53 Self Efficacy Development in Middle Childhood and Adolescence

Self-Efficacy

Imagine two students, Sally and Lucy, who are about to take the same math test. Sally and Lucy have the same exact ability to do well in math, the same level of intelligence, and the same motivation to do well on the test. They also studied together. They even have the same brand of shoes on. The only difference between the two is that Sally is very confident in her mathematical and her test-taking abilities, while Lucy is not. So, who is likely to do better on the test? Sally, of course, because she has the confidence to use her mathematical and test-taking abilities to deal with challenging math problems and to accomplish goals that are important to her—in this case, doing well on the test. This difference between Sally and Lucy—the student who got the A and the student who got the B-, respectively—is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy influences behavior and emotions in particular ways that help people better manage challenges and achieve valued goals.

A concept that was first introduced by Albert Bandura in 1977, self-efficacy refers to a person’s belief that he or she is able to effectively perform the tasks needed to attain a valued goal (Bandura, 1977). Since then, self-efficacy has become one of the most thoroughly researched concepts in psychology. Just about every important domain of human behavior has been investigated using self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1977; Maddux, 1995). Self-efficacy does not refer to your abilities but rather to your beliefs about what you can do with your abilities. Also, self-efficacy is not a trait—there are not certain types of people with high self-efficacies and others with low self-efficacies (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Rather, people have self-efficacy beliefs about specific goals and life domains. For example, if you believe that you have the skills necessary to do well in school and believe you can use those skills to excel, then you have high academic self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy may sound similar to a concept you may be familiar with already—self-esteem—but these are very different notions. Self-esteem refers to how much you like or “esteem” yourself—to what extent you believe you are a good and worthwhile person. Self-efficacy, however, refers to your self-confidence to perform well and to achieve in specific areas of life such as school, work, and relationships. Self-efficacy does influence self-esteem because how you feel about yourself overall is greatly influenced by your confidence in your ability to perform well in areas that are important to you and to achieve valued goals. For example, if performing well in athletics is very important to you, then your self-efficacy for athletics will greatly influence your self-esteem; however, if performing well in athletics is not at all important to you, then your self-efficacy for athletics will probably have little impact on your self-esteem.

Self-efficacy begins to develop in very young children. Once self-efficacy is developed, it does not remain constant—it can change and grow as an individual has different experiences throughout his or her lifetime. When children are very young, their parents’ self-efficacies are important (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Children of parents who have high parental self-efficacies perceive their parents as more responsive to their needs (Gondoli & Silverberg, 1997). Around the ages of 12 through 16, adolescents’ friends also become an important source of self-efficacy beliefs. Adolescents who associate with peer groups that are not academically motivated tend to experience a decline in academic self-efficacy (Wentzel, Barry, & Caldwell, 2004). Adolescents who watch their peers succeed, however, experience a rise in academic self-efficacy (Schunk & Miller, 2002). This is an example of gaining self-efficacy through vicarious performances, as discussed above. The effects of self-efficacy that develop in adolescence are long-lasting. One study found that greater social and academic self-efficacy measured in people ages 14 to 18 predicted greater life satisfaction five years later (Vecchio, Gerbino, Pastorelli, Del Bove, & Caprara, 2007).

Video 7.5.1. Self-Esteem, Self-Efficacy, and Locus of Control.

Major Influences on Self-Efficacy

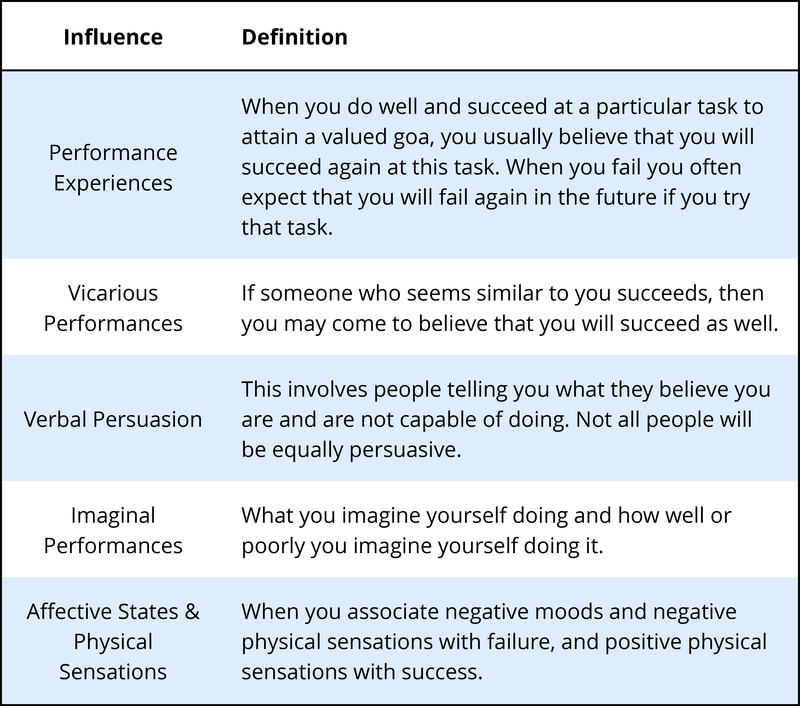

Self-efficacy beliefs are influenced in five different ways (Bandura, 1997), which are summarized in the table below.

These five types of self-efficacy influence can take many real-world forms that almost everyone has experienced. You may have had previous performance experiences affect your academic self-efficacy when you did well on a test and believed that you would do well on the next test. A vicarious performance may have affected your athletic self-efficacy when you saw your best friend skateboard for the first time and thought that you could skateboard well, too. Verbal persuasion could have affected your academic self-efficacy when a teacher that you respect told you that you could get into the college of your choice if you studied hard for the SATs. It’s important to know that not all people are equally likely to influence your self-efficacy though verbal persuasion. People who appear trustworthy or attractive, or who seem to be experts, are more likely to influence your self-efficacy than are people who do not possess these qualities (Petty & Brinol, 2010). That’s why a teacher you respect is more likely to influence your self-efficacy than a teacher you do not respect. Imaginal performances are an effective way to increase your self-efficacy. For example, imagining yourself doing well on a job interview actually leads to more effective interviewing (Knudstrup, Segrest, & Hurley, 2003). Affective states and physical sensations abound when you think about the times you have given presentations in class. For example, you may have felt your heart racing while giving a presentation. If you believe your heart was racing because you had just had a lot of caffeine, it likely would not affect your performance. If you believe your heart was racing because you were doing a poor job, you might believe that you cannot give the presentation well. This is because you associate the feeling of anxiety with failure and expect to fail when you are feeling anxious.

Benefits of High Self-Efficacy

Academic Performance

Consider academic self-efficacy in your own life and recall the earlier example of Sally and Lucy. Are you more like Sally, who has high academic self-efficacy and believes that she can use her abilities to do well in school, or are you more like Lucy, who does not believe that she can effectively use her academic abilities to excel in school? Do you think your own self-efficacy has ever affected your academic ability? Do you think you have ever studied more or less intensely because you did or did not believe in your abilities to do well? Many researchers have considered how self-efficacy works in academic settings, and the short answer is that academic self-efficacy affects every possible area of academic achievement (Pajares, 1996).

Students who believe in their ability to do well academically tend to be more motivated in school (Schunk, 1991). When self-efficacious students attain their goals, they continue to set even more challenging goals (Schunk, 1990). This can all lead to better performance in school in terms of higher grades and taking more challenging classes (Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991). For example, students with high academic self-efficacies might study harder because they believe that they are able to use their abilities to study effectively. Because they studied hard, they receive an A on their next test. Teachers’ self-efficacies also can affect how well a student performs in school. Self-efficacious teachers encourage parents to take a more active role in their children’s learning, leading to better academic performance (Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler, & Brissie, 1987).

Although there is a lot of research about how self-efficacy is beneficial to school-aged children, college students can also benefit from self-efficacy. Freshmen with higher self-efficacies about their ability to do well in college tend to adapt to their first year in college better than those with lower self-efficacies (Chemers, Hu, & Garcia, 2001). The benefits of self-efficacy continue beyond the school years: people with strong self-efficacy beliefs toward performing well in school tend to perceive a wider range of career options (Lent, Brown, & Larkin, 1986). In addition, people who have stronger beliefs of self-efficacy toward their professional work tend to have more successful careers (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998).

One question you might have about self-efficacy and academic performance is how a student’s actual academic ability interacts with self-efficacy to influence academic performance. The answer is that a student’s actual ability does play a role, but it is also influenced by self-efficacy. Students with greater ability perform better than those with lesser ability. But, among a group of students with the same exact level of academic ability, those with stronger academic self-efficacies outperform those with weaker self-efficacies. One study (Collins, 1984) compared performance on difficult math problems among groups of students with different levels of math ability and different levels of math self-efficacy. Among a group of students with average levels of math ability, the students with weak math self-efficacies got about 25% of the math problems correct. The students with average levels of math ability and strong math self-efficacies got about 45% of the questions correct. This means that by just having stronger math self-efficacy, a student of average math ability will perform 20% better than a student with similar math ability but weaker math self-efficacy. You might also wonder if self-efficacy makes a difference only for people with average or below-average abilities. Self-efficacy is important even for above-average students. In this study, those with above-average math abilities and low math self-efficacies answered only about 65% of the questions correctly; those with above-average math abilities and high math self-efficacies answered about 75% of the questions correctly.

Healthy Behaviors

Think about a time when you tried to improve your health, whether through dieting, exercising, sleeping more, or any other way. Would you be more likely to follow through on these plans if you believed that you could effectively use your skills to accomplish your health goals? Many researchers agree that people with stronger self-efficacies for doing healthy things (e.g., exercise self-efficacy, dieting self-efficacy) engage in more behaviors that prevent health problems and improve overall health (Strecher, DeVellis, Becker, & Rosenstock, 1986). People who have strong self-efficacy beliefs about quitting smoking are able to quit smoking more easily (DiClemente, Prochaska, & Gibertini, 1985). People who have strong self-efficacy beliefs about being able to reduce their alcohol consumption are more successful when treated for drinking problems (Maisto, Connors, & Zywiak, 2000). People who have stronger self-efficacy beliefs about their ability to recover from heart attacks do so more quickly than those who do not have such beliefs (Ewart, Taylor, Reese, & DeBusk, 1983).

One group of researchers (Roach Yadrick, Johnson, Boudreaux, Forsythe, & Billon, 2003) conducted an experiment with people trying to lose weight. All people in the study participated in a weight loss program that was designed for the U.S. Air Force. This program had already been found to be very effective, but the researchers wanted to know if increasing people’s self-efficacies could make the program even more effective. So, they divided the participants into two groups: one group received an intervention that was designed to increase weight loss self-efficacy along with the diet program, and the other group received only the diet program. The researchers tried several different ways to increase self-efficacy, such as having participants read a copy of Oh, The Places You’ll Go! by Dr. Seuss (1990), and having them talk to someone who had successfully lost weight. The people who received the diet program and an intervention to increase self-efficacy lost an average of 8.2 pounds over the 12 weeks of the study; those participants who had only the diet program lost only 5.8 pounds. Thus, just by increasing weight loss self-efficacy, participants were able to lose over 50% more weight.

Studies have found that increasing a person’s nutritional self-efficacy can lead them to eat more fruits and vegetables (Luszczynska, Tryburcy, & Schwarzer, 2006). Self-efficacy plays a large role in successful physical exercise (Maddux & Dawson, 2014). People with stronger self-efficacies for exercising are more likely to plan on beginning an exercise program, actually beginning that program (DuCharme & Brawley, 1995), and continuing it (Marcus, Selby, Niaura, & Rossi, 1992). Self-efficacy is especially important when it comes to safe sex. People with greater self-efficacies about condom usage are more likely to engage in safe sex (Kaneko, 2007), making them more likely to avoid sexually transmitted diseases, such as HIV (Forsyth & Carey, 1998).

Athletic Performance

If you are an athlete, self-efficacy is especially important in your life. Professional and amateur athletes with stronger self-efficacy beliefs about their athletic abilities perform better than athletes with weaker levels of self-efficacy (Wurtele, 1986). This holds true for athletes in all types of sports, including track and field (Gernigon & Delloye, 2003), tennis (Sheldon & Eccles, 2005), and golf (Bruton, Mellalieu, Shearer, Roderique-Davies, & Hall, 2013). One group of researchers found that basketball players with strong athletic self-efficacy beliefs hit more foul shots than did basketball players with weak self-efficacy beliefs (Haney & Long, 1995). These researchers also found that the players who hit more foul shots had greater increases in self-efficacy after they hit the foul shots compared to those who hit fewer foul shots and did not experience increases in self-efficacy. This is an example of how we gain self-efficacy through performance experiences.