstorming Alternatives

It’s often helpful to make a list of your keywords along with any alternative or related terms that might be useful during your search. Here are a few ways to find alternative terms:

- Revisit the reference sources you used for background research and see what terminology they use.

- Use a thesaurus to find synonyms.

- Try some initial searches—many databases suggest related terms that can help you refine or expand your search.

Keep in mind, you can always return to this step as your research progresses. It’s common to find new and better keywords after you’ve done a few searches. That said, not every keyword will have alternatives. Some terms are unique and don’t have good substitutes.

| Main Concept/Keyword | Alternative/Related | Alternative/Related | Alternative/Related |

|---|---|---|---|

| divorce | separation | split up | parental conflict |

| student’s GPA | grade point average | academic performance | academic achievement |

| high school | school | secondary school | teenage students |

Avoiding Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is when we look for information that supports what we already believe and ignore anything that doesn’t. It often shows up in how we search.

When choosing keywords, be careful not to build in your own assumptions. For example, searching “why video games make people violent” will lead to very different results than “video games and behavior.” Try to use neutral, balanced terms so you get a full range of information, not just what confirms your opinion.

Example: Confirmation Bias in Search Results

A search for “is rent control unfair to landlords” is likely to get results that describe rent control as unfair to landlords. A better search might be something like “rent control landlords”

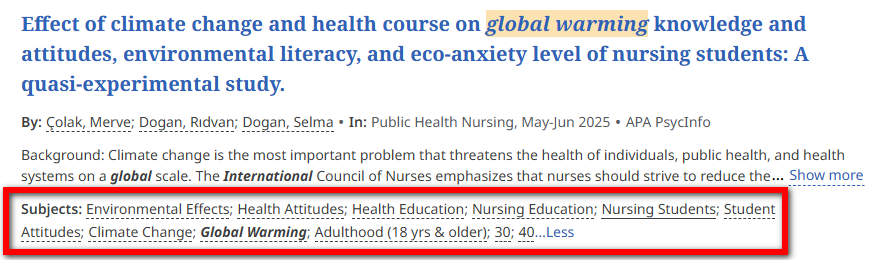

Subject Headings as Keywords

All the searches we have talked about so far have been keyword searches, usually used in search engines. Most library databases also have special terms called “subject headings” that you can search with. Subject headings are standardized terms that are assigned by trained experts. This makes them a great place to get ideas for alternative terms to add to your list of keywords. You can also scan other fields in the database, such as the title or abstract, to get ideas for keywords. This is the language that experts use to talk about the subject. When you get to more advanced research-methods courses in your major, you may learn how to construct specialized searches that use subject headings instead of keywords.

Combining Your Keywords

Once you’ve broken down your research question, identified the main concepts, and listed several keywords (synonyms, narrower terms, and broader terms), you’re ready to start building a search statement. A search statement is a way of combining your keywords using different search strategies to get more precise results. Instead of typing your full research question or just a few random words into a search bar, a well-crafted search statement tells the system exactly what you’re looking for. Think of it like giving a set of instructions to the tool you’re using, whether it’s a library database, Search@UW, or another search platform. The better your search statement, the more relevant and useful your results will be.

Activity: Main Concepts

Reflection

Complete this chart to develop keywords for a topic that you are researching in this class or another class. Add more columns if you have more ideas! Add more rows if necessary for your research questions, although most research questions will have two to three main concepts.

| Main Concept/Keyword | Alternative/Related | Alternative/Related | Alternative/Related |

|---|---|---|---|

Attributions

This chapter contains material adapted from:

- “Library 10” by Cabrillo College Library, used under a CC BY 4.0 license

- “Avoiding Confirmation Bias” from Introduction to College Research by Walter D. Butler, Aloha Sargent and Kelsey Smith, used under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- “Why Precision Searching“; “Main Concepts” & “Related and Alternative Terms” in Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research by Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries, used under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- “Identifying the Main Concepts“; “Brainstorming Related Terms“; & “Creating a Search Statement” in Navigating Information Literacy by Julie Feighery, used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license