59

Theories of Moral Development

The founder of psychoanalysis, Freud (1962), proposed the existence of a tension between the needs of society and the individual. According to Freud, moral development proceeds when the individual’s selfish desires are repressed and replaced by the values of important socializing agents in one’s life (for instance, one’s parents). A proponent of behaviorism, Skinner (1972) similarly focused on socialization as the primary force behind moral development. In contrast to Freud’s notion of a struggle between internal and external forces, Skinner focused on the power of external forces (reinforcement contingencies) to shape an individual’s development. While both Freud and Skinner focused on the external forces that bear on morality (parents in the case of Freud, and behavioral contingencies in the case of Skinner), Piaget (1965) focused on the individual’s construction, construal, and interpretation of morality from a social-cognitive and social-emotional perspective.

Kohlberg (1963) expanded upon Piagetian notions of moral development. While they both viewed moral development as a result of a deliberate attempt to increase the coordination and integration of one’s orientation to the world, Kohlberg provided a systematic 3-level, 6-stage sequence reflecting changes in moral judgment throughout the lifespan. Specifically, Kohlberg argued that development proceeds from a selfish desire to avoid punishment (personal), to a concern for group functioning (societal), to a concern for the consistent application of universal ethical principles (moral).

Turiel (1983) argued for a social domain approach to social cognition, delineating how individuals differentiate moral (fairness, equality, justice), societal (conventions, group functioning, traditions), and psychological (personal, individual prerogative) concepts from early in development throughout the lifespan. Over the past 40 years, research findings have supported this model, demonstrating how children, adolescents, and adults differentiate moral rules from conventional rules, identify the personal domain as a nonregulated domain, and evaluate multifaceted (or complex) situations that involve more than one domain.

For the past 20 years, researchers have expanded the field of moral development, applying moral judgment, reasoning, and emotion attribution to topics such as prejudice, aggression, theory of mind, emotions, empathy, peer relationships, and parent-child interactions.

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development

Kohlberg was interested in moral reasoning. Moral reasoning does not necessarily equate to moral behavior. Holding a particular belief does not mean that our behavior will always be consistent with the belief. To develop this theory, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to people of all ages, and then he analyzed their answers to find evidence of their particular stage of moral development. After presenting people with this and various dilemmas, Kohlberg reviewed people’s responses and placed them in different stages of moral reasoning. According to Kohlberg, an individual progresses from the capacity for pre-conventional morality (before age 9) to the capacity for conventional morality (early adolescence), and toward attaining post-conventional morality (once formal operational thought is attained), which only a few fully achieve.

Moral Stages According to Kohlberg

Using a stage model similar to Piaget’s, Kohlberg proposed three levels, with six stages, of moral development. Individuals experience the stages universally and in sequence as they form beliefs about justice. He named the levels simply preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.

Figure 8.1.1. Kohlberg identified three levels of moral reasoning: pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional: Each level is associated with increasingly complex stages of moral development.

Preconventional: Obedience and Mutual Advantage

The preconventional level of moral development coincides approximately with the preschool period of life and with Piaget’s preoperational period of thinking. At this age, the child is still relatively self-centered and insensitive to the moral effects of actions on others. The result is a somewhat short-sighted orientation to morality. Initially (Kohlberg’s Stage 1), the child adopts an ethics of obedience and punishment —a sort of “morality of keeping out of trouble.” The rightness and wrongness of actions are determined by whether actions are rewarded or punished by authorities, such as parents or teachers. If helping yourself to a cookie brings affectionate smiles from adults, then taking the cookie is considered morally “good.” If it brings scolding instead, then it is morally “bad.” The child does not think about why an action might be praised or scolded; in fact, says Kohlberg, he would be incapable, at Stage 1, of considering the reasons even if adults offered them.

Eventually, the child learns not only to respond to positive consequences but also learns how to produce them by exchanging favors with others. The new ability creates Stage 2, ethics of market exchange. At this stage, the morally “good” action is one that favors not only the child but another person directly involved. A “bad” action is one that lacks this reciprocity. If trading the sandwich from your lunch for the cookies in your friend’s lunch is mutually agreeable, then the trade is morally good; otherwise, it is not. This perspective introduces a type of fairness into the child’s thinking for the first time. However, it still ignores the larger context of actions—the effects on people not present or directly involved. In Stage 2, for example, it would also be considered morally “good” to pay a classmate to do another student’s homework—or even to avoid bullying—provided that both parties regard the arrangement as being fair.

Conventional: Conformity to Peers and Society

As children move into the school years, their lives expand to include a larger number and range of peers and (eventually) of the community as a whole. The change leads to conventional morality, which are beliefs based on what this larger array of people agree on—hence Kohlberg’s use of the term “conventional.” At first, in Stage 3, the child’s reference group are immediate peers, so Stage 3 is sometimes called the ethics of peer opinion. If peers believe, for example, that it is morally good to behave politely with as many people as possible, then the child is likely to agree with the group and to regard politeness as not merely an arbitrary social convention, but a moral “good.” This approach to moral belief is a bit more stable than the approach in Stage 2 because the child is taking into account the reactions not just of one other person, but of many. But it can still lead astray if the group settles on beliefs that adults consider morally wrong, like “Shoplifting for candy bars is fun and desirable.”

Eventually, as the child becomes a youth and the social world expands, even more, he or she acquires even larger numbers of peers and friends. He or she is, therefore, more likely to encounter disagreements about ethical issues and beliefs. Resolving the complexities lead to Stage 4, the ethics of law and order, in which the young person increasingly frames moral beliefs in terms of what the majority of society believes. Now, an action is morally good if it is legal or at least customarily approved by most people, including people whom the youth does not know personally. This attitude leads to an even more stable set of principles than in the previous stage, though it is still not immune from ethical mistakes. A community or society may agree, for example, that people of a certain race should be treated with deliberate disrespect, or that a factory owner is entitled to dump wastewater into a commonly shared lake or river. To develop ethical principles that reliably avoid mistakes like these require further stages of moral development.

Postconventional: Social Contract and Universal Principles

As a person becomes able to think abstractly (or “formally,” in Piaget’s sense), ethical beliefs shift from acceptance of what the community does believe to the process by which community beliefs are formed. The new focus constitutes Stage 5, the ethics of social contract. Now an action, belief, or practice is morally good if it has been created through fair, democratic processes that respect the rights of the people affected. Consider, for example, the laws in some areas that require motorcyclists to wear helmets. In what sense are the laws about this behavior ethical? Was it created by consulting with and gaining the consent of the relevant people? Were cyclists consulted, and did they give consent? Or how about doctors or the cyclists’ families? Reasonable, thoughtful individuals disagree about how thoroughly and fairly these consultation processes should be. In focusing on the processes by which the law was created; however, individuals are thinking according to Stage 5, the ethics of social contract, regardless of the position they take about wearing helmets. In this sense, beliefs on both sides of a debate about an issue can sometimes be morally sound, even if they contradict each other.

Paying attention to due process certainly seems like it should help to avoid mindless conformity to conventional moral beliefs. As an ethical strategy, though, it too can sometimes fail. The problem is that an ethics of social contract places more faith in the democratic process than the process sometimes deserves, and does not pay enough attention to the content of what gets decided. In principle (and occasionally in practice), a society could decide democratically to kill off every member of a racial minority, but would deciding this by due process make it ethical? The realization that ethical means can sometimes serve unethical ends leads some individuals toward Stage 6, the ethics of self-chosen, universal principles. At this final stage, the morally good action is based on personally held principles that apply both to the person’s immediate life as well as to the larger community and society. The universal principles may include a belief in democratic due process (Stage 5 ethics), but also other principles, such as a belief in the dignity of all human life or the sacredness of the natural environment. At Stage 6, the universal principles will guide a person’s beliefs even if the principles mean occasionally disagreeing with what is customary (Stage 4) or even with what is legal (Stage 5).

Video 8.1.1. Kohlberg’s Six Stages of Moral Development explains the stages of moral reasoning and applies it to an example scenario.

Kohlberg and the Heinz Dilemma

The Heinz dilemma is a frequently used example to help us understand Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. How would you answer this dilemma? Kohlberg was not interested in whether you answer yes or no to the dilemma: Instead, he was interested in the reasoning behind your answer.

In Europe, a woman was near death from a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that the doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to make. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1,000, which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said: “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So Heinz got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that? (Kohlberg, 1969, p. 379)

From a theoretical point of view, it is not important what the participant thinks that Heinz should do. Kohlberg’s theory holds that the justification the participant offers is what is significant, the form of their response. Below are some of many examples of possible arguments that belong to the six stages:

- Stage one (obedience): Heinz should not steal the medicine because he will consequently be put in prison, which will mean he is a bad person. OR Heinz should steal the medicine because it is only worth $200 and not how much the druggist wanted for it; Heinz had even offered to pay for it and was not stealing anything else.

- Stage two (self-interest): Heinz should steal the medicine because he will be much happier if he saves his wife, even if he will have to serve a prison sentence. OR Heinz should not steal the medicine because prison is an awful place, and he would more likely languish in a jail cell than over his wife’s death.

- Stage three (conformity): Heinz should steal the medicine because his wife expects it; he wants to be a good husband. OR Heinz should not steal the drug because stealing is bad, and he is not a criminal; he has tried to do everything he can without breaking the law, you cannot blame him.

- Stage four (law-and-order): Heinz should not steal the medicine because the law prohibits stealing, making it illegal. OR Heinz should steal the drug for his wife but also take the prescribed punishment for the crime as well as paying the druggist what he is owed. Criminals cannot just run around without regard for the law; actions have consequences.

- Stage five (social contract orientation): Heinz should steal the medicine because everyone has a right to choose life, regardless of the law. OR Heinz should not steal the medicine because the scientist has a right to fair compensation. Even if his wife is sick, it does not make his actions right.

- Stage six (universal human ethics): Heinz should steal the medicine because saving a human life is a more fundamental value than the property rights of another person. OR Heinz should not steal the medicine because others may need medicine just as badly.

Evaluating the Kohlberg’s idea

Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment and social rules and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. For one, people may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that the stage model is particularly appropriate for Western, rather than non-Western, samples in which allegiance to social norms, such as respect for authority, may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). In addition, there is frequently little correlation between how we score on the moral stages and how we behave in real life.

Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it may describe the moral development of males better than it describes that of females (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000). One of Kohlberg’s students, Carol Gilligan (1982) has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. Although there is little evidence for a gender difference in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), it is true that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000).[1]

Carol Gilligan and the Morality of Care

Carol Gilligan [2]

As logical as they sound, Kohlberg’s stages of moral justice are not sufficient for understanding the development of moral beliefs. To see why this is, suppose that you have a student who asks for an extension of the deadline for an assignment. The justice orientation of Kohlberg’s theory would prompt you to consider issues of whether granting the request is fair. Would the late student be able to put more effort into the assignment than other students? Would the extension place a difficult demand on you since you would have less time to mark the assignments? These are important considerations related to the rights of students and the teacher. In addition to these, however, are considerations having to do with the responsibilities that you and the requesting student have for each other and for others. Does the student have a valid personal reason (illness, death in the family, etc.) for the assignment being late? Will the assignment lose its educational value if the student has to turn it in prematurely? These latter questions have less to do with fairness and rights, and more to do with taking care of and responsibility for students. They require a framework different from Kohlberg’s to be understood fully.

One such framework has been developed by Carol Gilligan, whose ideas center on the morality of care, or a system of beliefs about human responsibilities, care, and consideration for others. Gilligan proposed three moral positions that represent different extents or breadth of ethical care. Unlike Kohlberg, Piaget, or Erikson, she does not claim that the positions form a strictly developmental sequence, but only that they can be ranked hierarchically according to their depth or subtlety. In this respect, her theory is “semi-developmental” in a way similar to Maslow’s theory of motivation (Brown & Gilligan, 1992; Taylor, Gilligan, & Sullivan, 1995). The table below summarizes the three moral positions from Gilligan’s theory:

Positions of Moral Development According to Gilligan

Table 8.1.1. Gilligan’s three moral positions

| Moral Position | Definition of What is Morally Good |

| Position 1: Survival orientation | Action that considers one’s personal needs only |

| Position 2: Conventional care | Action that considers others’ needs or preferences, but not one’s own |

| Position 3: Integrated care | Action that attempts to coordinate one’s own personal needs with those of others. |

Position 1: Survival Orientation

The most basic kind of caring is a survival orientation, in which a person is concerned primarily with his or her own welfare. If a teenage girl with this ethical position is wondering whether to get an abortion, for example, she will be concerned entirely with the effects of the abortion on herself. The morally good choice will be whatever creates the least stress for herself and that disrupts her own life the least. Responsibilities to others (the baby, the father, or her family) play little or no part in her thinking.

As a moral position, a survival orientation is obviously not satisfactory for classrooms on a widespread scale. If every student only looked out for himself or herself, classroom life might become rather unpleasant! Nonetheless, there are situations in which focusing primarily on yourself is both a sign of good mental health and relevant to teachers. For a child who has been bullied at school or sexually abused at home, for example, it is both healthy and morally desirable to speak out about how bullying or abuse has affected the victim. Doing so means essentially looking out for the victim’s own needs at the expense of others’ needs, including the bully’s or abuser’s. Speaking out, in this case, requires a survival orientation and is healthy because the child is taking care of themself.

Position 2: Conventional Caring

A more subtle moral position is conventional caring (caring for others), in which a person is concerned about others’ happiness and welfare, and about reconciling or integrating others’ needs where they conflict with each other. In considering an abortion, for example, the teenager at this position would think primarily about what other people prefer. Do the father, her parents, and/or her doctor want her to keep the child? The morally good choice becomes whatever will please others the best. This position is more demanding than Position 1, ethically and intellectually, because it requires coordinating several persons’ needs and values. But it is often morally insufficient because it ignores one crucial person: the self.

In classrooms, students who operate from Position 2 can be very desirable in some ways; they can be eager to please, considerate, and good at fitting in and at working cooperatively with others. Because these qualities are usually welcome in a busy classroom, teachers can be tempted to reward students for developing and using them. The problem with rewarding Position 2 ethics, however, is that doing so neglects the student’s development—his or her own academic and personal goals or values. Sooner or later, personal goals, values, and identity need attention and care, and educators have a responsibility for assisting students to discover and clarify them.

Position 3: Integrated Caring

The most developed form of moral caring in Gilligan’s model is integrated caring, the coordination of personal needs and values with those of others. Now the morally good choice takes account of everyone including yourself, not everyone except yourself. In considering an abortion, a woman at Position 3 would think not only about the consequences for the father, the unborn child, and her family but also about the consequences for herself. How would bearing a child affect her own needs, values, and plans? This perspective leads to moral beliefs that are more comprehensive but ironically are also more prone to dilemmas because the widest possible range of individuals are being considered.

In classrooms, integrated caring is most likely to surface whenever teachers give students wide, sustained freedom to make choices. If students have little flexibility about their actions, there is little room for considering anyone’s needs or values, whether their own or others. If the teacher says simply: “Do the homework on page 50 and turn it in tomorrow morning,” then the main issue becomes compliance, not a moral choice. But suppose instead that she says something like this: “Over the next two months, figure out an inquiry project about the use of water resources in our town. Organize it any way you want—talk to people, read widely about it, and share it with the class in a way that all of us, including yourself, will find meaningful.” An assignment like this poses moral challenges that are not only educational but also moral since it requires students to make value judgments. Why? For one thing, students must decide what aspect of the topic really matters to them. Such a decision is partly a matter of personal values. For another thing, students have to consider how to make the topic meaningful or important to others in the class. Third, because the timeline for completion is relatively far in the future, students may have to weigh personal priorities (like spending time with friends or family) against educational priorities (working on the assignment a bit more on the weekend). As you might suspect, some students might have trouble making good choices when given this sort of freedom—and their teachers might therefore be cautious about giving such an assignment. But the difficulties in making choices are part of Gilligan’s point: integrated caring is indeed more demanding than caring based only on survival or on consideration of others. Not all students may be ready for it.[3]

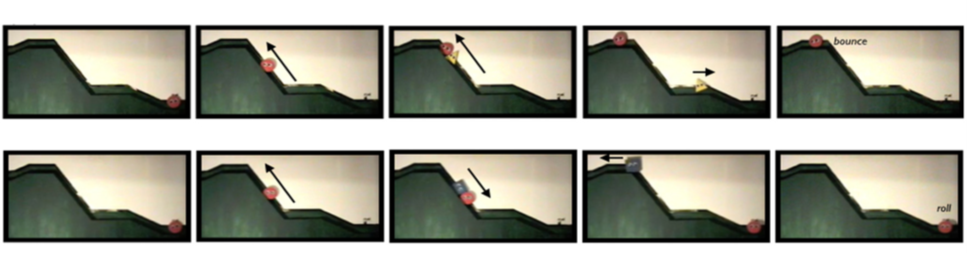

Are We Born Moral? Helpers and Hinderers

In a 2007 Hamlin, Wynn, and Bloom provided the first evidence that preverbal infants at 6 and at 10 months of age evaluate others on the basis of their helpful and unhelpful actions toward unknown third parties using what they called a “hill paradigm.” All events began with a “Climber” (most commonly a red, circular wooden character with large plastic ‘googly’ eyes) resting at the bottom of a hill containing two inclines, one shallow and one steep. To imply that the Climber’s goal was to reach the top of the hill, the googly portions of the Climber’s eyes were fixed diagonally upward such that he “gazed” uphill during the entirety of each event. “Helpers” and “Hinderers” were most commonly a blue square and a yellow triangle (whose googly eyes remained moveable); whether the square or the triangle was the Helper was counterbalanced

across infants.

At the start of both Helper and Hinderer events, the Climber first moved easily up the shallow incline to a landing where he wiggled back and forth. He then made two unsuccessful attempts to climb the steeper incline; on his first attempt he made it 1/3 of the way up before coming back down and on his second attempt he made it 2/3 of the way. To imply the Climber’s movements up and down the hill reflected a failed intention to climb to the top, during each ascent the Climber decelerated as though fighting upward against gravity, while during each descent he accelerated as though falling down with gravity. On the Climber’s third attempt, Helper and Hinderer events diverged. During Helper events, the Helper entered the scene from the bottom of the hill and bumped the Climber up from below twice, pushing him to the top of the steep incline. The Climber then bounced up and down for several seconds (as though happy to have achieved his goal) and the Helper moved back down the hill and offstage. During Hinderer events, the Hinderer entered the scene from the top of the hill and bumped the Climber down from above twice, forcing him to the bottom of the steep incline. The Climber then rolled end-over-end to the very bottom of the hill and the Hinderer moved back up the hill and offstage. Infants viewed alternating Helper and Hinderer events until a pre-set habituation criterion was reached. Following habituation, infants were presented with soft, stuffed, doll images of the the Helper and Hinderer to reach for. Both 6- and 10-month-olds selectively reached for the Helper, leading Hamlin, Wynn, and Bloom (2007) to conclude that the infants had based their decisions on a preference for those who performed positive social acts over those who performed negative social acts, and that this preference formed the basis for the development of later moral cognition [4]

Think It Over

Consider your decision-making processes. What guides your decisions? Are you primarily concerned with your personal well-being? Do you make choices based on what other people will think about your decision? Or are you guided by other principles? To what extent is this approach guided by your culture?

Media Attributions

- Private: Chapter 11 Helpers and Hinderers Number 2

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Image was retrieved from wikiwand.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Educational Psychology by Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . However, the link for the text is broken. The text with citation can be found at OER Services ↵

- from Hamlin, J.K. (2015) Front. Psychol., 29 January 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01563 is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵