39 Information Processing: Organization of Thinking and Metacognition

Organization of Thinking

During middle childhood and adolescence, young people can learn and remember more due to improvements in the way they attend to and store information. As people learn more about the world, they develop more categories for concepts and learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information. One significant reason is that they continue to have more experiences on which to tie new information. In other words, their knowledge base, knowledge in particular areas that makes learning new information easier, expands (Berger, 2014).

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

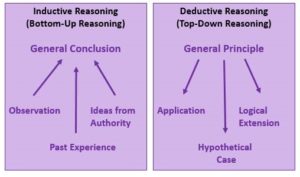

Inductive reasoning emerges in childhood and is a type of reasoning that is sometimes characterized as “bottom-up- processing” in which specific observations, or specific comments from those in authority, may be used to draw general conclusions. However, in inductive reasoning, the veracity of the information that created the general conclusion does not guarantee the accuracy of that conclusion. For instance, a child who has only observed thunder on summer days may conclude that it only thunders in the summer. In contrast, deductive reasoning, sometimes called “top-down-processing,” emerges in adolescence. This type of reasoning starts with some overarching principle and, based on this, propose specific conclusions. Deductive reasoning guarantees an accurate conclusion if the premises on which it is based are accurate.

Figure 5.7.1. Models of inductive and deductive reasoning.

Intuitive versus Analytic Thinking

Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the Dual-Process Model, the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast (Kahneman, 2011), and it is more experiential and emotional. In contrast, Analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational. While these systems interact, they are distinct (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier and more commonly used in everyday life. It is also more commonly used by children and teens than by adults (Klaczynski, 2001). The quickness of adolescent thought, along with the maturation of the limbic system, may make teens more prone to emotional, intuitive thinking than adults.

Critical Thinking

There is a debate in U.S. education as to whether schools should teach students what to think or how to think. Critical thinking, or a detailed examination of beliefs, courses of action, and evidence, involves teaching children how to think. The purpose of critical thinking is to evaluate information in ways that help us make informed decisions. Critical thinking involves better understanding a problem through gathering, evaluating, and selecting information, and also by considering many possible solutions. Ennis (1987) identified several skills useful in critical thinking. These include: Analyzing arguments, clarifying information, judging the credibility of a source, making value judgments, and deciding on an action. Metacognition is essential to critical thinking because it allows us to reflect on the information as we make decisions.

Metacognition

As children mature through middle and late childhood and into adolescence, they have a better understanding of how well they are performing a task and the level of difficulty of a task. As they become more realistic about their abilities, they can adapt studying strategies to meet those needs. Young children spend as much time on an unimportant aspect of a problem as they do on the main point, while older children start to learn to prioritize and gauge what is significant and what is not. As a result, they develop metacognition. Metacognition refers to the knowledge we have about our thinking and our ability to use this awareness to regulate our cognitive processes.

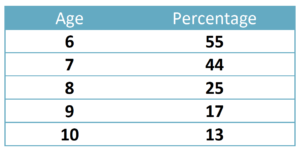

Bjorklund (2005) describes a developmental progression in the acquisition and use of memory strategies. Such strategies are often lacking in younger children but increase in frequency as children progress through elementary school. Examples of memory strategies include rehearsing information you wish to recall, visualizing and organizing information, creating rhymes, such as “i” before “e” except after “c,” or inventing acronyms, such as “ROYGBIV” to remember the colors of the rainbow. Schneider, Kron-Sperl, and hünnerkopf (2009) reported a steady increase in the use of memory strategies from ages six to ten in their longitudinal study (see table 5.7.1). Moreover, by age ten, many children were using two or more memory strategies to help them recall information. Schneider and colleagues found that there were considerable individual differences at each age in the use of strategies and that children who utilized more strategies had better memory performance than their same-aged peers.

Table 5.7.1. Percentage of children who did not use any memory strategies by age.

A person may experience three deficiencies in their use of memory strategies. A mediation deficiency occurs when a person does not grasp the strategy being taught, and thus, does not benefit from its use. If you do not understand why using an acronym might be helpful, or how to create an acronym, the strategy is not likely to help you. In a production deficiency, the person does not spontaneously use a memory strategy and has to be prompted to do so. In this case, the person knows the strategy and is more than capable of using it, but they fail to “produce” the strategy on their own. For example, a child might know how to make a list but may fail to do this to help them remember what to bring on a family vacation. A utilization deficiency refers to a person using an appropriate strategy, but it fails to aid their performance. Utilization deficiency is common in the early stages of learning a new memory strategy. Until the use of the strategy becomes automatic, it may slow down the learning process, as space is taken up in memory by the strategy itself. Initially, children may get frustrated because their memory performance may seem worse when they try to use the new strategy. Once children become more adept at using the strategy, their memory performance will improve. Sodian and Schneider (1999) found that new memory strategies acquired before age 8 often show utilization deficiencies, with there being a gradual improvement in the child’s use of the strategy. In contrast, strategies acquired after this age often followed an “all-or-nothing” principle in which improvement was not gradual, but abrupt.