38 Information Processing: Executive Function

Executive Functions

Changes in our information processing skills also involved changes in executive function. Executive function is generally understood to include three core components: working memory, shifting (also called cognitive flexibility), and inhibition. These components develop significantly during childhood and adolescence and are critical for academic, social, and emotional functioning.

Working Memory

As discussed earlier, working memory refers to the ability to temporarily hold and manipulate information in your mind. For example, if you’re asked to solve 13 + 25 mentally, you might break the task into steps like this:

-

10 + 20 = 30

-

3 + 5 = 8

-

30 + 8 = 38

To arrive at the correct answer, you need to store intermediate results (30 and 8) while still actively processing the remaining steps. This illustrates how working memory allows us to hold onto partial information while performing mental operations.

Working memory is essential for nearly all everyday activities—from cooking and following instructions to reading comprehension and problem-solving. In the classroom, strong working memory supports learning across subjects, and children with higher working memory capacity often perform better academically.

Shifting

Shifting, or cognitive flexibility, refers to the ability to adapt your thinking and switch between different tasks, rules, or mental sets. For instance, moving from solving a math problem to reading a story requires a mental shift in focus and strategy.

Shifting is especially important in school settings, where students must frequently transition between subjects and activities. Even outside of academics, shifting is needed to navigate daily routines—for example, transitioning from a structured classroom environment to the more relaxed mindset of being at home. Strong shifting ability allows individuals to adapt more easily to changing situations and demands.

Inhibition

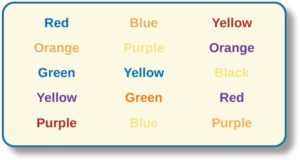

Inhibition is the ability to suppress automatic, impulsive, or irrelevant responses in favor of goal-directed behavior. A classic example is the Stroop task, where you’re shown color words (e.g., the word “red” written in blue ink) and asked to name the ink color rather than reading the word. Doing so requires you to inhibit the automatic tendency to read the word and instead focus your attention on the color.

Figure 5.6.1. The Stroop effect is a task that requires inhibition

Inhibition is key to self-control and attention regulation. It helps children wait their turn, resist distractions, and follow rules—all of which are critical for successful learning and social interactions.

Development of Executive Function

These core components of executive function—working memory, shifting, and inhibition—begin to emerge in early childhood and continue to develop throughout childhood and adolescence. Like many other cognitive abilities, the development of executive function is shaped by both brain maturation—particularly in the prefrontal cortex—and environmental experiences. Research has shown that children raised in cognitively stimulating environments, with warm and responsive caregivers who use strategies such as scaffolding during problem-solving tasks, tend to develop stronger executive function skills (Fay-Stammbach, Hawes, & Meredith, 2014). For example, scaffolding behaviors have been found to be positively associated with cognitive flexibility at age two and inhibitory control at age four (Bibok, Carpendale, & Müller, 2009). These findings highlight the importance of both biological and social influences in supporting the development of self-regulation and higher-order thinking skills.