Chapter 24 Section 24.7: Gravitational Wave Astronomy

24.7 Gravitational Wave Astronomy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe what a gravitational wave is, what can produce it, and how fast it propagates

- Understand the basic mechanisms used to detect gravitational waves

Another part of Einstein’s ideas about gravity can be tested as a way of checking the theory that underlies black holes. According to general relativity, the geometry of spacetime depends on where matter is located. Any rearrangement of matter—say, from a sphere to a sausage shape—creates a disturbance in spacetime. This disturbance is called a gravitational wave, and relativity predicts that it should spread outward at the speed of light. The big problem with trying to study such waves is that they are tremendously weaker than electromagnetic waves and correspondingly difficult to detect.

Proof from a Pulsar

We’ve had indirect evidence for some time that gravitational waves exist. In 1974, astronomers Joseph Taylor and Russell Hulse discovered a pulsar (with the designation PSR1913+16) orbiting another neutron star. Pulled by the powerful gravity of its companion, the pulsar is moving at about one-tenth the speed of light in its orbit.

According to general relativity, this system of stellar corpses should be radiating energy in the form of gravitational waves at a high enough rate to cause the pulsar and its companion to spiral closer together. If this is correct, then the orbital period should decrease (according to Kepler’s third law) by one ten-millionth of a second per orbit. Continuing observations showed that the period is decreasing by precisely this amount. Such a loss of energy in the system can be due only to the radiation of gravitational waves, thus confirming their existence. Taylor and Hulse shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in physics for this work.

Direct Observations

Although such an indirect proof convinced physicists that gravitational waves exist, it is even more satisfying to detect the waves directly. What we need are phenomena that are powerful enough to produce gravitational waves with amplitudes large enough that we can measure them. Theoretical calculations suggest some of the most likely events that would give a burst of gravitational waves strong enough that our equipment on Earth could measure it:

- the coalescence of two neutron stars in a binary system that spiral together until they merge

- the swallowing of a neutron star by a black hole

- the coalescence (merger) of two black holes

- the implosion of a really massive star to form a neutron star or a black hole

- the first “shudder” when space and time came into existence and the universe began

For the last four decades, scientists have been developing an audacious experiment to try to detect gravitational waves from a source on this list. The US experiment, which was built with collaborators from the UK, Germany, Australia and other countries, is named LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory). LIGO currently has two observing stations, one in Louisiana and the other in the state of Washington. The effects of gravitational waves are so small that confirmation of their detection will require simultaneous measurements by two widely separated facilities. Local events that might cause small motions within the observing stations and mimic gravitational waves—such as small earthquakes, ocean tides, and even traffic—should affect the two sites differently.

Each of the LIGO stations consists of two 4-kilometer-long, 1.2-meter-diameter vacuum pipes arranged in an L-shape. A test mass with a mirror on it is suspended by wire at each of the four ends of the pipes. Ultra-stable laser light is reflected from the mirrors and travels back and forth along the vacuum pipes (Figure 1). If gravitational waves pass through the LIGO instrument, then, according to Einstein’s theory, the waves will affect local spacetime—they will alternately stretch and shrink the distance the laser light must travel between the mirrors ever so slightly. When one arm of the instrument gets longer, the other will get shorter, and vice versa.

Gravitational Wave Telescope.

Figure 1. An aerial view of the LIGO facility at Livingston, Louisiana. Extending to the upper left and far right of the image are the 4-kilometer-long detectors. (credit: modification of work by Caltech/MIT/LIGO Laboratory)

The challenge of this experiment lies in that phrase “ever so slightly.” In fact, to detect a gravitational wave, the change in the distance to the mirror must be measured with an accuracy of one ten-thousandth the diameter of a proton. In 1972, Rainer Weiss of MIT wrote a paper suggesting how this seemingly impossible task might be accomplished.

A great deal of new technology had to be developed, and work on the laboratory, with funding from the National Science Foundation, began in 1979. A full-scale prototype to demonstrate the technology was built and operated from 2002 to 2010, but the prototype was not expected to have the sensitivity required to actually detect gravitational waves from an astronomical source. Advanced LIGO, built to be more precise with the improved technology developed in the prototype, went into operation in 2015—and almost immediately detected gravitational waves.

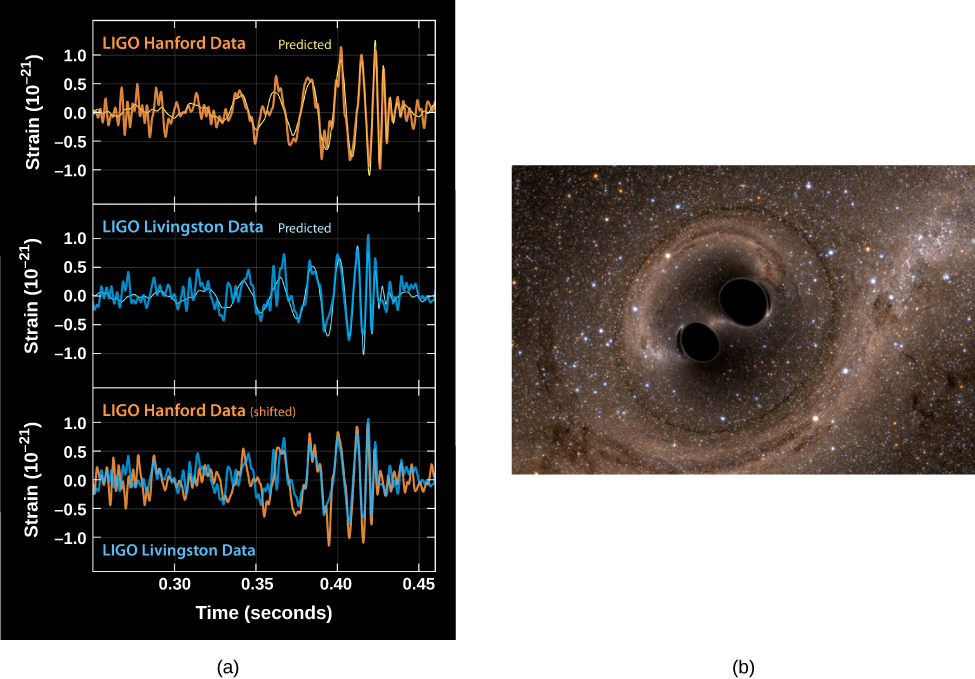

What LIGO found was gravitational waves produced in the final fraction of a second of the merger of two black holes (Figure 2). The black holes had masses of 20 and 36 times the mass of the Sun, and the merger took place 1.3 billion years ago—the gravitational waves occurred so far away that it has taken that long for them, traveling at the speed of light, to reach us.

In the cataclysm of the merger, about three times the mass of the Sun was converted to energy (recall E = mc2). During the tiny fraction of a second for the merger to take place, this event produced power about 10 times the power produced by all the stars in the entire visible universe—but the power was all in the form of gravitational waves and hence was invisible to our instruments, except to LIGO. The event was recorded in Louisiana about 7 milliseconds before the detection in Washington—just the right distance given the speed at which gravitational waves travel—and indicates that the source was located somewhere in the southern hemisphere sky. Unfortunately, the merger of two black holes is not expected to produce any light, so this is the only observation we have of the event.

Signal Produced by a Gravitational Wave.

Figure 2. (a) The top panel shows the signal measured at Hanford, Washington; the middle panel shows the signal measured at Livingston, Louisiana. The smoother thin curve in each panel shows the predicted signal, based on Einstein’s general theory of relativity, produced by the merger of two black holes. The bottom panel shows a superposition of the waves detected at the two LIGO observatories. Note the remarkable agreement of the two independent observations and of the observations with theory. (b) The painting shows an artist’s impression of two massive black holes spiraling inward toward an eventual merger. (credit a, b: modification of work by SXS)

This detection by LIGO (and another one of a different black hole merger a few months later) opens a whole new window on the universe. One of the experimenters compared the beginning of gravitational wave astronomy to the era when silent films were replaced by movies with sound (comparing the vibration of spacetime during the passing of a gravitational wave to the vibrations that sound makes).

By the end of 2017, LIGO had detected four more mergers of black holes. Two of these, like the initial discovery, involved mergers of black holes with a range of masses that have been observed only by gravitational waves. In one merger, black holes with masses of 31 and 25 times the mass of the Sun merged to form a spinning black hole with a mass of about 53 times the mass the Sun. This event was detected not only by the two LIGO detectors, but also by a newly operational European gravitational wave observatory, Virgo. The other event was caused by the merger of 20- and 30-solar-mass black holes, and resulted in a 49-solar-mass black hole. Astronomers are not yet sure just how black holes in this mass range form.

Two other mergers detected by LIGO involved black holes with stellar masses comparable to those of black holes in X-ray binary systems. In one case, the merging black holes had masses of 14 and 8 times the mass of the Sun. The other event, again detected by both LIGO and Virgo, was produced by a merger of black holes with masses of 7 and 12 times the mass of the Sun. None of the mergers of black holes was detected in any other way besides gravitational waves. It is quite likely that the merger of black holes does not produce any electromagnetic radiation.

In late 2017, data from all three gravitational wave observatories was used to locate the position in the sky of a fifth event, which was produced by the merger of objects with masses of 1.1 to 1.6 times the mass of the Sun. This is the mass range for neutron stars (see The Milky Way Galaxy), so in this case, what was observed was the spiraling together of two neutron stars. Data obtained from all three observatories enabled scientists to narrow down the area in the sky where the event occurred. The Fermi satellite offered a fourth set of observational data, detecting a flash of gamma rays at the same time, which confirms the long-standing hypothesis that mergers of neutron stars are progenitors of short gamma-ray bursts (see The Mystery of Gamma-Ray Bursts). The Swift satellite also detected a flash of ultraviolet light at the same time, and in the same part of the sky. This was the first time that a gravitational wave event had been detected with any kind of electromagnetic wave.

The combined observations from LIGO, Virgo, Fermi, and Swift showed that this source was located in NGC 4993, a galaxy at a distance of about 130 million light-years in the direction of the constellation Hydra. With a well-defined position, ground-based observatories could point their telescopes directly at the source and obtain its spectrum. These observations showed that the merger ejected material with a mass of about 6 percent of the mass of the Sun, and a speed of one-tenth the speed of light. This material is rich in heavy elements, just as the theory of kilonovas (see Short-Duration Gamma-Ray Bursts: Colliding Stellar Corpses) predicted. First estimates suggest that the merger produced about 200 Earth masses of gold, and around 500 Earth masses of platinum. This makes clear that neutron star mergers are a significant source of heavy elements. As additional detections of such events improve theoretical estimates of the frequency at which neutron star mergers occur, it may well turn out that the vast majority of heavy elements have been created in such cataclysms.

The detection of gravitational waves opens a whole new window to the universe. One of the experimenters compared the beginning of gravitational wave astronomy to the era when silent films were replaced by movies with sound (comparing the vibration of spacetime during the passing of a gravitational wave to the vibrations that sound makes). We can now learn about events, such as the merger of black holes, that can be studied in no other way.

Observing the merger of black holes via gravitational waves also means that we can now test Einstein’s general theory of relativity where its effects are very strong—close to black holes—and not weak, as they are near Earth. One remarkable result from these detections is that the signals measured so closely match the theoretical predictions made using Einstein’s theory. Once again, Einstein’s revolutionary idea is found to be the correct description of nature.

Because of the scientific significance of the observations of gravitational waves, three of the LIGO project leaders—Rainer Weiss of MIT, and Kip Thorne and Barry Barish of Caltech—were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2017.

Several facilities similar to LIGO and Virgo are under construction in other countries to contribute to gravitational wave astronomy and help us pinpoint more precisely pinpoint the location of signals we detect in the sky. The European Space Agency (ESA) is exploring the possibility of building an even larger detector for gravitational waves in space. The goal is to launch a facility called eLISA sometime in the mid 2030s. The design calls for three detector arms, each a million kilometers in length, for the laser light to travel in space. This facility could detect the merger of distant supermassive black holes, which might have occurred when the first generation of stars formed only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

In December 2015, ESA launched LISA Pathfinder and successfully tested the technology required to hold two gold-platinum cubes in a state of weightless, perfect rest, relative to one another. While LISA Pathfinder cannot detect gravitational waves, such stability is required if eLISA is to be able to detect the small changes in path length produced by passing gravitational waves.

We should end by acknowledging that the ideas discussed in this chapter may seem strange and overwhelming, especially the first time you read them. The consequences of the general theory of relatively take some getting used to. But they make the universe more bizarre—and interesting—than you probably thought before you took this course.

Key Concepts and Summary

General relativity predicts that the rearrangement of matter in space should produce gravitational waves. The existence of such waves was first confirmed in observations of a pulsar in orbit around another neutron star whose orbits were spiraling closer and losing energy in the form of gravitational waves. In 2015, LIGO found gravitational waves directly by detecting the signal produced by the merger of two stellar-mass black holes, opening a new window on the universe.

For Further Exploration

Articles

Black Holes

Charles, P. & Wagner, R. “Black Holes in Binary Stars: Weighing the Evidence.” Sky & Telescope (May 1996): 38. Excellent review of how we find stellar-mass black holes.

Gezari, S. “Star-Shredding Black Holes.” Sky & Telescope (June 2013): 16. When black holes and stars collide.

Jayawardhana, R. “Beyond Black.” Astronomy (June 2002): 28. On finding evidence of the existence of event horizons and thus black holes.

Nadis, S. “Black Holes: Seeing the Unseeable.” Astronomy (April 2007): 26. A brief history of the black hole idea and an introduction to potential new ways to observe them.

Psallis, D. & Sheperd, D. “The Black Hole Test.” Scientific American (September 2015): 74–79. The Event Horizon Telescope (a network of radio telescopes) will test some of the stranger predictions of general relativity for the regions near black holes. The September 2015 issue of Scientific American was devoted to a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the general theory of relativity.

Rees, M. “To the Edge of Space and Time.” Astronomy (July 1998): 48. Good, quick overview.

Talcott, R. “Black Holes in our Backyard.” Astronomy (September 2012): 44. Discussion of different kinds of black holes in the Milky Way and the 19 objects known to be black holes.

Gravitational Waves

Bartusiak, M. “Catch a Gravity Wave.” Astronomy (October 2000): 54.

Gibbs, W. “Ripples in Spacetime.” Scientific American (April 2002): 62.

Haynes, K., & Betz, E. “A Wrinkle in Spacetime Confirms Einstein’s Gravitation.” Astronomy (May 2016): 22. On the direct detection of gravity waves.

Sanders, G., and Beckett, D. “LIGO: An Antenna Tuned to the Songs of Gravity.” Sky & Telescope (October 2000): 41.

Websites

Black Holes

Black Hole Encyclopedia: http://blackholes.stardate.org. From StarDate at the University of Texas McDonald Observatory.

Black Holes: http://science.nasa.gov/astrophysics/focus-areas/black-holes. NASA overview of black holes, along with links to the most recent news and discoveries.

Virtual Trips into Black Holes and Neutron Stars: http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/htmltest/rjn_bht.html. By Robert Nemiroff at Michigan Technological University.

Gravitational Waves

Advanced LIGO: https://www.ligo.caltech.edu/MIT/page/ligo-gw-interferometer. The full story on this gravitational wave observatory.

eLISA: https://www.lisamission.org.

Gravitational Waves Detected, Confirming Einstein’s Theory: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/12/science/ligo-gravitational-waves-black-holes-einstein.html. New York Times article and videos on the discovery of gravitational waves.

Gravitational Waves Discovered from Colliding Black Holes: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/gravitational-waves-discovered-from-colliding-black-holes1. Scientific American coverage of the discovery of gravitational waves (note the additional materials available in the menu at the right).

LIGO Caltech: https://www.ligo.caltech.edu.

Videos

Black Holes

Black Holes: The End of Time or a New Beginning?: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mgtJRsdKe6Q. 2012 Silicon Valley Astronomy Lecture by Roger Blandford (1:29:52).

Death by Black Hole:https://youtube.com/watch?v=h1iJXOUMJpg&feature=shares. Neil deGrasse Tyson explains spaghettification with only his hands (5:34).

Hearts of Darkness: Black Holes in Space: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tiAOldypLk. 2010 Silicon Valley Astronomy Lecture by Alex Filippenko (1:56:11).

Gravitational Waves

Journey of a Gravitational Wave: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FlDtXIBrAYE. Introduction from LIGO Caltech (2:55).

LIGO’s First Detection of Gravitational Waves: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gw-i_VKd6Wo. Explanation and animations from PBS Digital Studio (9:31).

Two Black Holes Merge into One: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I_88S8DWbcU. Simulation from LIGO Caltech (0:35).

What the Discovery of Gravitational Waves Means: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jMVAgCPYYHY. TED Talk by Allan Adams (10:58).

Collaborative Group Activities

- A computer science major takes an astronomy course like the one you are taking and becomes fascinated with black holes. Later in life, he founds his own internet company and becomes very wealthy when it goes public. He sets up a foundation to support the search for black holes in our Galaxy. Your group is the allocation committee of this foundation. How would you distribute money each year to increase the chances that more black holes will be found?

- Suppose for a minute that stars evolve without losing any mass at any stage of their lives. Your group is given a list of binary star systems. Each binary contains one main-sequence star and one invisible companion. The spectral types of the main-sequence stars range from spectral type O to M. Your job is to determine whether any of the invisible companions might be black holes. Which ones are worth observing? Why? (Hint: Remember that in a binary star system, the two stars form at the same time, but the pace of their evolution depends on the mass of each star.)

- You live in the far future, and the members of your group have been convicted (falsely) of high treason. The method of execution is to send everyone into a black hole, but you get to pick which one. Since you are doomed to die, you would at least like to see what the inside of a black hole is like—even if you can’t tell anyone outside about it. Would you choose a black hole with a mass equal to that of Jupiter or one with a mass equal to that of an entire galaxy? Why? What would happen to you as you approached the event horizon in each case? (Hint: Consider the difference in force on your feet and your head as you cross over the event horizon.)

- General relativity is one of the areas of modern astrophysics where we can clearly see the frontiers of human knowledge. We have begun to learn about black holes and warped spacetime recently and are humbled by how much we still don’t know. Research in this field is supported mostly by grants from government agencies. Have your group discuss what reasons there are for our tax dollars to support such “far out” (seemingly impractical) work. Can you make a list of “far out” areas of research in past centuries that later led to practical applications? What if general relativity does not have many practical applications? Do you think a small part of society’s funds should still go to exploring theories about the nature of space and time?

- Once you all have read this chapter, work with your group to come up with a plot for a science fiction story that uses the properties of black holes.

- Black holes seem to be fascinating not just to astronomers but to the public, and they have become part of popular culture. Searching online, have group members research examples of black holes in music, advertising, cartoons, and the movies, and then make a presentation to share the examples you found with the whole class.

- As mentioned in the Gravity and Time Machines feature box in this chapter, the film Interstellar has a lot of black hole science in its plot and scenery. That’s because astrophysicist Kip Thorne at Caltech had a big hand in writing the initial treatment for the movie, and later producing it. Get your group members together (be sure you have popcorn) for a viewing of the movie and then try to use your knowledge of black holes from this chapter to explain the plot. (Note that the film also uses the concept of a wormhole, which we don’t discuss in this chapter. A wormhole is a theoretically possible way to use a large, spinning black hole to find a way to travel from one place in the universe to another without having to go through regular spacetime to get there.)

Review Questions

How does the equivalence principle lead us to suspect that spacetime might be curved?

If general relativity offers the best description of what happens in the presence of gravity, why do physicists still make use of Newton’s equations in describing gravitational forces on Earth (when building a bridge, for example)?

Einstein’s general theory of relativity made or allowed us to make predictions about the outcome of several experiments that had not yet been carried out at the time the theory was first published. Describe three experiments that verified the predictions of the theory after Einstein proposed it.

If a black hole itself emits no radiation, what evidence do astronomers and physicists today have that the theory of black holes is correct?

What characteristics must a binary star have to be a good candidate for a black hole? Why is each of these characteristics important?

A student becomes so excited by the whole idea of black holes that he decides to jump into one. It has a mass 10 times the mass of our Sun. What is the trip like for him? What is it like for the rest of the class, watching from afar?

What is an event horizon? Does our Sun have an event horizon around it?

What is a gravitational wave and why was it so hard to detect?

What are some strong sources of gravitational waves that astronomers hope to detect in the future?

Suppose the amount of mass in a black hole doubles. Does the event horizon change? If so, how does it change?

Thought Questions

Imagine that you have built a large room around the people in this figure and that this room is falling at exactly the same rate as they are. Galileo showed that if there is no air friction, light and heavy objects that are dropping due to gravity will fall at the same rate. Suppose that this were not true and that instead heavy objects fall faster. Also suppose that the man in the picture is twice as massive as the woman. What would happen? Would this violate the equivalence principle?

A monkey hanging from a tree branch sees a hunter aiming a rifle directly at him. The monkey then sees a flash and knows that the rifle has been fired. Reacting quickly, the monkey lets go of the branch and drops so that the bullet can pass harmlessly over his head. Does this act save the monkey’s life? Why or why not? (Hint: Consider the similarities between this situation and that of the last question.)

Why would we not expect to detect X-rays from a disk of matter about an ordinary star?

Look elsewhere in this book for necessary data, and indicate what the final stage of evolution—white dwarf, neutron star, or black hole—will be for each of these kinds of stars.

- Spectral type-O main-sequence star

- Spectral type-B main-sequence star

- Spectral type-A main-sequence star

- Spectral type-G main-sequence star

- Spectral type-M main-sequence star

Which is likely to be more common in our Galaxy: white dwarfs or black holes? Why?

If the Sun could suddenly collapse to a black hole, how would the period of Earth’s revolution about it differ from what it is now?

You arrange to meet a friend at 5:00 p.m. on Valentine’s Day on the observation deck of the Empire State Building in New York City. You arrive right on time, but your friend is not there. She arrives 5 minutes late and says the reason is that time runs faster at the top of a tall building, so she is on time but you were early. Is your friend right? Does time run slower or faster at the top of a building, as compared with its base? Is this a reasonable excuse for your friend arriving 5 minutes late?

You are standing on a scale in an elevator when the cable snaps, sending the elevator car into free fall. Before the automatic brakes stop your fall, you glance at the scale reading. Does the scale show your real weight? An apparent weight? Something else?

Figuring for Yourself

Look up G, c, and the mass of the Sun in Appendix E and calculate the radius of a black hole that has the same mass as the Sun. (Note that this is only a theoretical calculation. The Sun does not have enough mass to become a black hole.)

Suppose you wanted to know the size of black holes with masses that are larger or smaller than the Sun. You could go through all the steps in Exercise, wrestling with a lot of large numbers with large exponents. You could be clever, however, and evaluate all the constants in the equation once and then simply vary the mass. You could even express the mass in terms of the Sun’s mass and make future calculations really easy. Show that the event horizon equation is equivalent to saying that the radius of the event horizon is equal to 3 km times the mass of the black hole in units of the Sun’s mass.

Use the result from Exercise to calculate the radius of a black hole with a mass equal to: the Earth, a B0-type main-sequence star, a globular cluster, and the Milky Way Galaxy. Look elsewhere in this text and the appendixes for tables that provide data on the mass of these four objects.

Since the force of gravity a significant distance away from the event horizon of a black hole is the same as that of an ordinary object of the same mass, Kepler’s third law is valid. Suppose that Earth collapsed to the size of a golf ball. What would be the period of revolution of the Moon, orbiting at its current distance of 400,000 km? Use Kepler’s third law to calculate the period of revolution of a spacecraft orbiting at a distance of 6000 km.

Glossary

- gravitational wave

- a disturbance in the curvature of spacetime caused by changes in how matter is distributed; gravitational waves propagate at (or near) the speed of light.