3

What is a Theory?

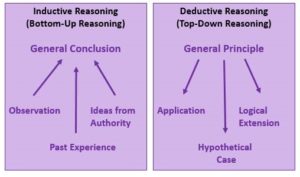

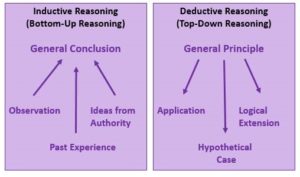

Theories are simply an explanation of something and can be valuable tools for understanding human behavior. In fact, developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development. Theory is usually the first step of conducting research. Theories help guide and interpret research findings by providing researchers with help putting together various research findings. Think of theories as a story that is used to both explain behaviors and to guide research. Each time a researcher conducts an experiment to test the validity of a theory another page is being added to the story. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

Historical Theories of Development

Today, children are widely seen as vulnerable individuals who need protection and care. Child labor is considered unacceptable, and society generally believes that children should be nurtured. However, this view has changed over time. Historically, children were viewed as “little adults”—they wore miniature versions of adult clothing and were expected to take on adult responsibilities. Their developing bodies and limited strength were not seen as reasons for extra care but rather as flaws. This perspective began to shift in the 18th century, as people started to recognize childhood as a distinct and important stage of development.

John Locke (1632-1704) [1]

John Locke, a British philosopher, refuted the idea of innate knowledge and instead proposed that children are largely shaped by their social environments, especially their education as adults teach them important knowledge. He believed that through education a child learns socialization, or what is needed to be an appropriate member of society. Locke advocated thinking of a child’s mind as a tabula rasa or blank slate, and whatever comes into the child’s mind comes from the environment. Locke emphasized that the environment is especially powerful in the child’s early life because he considered the mind the most pliable then. Locke indicated that the environment exerts its effects through associations between thoughts and feelings, behavioral repetition, imitation, and rewards and punishments (Crain, 2005). Locke’s ideas laid the groundwork for the behavioral perspective and subsequent learning theories of Pavlov, Skinner and Bandura.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) [2]

Like Locke, Rousseau also believed that children were not just little adults. However, he did not believe they were blank slates, but instead developed according to a natural plan which unfolded in different stages (Crain, 2005). He did not believe in teaching them the correct way to think but believed children should be allowed to think by themselves according to their own ways and an inner, biological timetable. This focus on biological maturation resulted in Rousseau being considered the father of developmental psychology. Followers of Rousseau’s developmental perspective include Gesell, Montessori, and Piaget.

Contemporary Theories of Development

Psychoanalytic Theories

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and Psychoanalytic Theory [3]

While sometimes controversial, Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resiliency in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

While sometimes controversial, Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resiliency in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

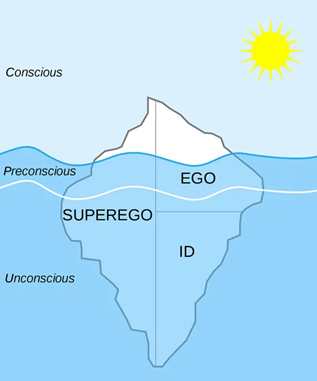

Freud’s Theory of the Mind

Freud believed that most of our mental processes, motivations and desires are outside of our awareness. Our consciousness, that of which we are aware, represents only the tip of the iceberg that comprises our mental state. The preconscious represents that which can easily be called into the conscious mind. During development, our motivations and desires are gradually pushed into the unconscious because raw desires are often unacceptable in society.

Freud’s Theory of the Self

As adults, our personality or self consists of three main parts: the id, the ego and the superego. The id is the part of the self with which we are born. It consists of the biologically driven self and includes our instincts and drives. It is the part of us that wants immediate gratification. Later in life, it comes to house our deepest, often unacceptable desires such as sex and aggression. It operates under the pleasure principle which means that the criteria for determining whether something is good or bad is whether it feels good or bad. An infant is all id. The ego is the part of the self that develops as we learn that there are limits on what is acceptable to do and that often, we must wait to have our needs satisfied. This part of the self is realistic and reasonable. It knows how to make compromises. It operates under the reality principle or the recognition that sometimes need gratification must be postponed for practical reasons. It acts as a mediator between the id and the superego and is viewed as the healthiest part of the self.[4]

The superego’s function is to control the id’s impulses, especially those which society forbids, such as sex and aggression. It also has the function of persuading the ego to turn to moralistic goals rather than simply realistic ones and to strive for perfection.

The superego consists of two systems: The conscience and the ideal self. The conscience can punish the ego through causing feelings of guilt. For example, if the ego gives in to the id’s demands, the superego may make the person feel bad through guilt.

The ideal self (or ego-ideal) is an imaginary picture of how you ought to be, and represents career aspirations, how to treat other people, and how to behave as a member of society.

Behavior which falls short of the ideal self may be punished by the superego through guilt. The super-ego can also reward us through the ideal self when we behave ‘properly’ by making us feel proud. If a person’s ideal self is too high a standard, then whatever the person does will represent failure. The ideal self and conscience are largely determined in childhood from parental values and how you were brought up.[5]

Freud’s Levels of Consciousness in Relation to the Id, Ego, and Superego

Freud’s description of personality shows that the ego operates primarily at the conscious level, but also operates somewhat at both the preconscious and unconscious level as does the superego. However, the superego operates mostly at the unconscious level whereas the id totally functions at the unconscious level. [6]

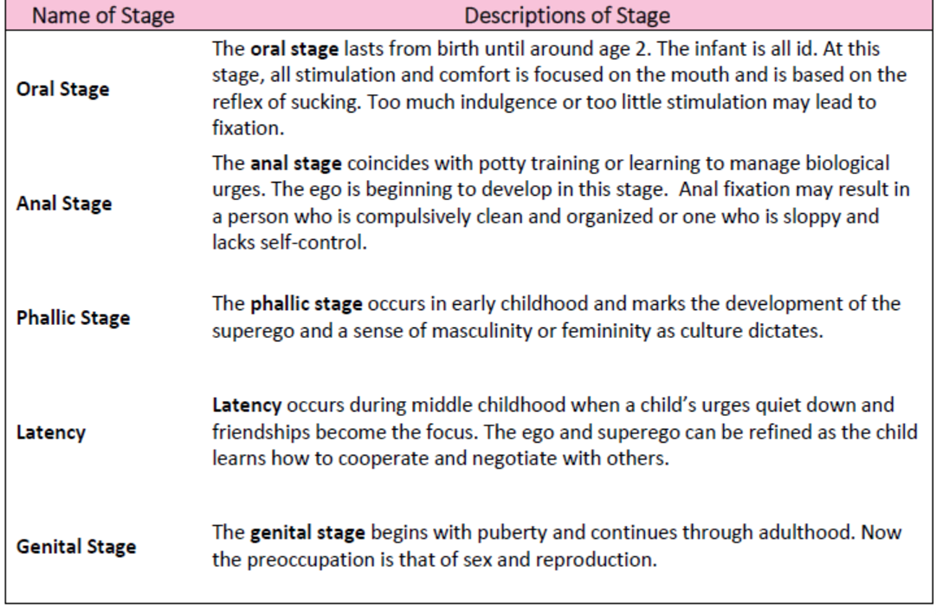

Psychosexual Stages

Freud’s psychosexual stages of development are presented in the table below. At any of these stages, the child might become “stuck” or fixated if a caregiver either overly indulges or neglects the child’s needs. A fixated adult will continue to try and resolve this later in life. Examples of fixation are given after the presentation of each stage.

Freud’s Psychosexual Stages

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is very difficult to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions is unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which elaborate and modify subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenges to Freud’s views.

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) and Psychosocial Theory[7]

Erikson suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior in his theory of psychosocial development. Erikson was a student of Freud’s but emphasized the importance of the ego, or conscious thought, in determining our actions. In other words, he believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. We know what motivates us and we consciously think about how to achieve our goals. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.

Erikson expanded on his Freud’s by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968).

He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the id. We make conscious choices in life and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

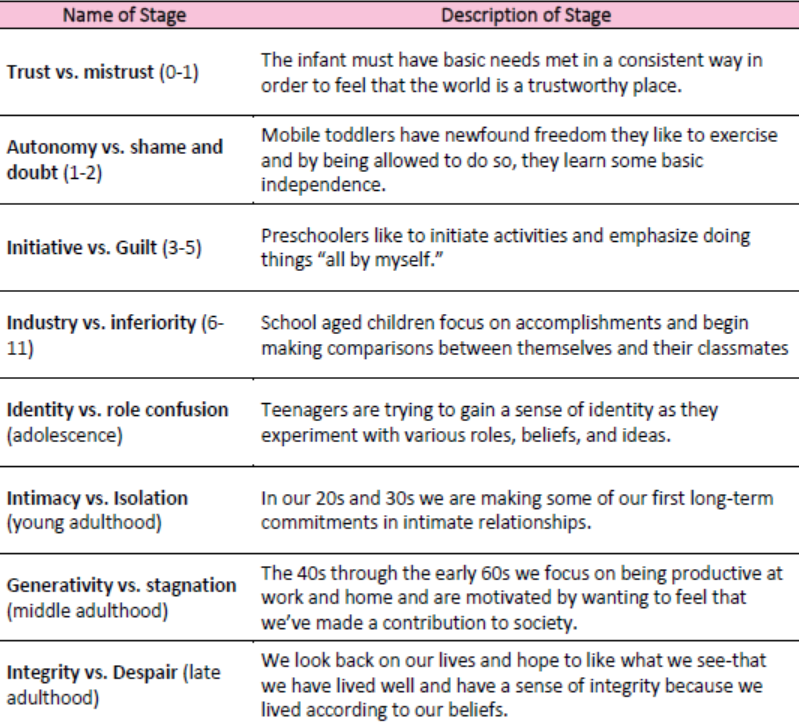

Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living. Here is a brief overview of the eight stages:

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or “crises” can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

Behaviorist

While Freud and Erikson looked at what was going on in the mind, behaviorists rejected any reference to mind and viewed overt and observable behavior as the proper subject matter of psychology. Through the scientific study of behavior, it was hoped that laws of learning could be derived that would promote the prediction and control of behavior.

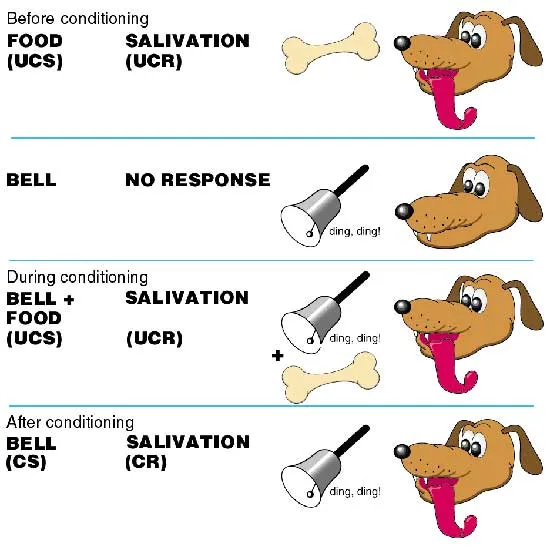

Ivan Pavlov (1870-1937) and Classical Conditioning[8] and Classical Conditioning with Animals

Ivan Pavlov was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. One possible explanation for this phenomenon would be that the dog learned that food comes after the bell.

Pavlov began to experiment with this concept of classical conditioning. He began to ring a bell, for instance, prior to introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus. The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response. Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and one is learned (conditioned).

Summary of Classical Conditioning Process (Animals)

Pavlovian Conditioning of a dog to salivate upon hearing a bell.

To summarize, classical conditioning (later developed by Watson, 1913) involves learning to associate an unconditioned stimulus that already brings about a particular response (i.e., a reflex) with a new (conditioned) stimulus, so that the new stimulus brings about the same response.

The unconditioned stimulus (or UCS) is the object or event that originally produces the reflexive /natural response. The response to this is called the unconditioned response (or UCR). The neutral stimulus (NS) is a new stimulus that does not produce a response. Once the neutral stimulus has become associated with the unconditioned stimulus, it becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS). The conditioned response (CR) is the response to the conditioned stimulus.[9]

Now, let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson.[10]

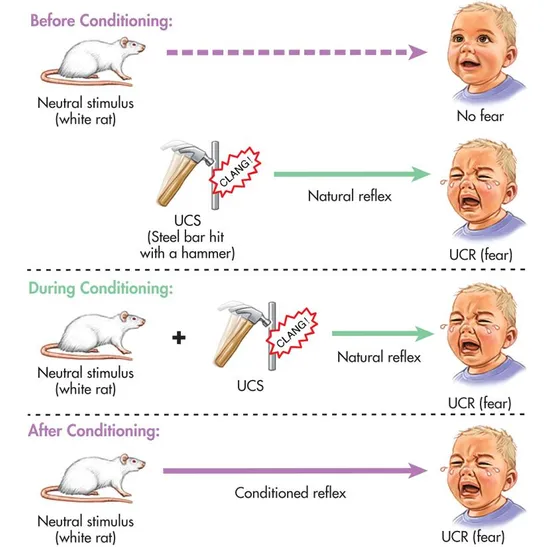

John B. Watson (1878-1958) and Classical Conditioning[11] and Classical Conditioning in Humans

Watson believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public. He tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18-month-old boy named “Little Albert”. Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced. Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired, if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and in magazines and gained a lot of popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order. [12]

Summary of Classical Conditioning Process (Humans)

Watson’s conditioning of Little Albert to fear a white rat. [13]

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, looks at the way the consequences of a behavior increase or decrease the likelihood of a behavior occurring again. So, let’s look at this a bit more.[14]

B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) and Operant Conditioning[15] and Operant Conditioning in Animals and Humans

Skinner (1904-1990), who brought us the principles of operant conditioning, suggested that reinforcement is a more effective means of encouraging a behavior than is punishment. By focusing on strengthening desirable behavior, we have a greater impact than if we emphasize what is undesirable.

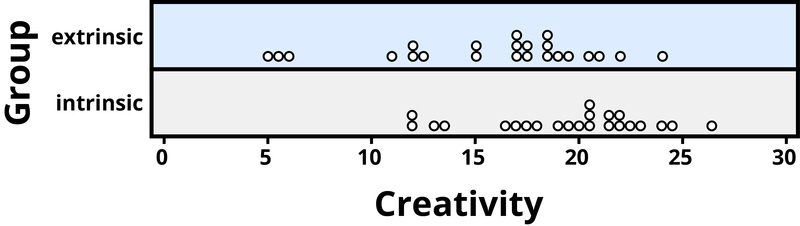

Reinforcement is the process by which a consequence increases the probability of a behavior that it follows. A reinforcer is a specific stimulus or situation that encourages the behavior that it follows. Intrinsic or primary reinforcers are reinforcers that have innate reinforcing qualities. These kinds of reinforcers are not learned and satisfy a biological need. Water, food, sleep, shelter, sex, pleasure, and touch, among others, are primary reinforcers. Swimming in a cool lake on a very hot day would be innately reinforcing because the water would cool the person off (a physical need), as well as provide pleasure. Extrinsic or secondary reinforcers have no inherent value and only have reinforcing qualities when linked with primary reinforcers. They can be traded in for what is ultimately desired. Praise, when linked to affection, is one example of a secondary reinforcer. Another example is money, which is only worth something when you can use it to buy other things—either things that satisfy basic needs (food, water, shelter—all primary reinforcers) or other secondary reinforcers. Extrinsic or secondary reinforcers are things that have a value not immediately understood.

Positive reinforcement occurs when the addition of a stimulus strengthens behavior. For example, positively reinforcing a child with the addition of a cookie for cleaning up will likely make encourage that behavior in the future. Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, occurs when removing a desired stimulus (or preventing access to it) strengthens behavior. For example, an alarm clock makes a very unpleasant, loud sound when it goes off in the morning. As a result, one gets up and turns it off. Therefore, getting up from bed is negatively reinforced through the termination of the aversive sound.

Punishmentis the process by which there decrease in the probability of behavior as a result of the consequence that follows it. Positive punishment occurs when the addition of an unpleasant or painful stimulus weakens behavior. For example, if a child is naughty and receives a spanking, the child will be less likely to misbehave in the future. Negative punishment, on the other hand, weakens a behavior through the removal of a desirable stimulus or preventing access to it. For example, a child who misbehaves and as a result has their favorite toy will be less likely to misbehave in the future. Punishment is often less effective than reinforcement for several reasons. It doesn’t indicate the desired behavior, it may result in suppressing rather than stopping a behavior, (in other words, the person may not do what is being punished when you’re around, but may do it often when you leave), and a focus on punishment can result in not noticing when the person does well.

Examples of Operant Conditioning Using Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Positive and Negative Punishers

| | POSITIVE

(Receive a Stimulus) |

NEGATIVE

(Stimulus Gets Taken Away) |

| REINFORCER

(Probability of Behavior Increases) |

Infant says “Mama” and mother claps her hands, smiles, and says, “very good, yes Mama!” The infant likes seeing the mother perform this way so continues to say “Mama.” | Infant’s diaper is wet or dirty, so infant cries. Someone comes and changes the diaper, thereby reducing the discomfort. The next time the child is uncomfortable, the child will cry. |

| PUNISHER

(Probability of Behavior Decreases) |

Child pulls the dog’s tail and the dog growls at the child. The child becomes frightened and does not pull the dog’s tail again. | Child behaves badly and his toy is taken away. The child learns that particular behavior is unacceptable and doesn’t want to lose the toy again, so the behavior is decreased or eliminated. |

Not all behaviors are learned through association or reinforcement. Many of the things we do are learned by watching others. This is addressed in social learning theory.[16]

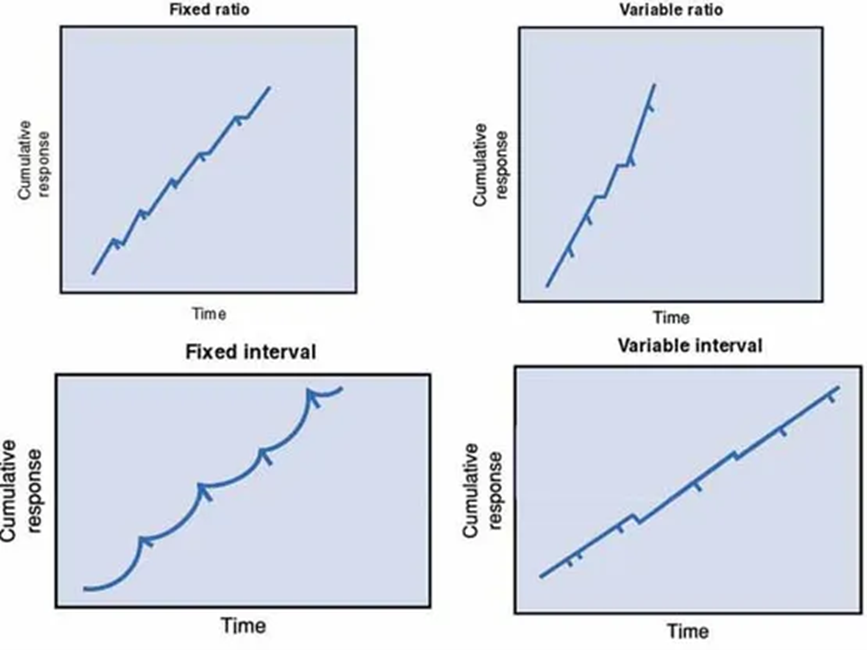

Schedules of Reinforcement

Imagine a rat in a “Skinner box.” In operant conditioning, if no food pellet is delivered immediately after the lever is pressed then after several attempts the rat stops pressing the lever (how long would someone continue to go to work if their employer stopped paying them?). The behavior has been extinguished.

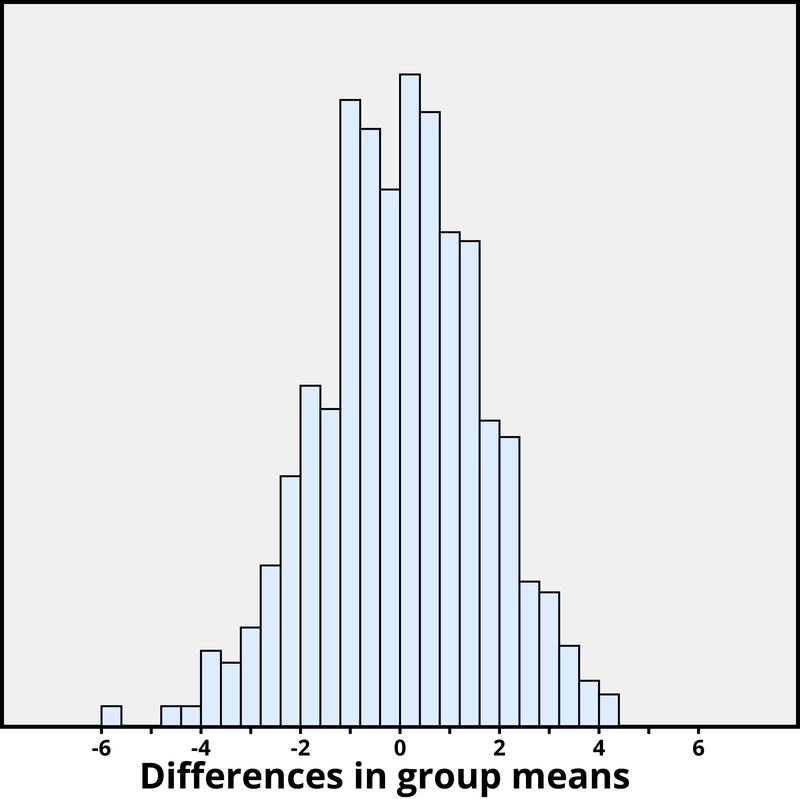

Behaviorists discovered that different patterns or schedules of reinforcement had different effects on the speed of learning and extinction. Ferster and Skinner (1957) devised different ways of delivering reinforcement and found that this had effects on

- The Response Rate – The rate at which the rat pressed the lever (i.e., how hard the rat worked).

- The Extinction Rate – The rate at which lever pressing dies out (i.e., how soon the rat gave up).

Skinner found that the type of reinforcement which produces the slowest rate of extinction (i.e., people will go on repeating the behavior for the longest time without reinforcement) is variable-ratio reinforcement. The type of reinforcement which has the quickest rate of extinction is continuous reinforcement.

| Response rate

Extinction rate |

slow | fast | |

| slow |

Variable Interval Reinforcement: Providing one correct response has been made, reinforcement is given after an unpredictable amount of time has passed, e.g., on average every 5 minutes. An example is a self-employed person being paid at unpredictable times. |

||

| medium |

Fixed Interval Reinforcement:One reinforcement is given after a fixed time interval providing at least one correct response has been made. An example is being paid by the hour. Another example would be every 15 minutes (half hour, hour, etc.) a pellet is delivered (providing at least one lever press has been made) then food delivery is shut off. |

Fixed Ratio Reinforcement:Behavior is reinforced only after the behavior occurs a specified number of times. e.g., one reinforcement is given after every so many correct responses, e.g., after every 5th response. For example, a child receives a star for every five words spelled correctly. |

|

| fast |

continuous reinforcementAn animal/human is positively reinforced every time a specific behavior occurs, e.g., every time a lever is pressed a pellet is delivered, and then food delivery is shut off. |

Variable Ratio Reinforcement:Behavior is reinforced after an unpredictable number of times. For examples gambling or fishing. |

Graphic Representation of Schedules of Reinforcement

Each dash indicates the point where reinforcement is given. [18]

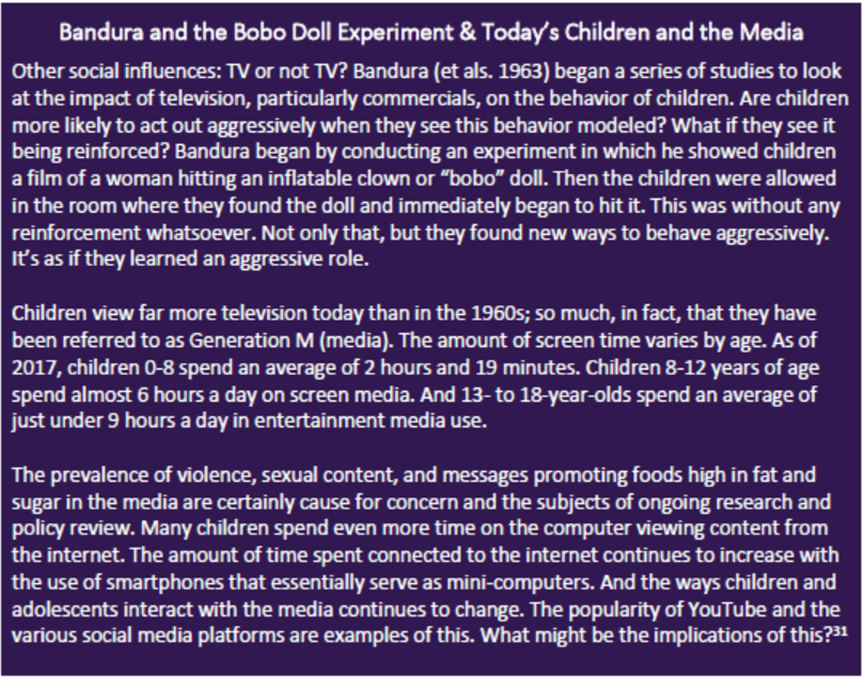

Albert Bandura (1925-2021) and Social Learning Theory[19] and Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to the ways in which many of our actions are not learned through conditioning; rather, they are learned by watching others (1977). Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation.

Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by observing others model their behavior and then imitating or copying that behavior. A kindergartner on his or her first day of school might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role-models. Sometimes we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behavior because we hope it will pay off for us as well. This is referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, Ross and Ross, 1963).

Bandura (1986) suggests that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us, and we create our environment. [20]

Cognitive Developmental Theories

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) and Theory of Cognitive Development[23]

Jean Piaget is one of the most influential cognitive theorists, and in the later modules we will discuss his work and his legacy in much more detail. Piaget was inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out the ways in which children’s thought differs from that of adults. His interest in this area began when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers. He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time through maturation. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Piaget believed our desire to understand the world comes from a need for cognitive equilibrium. This is an agreement or balance between what we sense in the outside world and what we know in our minds. If we experience something that we cannot understand, we try to restore the balance by either changing our thoughts or by altering the experience to fit into what we do understand. Perhaps you meet someone who is very different from anyone you know. How do you make sense of this person? You might use them to establish a new category of people in your mind or you might think about how they are similar to someone else.

A schema or schemes are categories of knowledge. They are like mental boxes of concepts. A child has to learn many concepts. They may have a scheme for “under” and “soft” or “running” and “sour”. All of these are schema. Our efforts to understand the world around us lead us to develop new schema and to modify old ones.

One way to make sense of new experiences is to focus on how they are similar to what we already know. This is assimilation. So, the person we meet who is very different may be understood as being “sort of like my brother” or “his voice sounds a lot like yours.” Or a new food may be assimilated when we determine that it tastes like chicken!

Another way to make sense of the world is to change our mind. We can make a cognitive accommodation to this new experience by adding new schema. This food is unlike anything I’ve tasted before. I now have a new category of foods that are bitter-sweet in flavor, for instance. This is accommodation. Do you accommodate or assimilate more frequently? Children accommodate more frequently as they build new schema. Adults tend to look for similarity in their experience and assimilate. They may be less inclined to think “outside the box.”

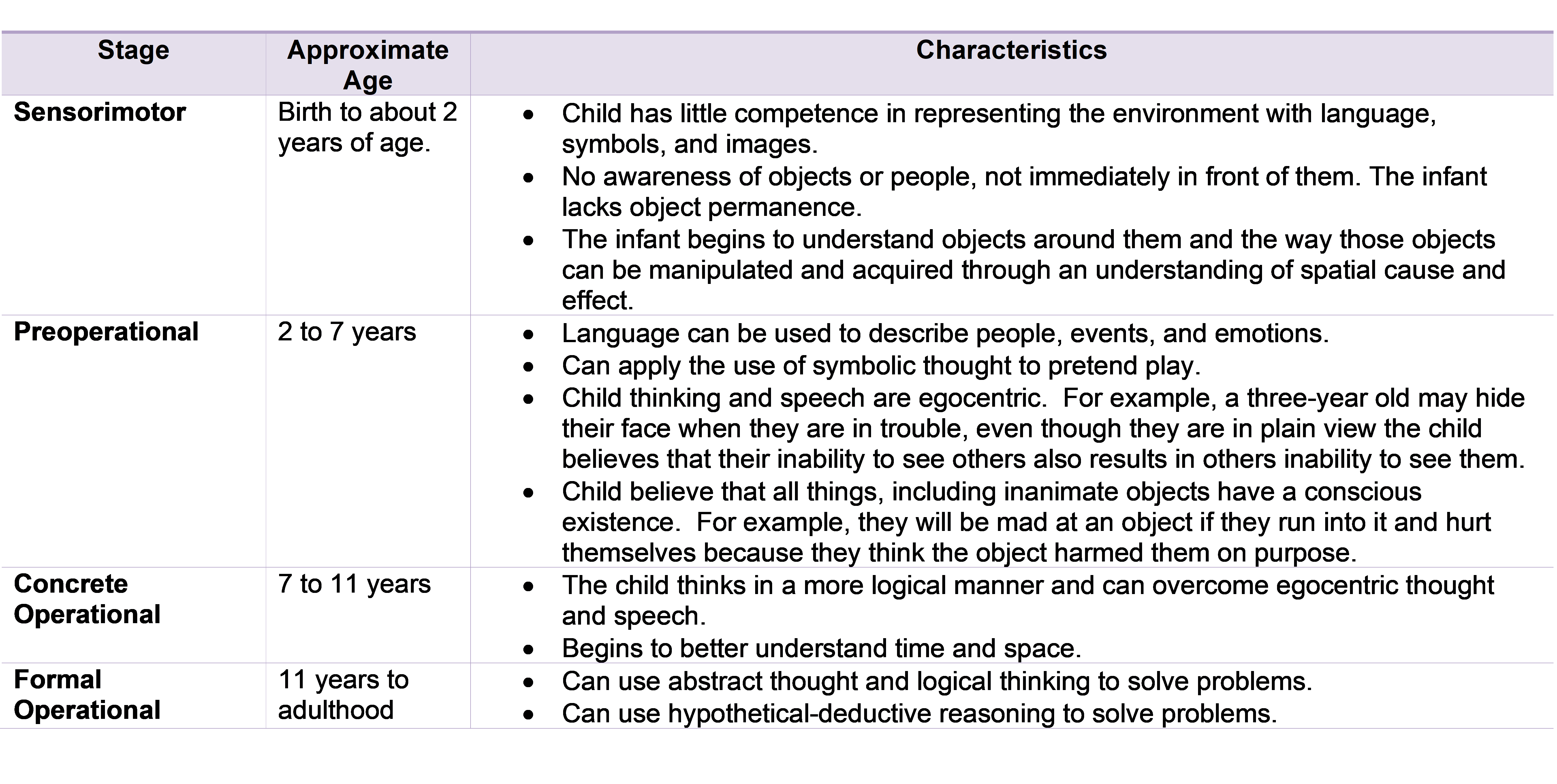

Piaget suggested different ways of understanding that are associated with maturation. He divided this understanding into the following four stages which will be discussed in much more detail in Chapter 7:

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development [24]

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing the role that physical maturation plays in cognitive development and in underestimating the role that culture and interaction (or experience) plays in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children are able to do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances.[25]

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and Sociocultural Theory[26]

Lev Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed with Piaget (this difference will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 7) in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development.[27]

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you all through the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do-you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern day educators.[28]

Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky

Vygotsky concentrated more on the child’s immediate social and cultural environment and his or her interactions with adults and peers. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities. We will elaborate on the two theories in later modules [29]

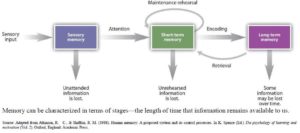

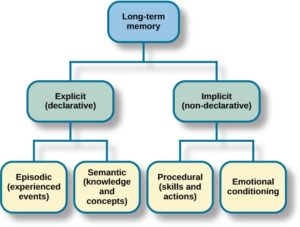

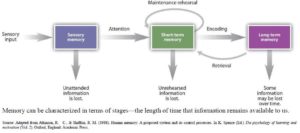

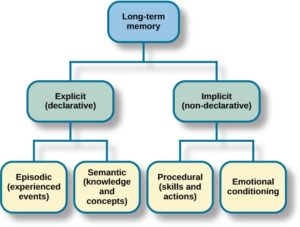

Information Processing

Information Processing is not the work of a single theorist but based on the ideas and research of several cognitive scientists studying how individuals perceive, analyze, manipulate, use, and remember information. This approach assumes that humans gradually improve in their processing skills; that is, cognitive development is continuous rather than stage-like. The more complex mental skills of adults are built from the primitive abilities of children. We are born with the ability to notice stimuli, store, and retrieve information. Brain maturation enables advancements in our information processing system. At the same time, interactions with the environment also aid in our development of more effective strategies for processing information.[30]

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) and Ecological Systems Theory[31]

Bronfenbrenner offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development. Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development.[32] The individual is impacted by several systems including:

- Microsystem includes the individual’s setting and those who have direct, significant contact with the person, such as parents or siblings. The input of those is modified by the cognitive and biological state of the individual as well. These influence the person’s actions, which in turn influence systems operating on him or her.

- Mesosystem includes the larger organizational structures, such as school, the family, or religion. These institutions impact the microsystems just described. The philosophy of the school system, daily routine, assessment methods, and other characteristics can affect the child’s self-image, growth, sense of accomplishment, and schedule thereby impacting the child, physically, cognitively, and emotionally.

- Exosystem includes the larger contexts of community. A community’s values, history, and economy can impact the organizational structures it houses. Mesosystems both influence and are influenced by the exosystem.

- Macrosystem includes the cultural elements, such as global economic conditions, war, technological trends, values, philosophies, and a society’s responses to the global community.

- Chronosystem is the historical context in which these experiences occur. This relates to the different generational time periods previously discussed, such as the baby boomers and millennials.

In sum, a child’s experiences are shaped by larger forces, such as the family, schools, religion, culture, and time period. Bronfenbrenner’s model helps us understand all the different environments that impact each one of us simultaneously. Despite its comprehensiveness, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory is not easy to use. Taking into consideration all the different influences makes it difficult to research and determine the impact of all the different variables (Dixon, 2003). Consequently, psychologists have not fully adopted this approach, although they recognize the importance of the ecology of the individual.[33]

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory[34]

Conclusion

Many early theories of human development were created and popularized in the early 1900s. These are referred to as stage theories because they present development as occurring in stages. The assumption is that once one stage is completed, a person moves into the next stage and that stages tend to occur only once. Some examples of stage theories that we will be studying include Freud’s psychosexual stages, Erikson’s psychosocial stages, and Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, to name a few.

These theories are appealing in a way because they provide the ability to predict what will happen next and they allow us to attribute behavior to a person’s being ‘in a stage’. These theories offered the security of understanding human behavior in a time of rapid change during industrialization in the early 1900s. Science seemed to be laying a predictable groundwork we could rely upon. But these early theories also implied that those who did not progress through stages in the predictable way were delayed somehow and this led to the idea that development had to occur in a patterned way.

Today we understand that development does not occur in a straight line. Sometimes we change in many directions depending on our experiences and surroundings. For example, there can be growth and decline in cognitive functioning at any age depending on nutrition, health, activity, and stimulation. And that both nature (heredity) and nurture (the environment) shape our abilities throughout life. Some things about us are continuous such as our temperament or sense of self, perhaps. And we may revisit a stage of life more than once. For instance, Erikson suggests that we struggle with trust as infants and then begin to focus more on independence or autonomy. But if we are in circumstances in which our independence is jeopardized, such as becoming physically dependent, we may struggle with trust again. Keep these thoughts in mind as we explore stage theories in our next lesson.

The study of human development is based on research. The next chapter looks at some of the different types of research methods used to understand development. In other words, how do we know what we know?[35]

Media Attributions

- Private: John Locke

- Private: Roussou

- Private: Image 4 Freud

- Private: Image 5 Iceburg Id Ego and Superego

- Private: Image 6 Freud’s Psychosexual Stages

- Private: Image7 Erikson

- Private: Image 8 Table Eriksons Psychosocial Theory

- Private: Item 9 Pavlov

- Private: Item 10 Classical Conditioning Chart

- Private: Item 11 Watson

- Private: Item 12 Classical Conditioning Human

- Private: Item 13 Skinner

- Private: Item 14 Schedules of Reinforcement

- Private: Item 15 Bandura

- Private: Item 16 Blurb on Bandura and Bobo Doll Experiment

- Private: Item 17 Piaget

- Private: Item 18B New Version of Piagetian Stages Chart

- Private: Item 19 Vygotsky

- Private: Item 20 Bronfenbrenner

- Private: Item 21 Brofenbrenner Ecological System

- Image of John Locke by Godfrey Kneller and is public domain ↵

- Image of Rousseau from Wikimedia Commons and is public domain ↵

- Image of Freud is public domain ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- McLeod, S. A. (2019, September 25). Id, ego and superego. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/psyche.html. Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- Image from McLeod, S. A. (2019, September 25). Id, ego and superego. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/psyche.html. Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 Text by Maria Pagano ↵

- Image of Erikson is public domain ↵

- Image of Pavlov is in the public domain ↵

- Text and image by McLeod, S. A. (2018, October 08). Pavlov's dogs. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/pavlov.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image of Watson is public domain ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image by McLeod, S. A. (2018, October 08). Pavlov's dogs. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/pavlov.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image of Skinner is public domain ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano and Marie Parnes) ↵

- McLeod, S. A. (2018, January, 21). Skinner - operant conditioning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- McLeod, S. A. (2018, January, 21). Skinner - operant conditioning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- Image of Albert Bandura is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Exploring Behavior by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0Rasmussen, Eric (2017, Oct 19). Screen Time and Kids: Insights from a New Report. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/parents/thrive/screen-time-and-kids-insights-from-a-new-report ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image is in the public domain and taken from Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Original document created by Jordy von Hippel and taken from her Developmental Psychology WordPress Blog. No copyright information provided on site. Material updated by Maria Pagano ↵

- Lecture Transcript: Developmental Theories by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Jennifer Paris) ↵

- Image by The Vigotsky Project is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Exploring Cognition by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Exploring Cognition by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Image by Marco Vicente González is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Image by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lecture Transcript: Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

A child’s status among their peers will influence their membership in peer groups and their ability to make friends. Sociometric status is a measurement that reflects the degree to which someone is liked or disliked by their peers as a group. In developmental psychology, this system has been used to examine children's status in peer groups, its stability over time, the characteristics that determine it, and the long-term implications of one's popularity or rejection by peers.

The most commonly used sociometric system, developed by Coie & Dodge (1988), asks children to rate how much they like or dislike each of their classmates and uses these responses to classify them into five groups.

Figure 11.3.1. Sociometric peer statuses.

Popular adolescents are those liked by many of their peers and disliked by few. These individuals are skilled at social interactions and maintain positive peer relationships. They tend to be cooperative, friendly, sociable, and sensitive to others. They are capable of being assertive without being aggressive, thus can get what they want without harming others. Among this group, there may be distinct levels of popularity:

- Accepted teens are the most common sub-group among the popular. While they are generally well-liked, they are not as magnetic as the very popular kids.

- Very popular teens are highly charismatic and draw peers to them.

Rejected teens are designated as rejected if they receive many negative nominations and few positive nominations. These individuals often have poor academic performance and more behavior problems in school. They are also at higher risk for delinquent behaviors and legal problems. These kids are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, conduct disorder, and substance abuse. They tend to be isolated, lonely and are at risk for depression. Rejected youth can be categorized into two types:

- Aggressive-rejected teens display hostile and threatening behavior, are physically aggressive, and disruptive. They may bully others, withhold friendship, ignore and exclude others. While they are lacking, they tend to overestimate their social competence.

- Withdrawn-rejected teens are socially withdrawn, wary, timid, anxious in social situations, and lack confidence. They are at risk of being bullied.

Individuals that are liked by many peers, but also dislike by many are designated as controversial. This group may possess characteristics of both the popular and the rejected group. These individuals tend to be aggressive, disruptive, and prone to anger. However, they may also be cooperative and social. They are often socially active and a good group leader. Their peers often view them as arrogant and snobbish.

The neglected teens are designated as neglected if they receive few positive or negative nominations. These children are not especially liked or disliked by peers and tend to go unnoticed. As a result, they may be isolated and especially avoid confrontation or aggressive interactions. This group does tend to do well academically.

Finally, the average teens are designated as such because they receive an average number of both positive and negative nominations. They are liked by a small group of peers, but not disliked by very many.

Figure 11.3.2. Sociometric peer statuses and characteristics.

Popularity

What makes an adolescent popular? Several physical, cognitive, and behavioral factors impact popularity. First, adolescents that are perceived to be physically attractive tend to be more popular among their peers. Cognitive traits matter too. Individuals that demonstrate higher intelligence and do well academically tend to be more liked. Also, those that can take another’s perspective and demonstrate social problem-solving skills are favored. Teens that can manage their emotions and behave appropriately gain higher status. Finally, teens like peers that are confident without being conceited.

Interventions

What can be done to help those adolescents that are not well-liked? For neglected teens, social skills training and encouraging them to join activities can help them become noticed by their peers and make friends. For rejected teens, they may need support to help with anger management, to overcome anxiety, and cope with depression. This group can also benefit from social skills training to learn social competence and gain confidence.

Culture

As you might imagine, peer relationships are shaped by a wide range of contextual factors, and their development is not universal across all environments. One of the most significant influences is culture, which plays a key role in shaping how children and adolescents form and maintain relationships with their peers.

For example, in cultures that emphasize individualism—such as the United States—peer relationships tend to be more intimate and emotionally expressive. U.S. students often form close, dyadic friendships that are highly influential in shaping their social and emotional development. These friendships typically involve high levels of self-disclosure, loyalty, and mutual support.

In contrast, in cultures that emphasize collectivism—such as Indonesia—peer relationships are often broader and more group-oriented. Indonesian students may interact with a wider network of peers, placing greater value on group harmony, cooperation, and shared responsibility rather than deep individual closeness. While these relationships may seem less emotionally intense from a Western perspective, they reflect a strong sense of belonging within the peer group.

These differences highlight how cultural values shape not only the structure of peer relationships but also the expectations, behaviors, and emotional expressions within them. Recognizing these cultural variations helps us understand that peer development is deeply embedded within social and cultural contexts.

Family

In addition to culture, family also plays an important role in shaping children's peer relationships. Parents and caregivers can exert both direct and indirect influences. Directly, families influence who children associate with—for example, by arranging playdates or enrolling them in specific schools or activities. Indirectly, the neighborhood a family chooses can shape the peer group available to the child, especially in early and middle childhood, when friendships are often formed based on physical proximity.

Families also influence peer relationships through their impact on children’s social skills and behavior. Children observe how their parents interact with others and often model these behaviors. Furthermore, parenting styles that support socioemotional development—such as warm, responsive caregiving—are associated with children who possess better social skills, emotional regulation, and empathy (Moroni et al., 2019). These skills, in turn, enhance children's ability to build and maintain positive peer relationships.

Social Media

Finally, with the rise of technology and social media, peer relationships have undergone significant transformation. Social media increases the frequency and immediacy of peer interactions, making it easier for children and adolescents to stay connected. This can have positive effects, such as providing immediate social support, but may also lead to negative outcomes, like increased co-rumination or social comparison. Moreover, social media enables the formation of entirely online friendships, expanding the peer network beyond school and neighborhood boundaries. As a result, peer relationships are no longer limited by geographical proximity and are increasingly shaped by the digital environment, which can both enhance and complicate children's social experiences.

Impact of peer relationship

Throughout this book, we have emphasized the importance of peers in children’s development. Just like the family, peer relationships play a critical role across multiple domains of development. In fact, as children grow older—particularly after entering the formal school system—peer relationships become increasingly influential. Peers impact development in many areas, especially on their cognitive and socioemotional development.

As discussed in the section on academic achievement, peer influence plays a significant role in children’s learning. Participation in structured learning environments—such as collaborative study groups or classroom-based peer interactions—is positively associated with academic success. These settings not only reinforce academic skills but also foster motivation and engagement. As children mature, they become more likely to seek academic support from peers rather than family members, highlighting the growing importance of peer networks in educational contexts.

In addition to cognitive development, positive peer relationships are crucial for socioemotional development. Through peer interactions, children learn to navigate social dynamics, resolve conflicts, practice cooperation, and regulate their emotions. These experiences help them build essential social skills that contribute to emotional resilience and interpersonal competence. Children with supportive peer relationships tend to be more emotionally stable, exhibit higher self-esteem, and report greater life satisfaction.

Conversely, children who experience peer rejection or social exclusion are at greater risk for emotional difficulties. Repeated rejection or bullying can lead to heightened stress, which may contribute to serious consequences such as anxiety, depression, and poor academic outcomes. Therefore, fostering healthy peer relationships is essential for promoting well-rounded development and long-term well-being.

A child’s status among their peers will influence their membership in peer groups and their ability to make friends. Sociometric status is a measurement that reflects the degree to which someone is liked or disliked by their peers as a group. In developmental psychology, this system has been used to examine children's status in peer groups, its stability over time, the characteristics that determine it, and the long-term implications of one's popularity or rejection by peers.

The most commonly used sociometric system, developed by Coie & Dodge (1988), asks children to rate how much they like or dislike each of their classmates and uses these responses to classify them into five groups.

Figure 11.3.1. Sociometric peer statuses.

Popular students are those liked by many of their peers and disliked by few. These individuals are skilled at social interactions and maintain positive peer relationships. They tend to be cooperative, friendly, sociable, and sensitive to others. They are capable of being assertive without being aggressive, thus can get what they want without harming others. Among this group, there may be distinct levels of popularity:

- Accepted students are the most common sub-group among the popular. While they are generally well-liked, they are not as magnetic as the very popular kids.

- Very popular students are highly charismatic and draw peers to them.

Rejected students are designated as rejected if they receive many negative nominations and few positive nominations. These individuals often have poor academic performance and more behavior problems in school. They are also at higher risk for delinquent behaviors and legal problems. These kids are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, conduct disorder, and substance abuse. They tend to be isolated, lonely and are at risk for depression. Rejected youth can be categorized into two types:

- Aggressive-rejected students display hostile and threatening behavior, are physically aggressive, and disruptive. They may bully others, withhold friendship, ignore and exclude others. While they are lacking, they tend to overestimate their social competence.

- Withdrawn-rejected students are socially withdrawn, wary, timid, anxious in social situations, and lack confidence. They are at risk of being bullied.

Individuals that are liked by many peers, but also dislike by many are designated as controversial. This group may possess characteristics of both the popular and the rejected group. These individuals tend to be aggressive, disruptive, and prone to anger. However, they may also be cooperative and social. They are often socially active and a good group leader. Their peers often view them as arrogant and snobbish.

The neglected students are designated as neglected if they receive few positive or negative nominations. These children are not especially liked or disliked by peers and tend to go unnoticed. As a result, they may be isolated and especially avoid confrontation or aggressive interactions. This group does tend to do well academically.

Finally, the average students are designated as such because they receive an average number of both positive and negative nominations. They are liked by a small group of peers, but not disliked by very many.

Figure 11.3.2. Sociometric peer statuses and characteristics.

Popularity

What makes an adolescent popular? Several physical, cognitive, and behavioral factors impact popularity. First, adolescents that are perceived to be physically attractive tend to be more popular among their peers. Cognitive traits matter too. Individuals that demonstrate higher intelligence and do well academically tend to be more liked. Also, those that can take another’s perspective and demonstrate social problem-solving skills are favored. Teens that can manage their emotions and behave appropriately gain higher status. Finally, teens like peers that are confident without being conceited.

Interventions

What can be done to help those adolescents that are not well-liked? For neglected teens, social skills training and encouraging them to join activities can help them become noticed by their peers and make friends. For rejected teens, they may need support to help with anger management, to overcome anxiety, and cope with depression. This group can also benefit from social skills training to learn social competence and gain confidence.

Gender Development Theories

Gender refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviors, expressions, and identities associated with being male, female, or non-binary. It differs from sex, which is a biological term referring to physical and reproductive characteristics. Gender plays a significant role in our daily lives, shaping how we see ourselves and others. Multiple theories have been proposed to explain how children come to understand gender and how it becomes a central dimension for categorizing people and even objects.

Intergroup Theory

Intergroup theory suggests that while young children can perceive gender differences, they do not automatically attach meaning or stereotypes to those differences. However, adults often use gendered language and emphasize gender distinctions, which signals to children that gender is an important category. Over time, this emphasis leads children to form stereotypes based on gender. For example, a young girl may notice differences between herself and her brother, but she might not see those differences as meaningful unless her parents treat them differently—for instance, assigning her brother physical chores like mowing the lawn while she is asked to do indoor tasks like washing dishes.

Gender Schema Theory

Gender schema theory, rooted in Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory, views children as active learners who build mental frameworks—or schemas—to understand gender as a social category. Children observe and categorize behaviors, roles, and attributes associated with gender, and over time, they assimilate new information into these schemas or adjust them through accommodation. This process helps refine their understanding of what is considered "appropriate" for each gender based on social input.

Social Learning Theory

Social learning theory, drawing from behaviorist principles, proposes that children learn gender roles through modeling, reinforcement, and punishment. Children observe the behaviors of adults and peers and imitate those they see as aligned with their own gender. They then adjust their behavior based on the feedback they receive. For example, if a young boy paints his nails like his mother and is punished or teased for it, he may internalize the idea that nail polish is not appropriate for boys, thus shaping his understanding of gender roles.

Throughout this book, we have mentioned the importance of peers. Just like family, peer relationship plays an important role in our development. Actually, as children gets older, especially after they entered the formal school system, peer relationship becomes more and more impactful. Peer relationship influences children's development in many dimensions but we will focus on their influence on children's cognitive development and socioemotional development.

Cognitive Development

As we discussed in the academic achievement, peers play an important role in children's academic achievement. Being part of a structured learning community, such as a study group is positively associated with children's academic performance. As children grows older, they are more and morel ik

Influence of family on children

The influence of family on children’s development is both profound and long-lasting. For instance, the quality of attachment formed in infancy can predict socioemotional outcomes well into adulthood (Groh & Fearon, 2017). Children who have a secure and positive relationship with their caregivers are more likely to develop strong social-emotional skills, display prosocial behavior, form high-quality friendships, and be well-liked by peers. In contrast, children who lack a supportive caregiver relationship are at greater risk for difficulties in these areas.

Parental influence extends beyond socioemotional development and plays a crucial role in shaping children’s cognitive growth as well. The home environment and parents’ attitudes can significantly impact a child’s learning. For example, research has shown that children whose parents are anxious or avoidant about math tend to perform worse in the subject, compared to those whose parents express confidence and a positive attitude toward math (Casada et al., 2015) . This highlights the powerful role that parental beliefs and behaviors play in shaping children's academic outcomes.

While peers become increasingly important as children grow older, family continues to play a crucial role in children's development throughout middle childhood and adolescence. The influence of caregivers remains strong, shaping children's emotional well-being, values, academic motivation, and overall development. It is important to recognize the enduring impact of the family environment, and caregivers should strive to provide supportive, responsive, and nurturing conditions that promote healthy growth and adjustment during these formative years.

As mentioned previously, Gender identity is one’s self-conception of their gender. Sex is the term to refer to the biological differences between males and females, such as the genitalia and genetic differences. While gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of women and men, such as norms, roles, and relationships between groups of women and men. Cisgender is an umbrella term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex, while transgender is a term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity does not correspond with their birth sex.

As mentioned previously, Gender identity is one’s self-conception of their gender. Sex is the term to refer to the biological differences between males and females, such as the genitalia and genetic differences. While gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of women and men, such as norms, roles, and relationships between groups of women and men. Cisgender is an umbrella term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex, while transgender is a term used to describe people whose sense of personal identity does not correspond with their birth sex.

Gender expression, or how one demonstrates gender (based on traditional gender role norms related to clothing, behavior, and interactions), can be feminine, masculine, androgynous, or somewhere along a spectrum. Many adolescents use their analytic, hypothetical thinking to question traditional gender roles and expression. If their genetically assigned sex does not line up with their gender identity, they may refer to themselves as transgender, non-binary, or gender-nonconforming.

Fluidity and uncertainty regarding sex and gender are especially common during early adolescence when hormones increase and fluctuate, creating a difficulty of self-acceptance and identity achievement (Reisner et al., 2016). Gender identity is becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for males and females are evolving, and some adolescents may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty by adopting more stereotypic male or female roles (Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013). Those that identify as transgender or ‘other’ face even more significant challenges.

Biological Approach to Gender Identity Development

The biological approach explores how gender identity development is influenced by genetics, biological sex characteristics, brain development, and hormone exposure.

Humans usually have 23 pairs of chromosomes, each containing thousands of genes that govern various aspects of our development. The 23rd pair of chromosomes are called the sex chromosomes. This pair determines a person’s sex, among other functions. Most often, if a person has an XX pair, they will develop into a female, and if they have an XY pair, then they will be male.

Around the sixth week of prenatal development, the SRY gene on the Y chromosome signals the body to develop as a male. This chemical signal triggers a cascade of other hormones that will tell the gonads to develop into testes. If the embryo does not have a Y or the if, for some reason, the SRY gene is missing or not activate, then the embryo will develop female characteristics. The baby is born and lives as a female, but genetically her chromosomes are XY. Rat studies have found that the reverse is also possible. Researchers implanted the SRY gene in rats with XX chromosomes, and the result was male baby mice.

Individuals with atypical chromosomes may also develop differently than their typical XX or XY counterparts. These chromosomal abnormalities include syndromes where a person may have only one sex chromosome or three sex chromosomes. Turner’s Syndrome is a condition where a female has only one X chromosome (XO). This missing chromosome results in a female external appearance but lacking ovaries. These XO females do not mature through puberty like XX females and they may also have webbed skin around the neck. Cognitively, these females tend to have high verbal skills, poor spatial and math skills, and poor social adjustment.

Klinefelter’s Syndrome is a condition where a male has an extra X chromosome (XXY). This XXY combination results in male genitals, although their genitals may be underdeveloped even into adulthood. Even after puberty, they tend to have less body and facial hair and may develop breasts. From infancy, these children often have a passive, cooperative, and shy personality that remains into adulthood. Cognitively, they are often late to talk and have poor language and reading skills.

As we learned in the physical development chapter, sex hormones cause biological changes to the body and brain. While the same sex hormones are present in males and females, the amount of each hormone and the effect of that hormone on the body is different. Males have much higher levels of testosterone than females. In the womb, testosterone causes the development of male sex organs. It also impacts the hypothalamus, causing an enlarged sexually dimorphic nucleus, and results in the ‘masculinization’ of the brain. Around the same time, testosterone may contribute to greater lateralization of the brain, resulting in the two halves working more independently of each other. Testosterone also affects what we often consider male behaviors, such as aggression, competitiveness, visual-spatial skills, and higher sex drive.

Cognitive Approaches to Gender Identity Development

Cognitive Learning Theory

Cognitive learning theory states that children develop gender at their own levels. At each stage, the child thinks about gender characteristically. As a child moves forward through stages, their understanding of gender becomes more complex.

The following cognitive model, formulated by Kohlberg, asserts that children recognize their gender identity around age three but do not see it as relatively fixed until the ages of five to seven. This identity marker provides children with a schema, a set of observed or spoken rules for how social or cultural interactions should happen. Information about gender is gathered from the environment; thus, children look for role models to emulate maleness or femaleness as they grow.

Stage 1: Gender Labeling (2-3.5 years). The child can label their gender correctly.

Stage 2: Gender Stability (3.5-4.5 years). The child’s gender remains the same across time.

Stage 3: Gender Constancy (6 years). The child’s gender is independent of external features (e.g., clothing, hairstyle).

Once children form a basic gender identity, they start to develop gender schemas. These gender schemas are organized set of gender-related beliefs that influence behaviors. The formation of these schemas explains the process by which gender stereotypes become so psychologically ingrained in our society.

Gender Schema Theory

Sandra Bem’s Gender Schema Theory, rooted in Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory, views children as active learners who build mental frameworks—or schemas—to understand gender as a social category. Children observe and categorize behaviors, roles, and attributes associated with gender, and over time, they assimilate new information into these schemas or adjust them through accommodation. This process helps refine their understanding of what is considered "appropriate" for each gender based on social input. According to this theory, gender schemas can be organized into four general categories. The sex-type schema is the belief that gender matches biological sex. Sex-reversed schema is when gender is the opposite of biological sex. Possessing both masculine and feminine traits is an androgynous schema. While possessing few masculine or feminine traits is an undifferentiated schema.

Social Approaches to gender identity development

Social Learning Theory

Social Learning Theory is based on outward motivational factors that argue that if children receive positive reinforcement, they are motivated to continue a particular behavior. If they receive punishment or other indicators of disapproval, they are more motivated to stop that behavior. In terms of gender development, children receive praise if they engage in culturally appropriate gender displays and punishment if they do not. When aggressiveness in boys is met with acceptance or a “boys will be boys” attitude, but a girl’s aggressiveness earns them little attention, the two children learn different meanings for aggressiveness as it relates to their gender development. Thus, boys may continue being aggressive while girls may drop it out of their repertoire.

Intergroup Theory

Intergroup theory suggests that while young children can perceive gender differences, they do not automatically attach meaning or stereotypes to those differences. However, adults often use gendered language and emphasize gender distinctions, which signals to children that gender is an important category. Over time, this emphasis leads children to form stereotypes based on gender. For example, a young girl may notice differences between herself and her brother, but she might not see those differences as meaningful unless her parents treat them differently—for instance, assigning her brother physical chores like mowing the lawn while she is asked to do indoor tasks like washing dishes.

Transgender Identity Development

Individuals who identify with the role that is different from their biological sex are called transgender. Approximately 1.4 million U.S. adults or .6% of the population are transgender, according to a 2016 report (Flores et al., 2016).

Transgender individuals may choose to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy so that their physical being is better aligned with gender identity. They may also be known as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM). Not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies; many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as another gender. This expression is typically done by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to another gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to a different gender is not the same as identifying as transgender. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and it is not necessarily an expression against one’s assigned gender (APA 2008).

After years of controversy over the treatment of sex and gender in the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (Drescher 2010), the most recent edition, DSM-5, responded to allegations that the term “gender identity disorder” is stigmatizing by replacing it with “gender dysphoria.” Gender identity disorder as a diagnostic category stigmatized the patient by implying there was something “disordered” about them. Removing the word “disorder” also removed some of the stigmas while still maintaining a diagnosis category that will protect patient access to care, including hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery.

In the DSM-5, gender dysphoria is a condition of people whose gender at birth is contrary to the one with which they identify. For a person to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, there must be a marked difference between the individual’s expressed/experienced gender and the gender others would assign him or her, and it must continue for at least six months. In children, the desire to be of the other gender must be present and verbalized (APA, 2013). Changing the clinical description may contribute to greater acceptance of transgender people in society. A 2017 poll showed that 54% of Americans believe gender is determined by sex at birth, and 32% say society has “gone too far” in accepting transgender people; views are sharply divided along political and religious lines (Salam, 2018).

Many psychologists and the transgender community are now advocating an affirmative approach to transgender identity development. This approach advocates that gender non-conformity is not a pathology but a normal human variation. Gender non-conforming children do not systemically need mental health treatment if they are not “pathological.” However, care-givers of gender non-conforming children can benefit from a mixture of psycho-educational and community-oriented interventions. Some children or teens may benefit from counseling or other interventions to help them cope with familial or societal reactions to their gender-nonconformity.

Studies show that people who identify as transgender are twice as likely to experience assault or discrimination as non-transgender individuals; they are also one and a half times more likely to experience intimidation (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2010; Giovanniello, 2013). Trans women of color are most likely to be victims of abuse. There are also systematic aggressions, such as “deadnaming,” (whereby trans people are referred to by their birth name and gender), laws restricting transpersons from accessing gender-specific facilities (e.g., bathrooms), or denying protected-class designations to prevent discrimination in housing, schools, and workplaces. Organizations such as the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs and Global Action for Trans Equality work to prevent, respond to and end all types of violence against transgender and homosexual individuals. These organizations hope that by educating the public about gender identity and empowering transgender individuals, this violence will end.

Like other domains of identity, stage models for transgender identity development have helped describe a typical progression in identity formation. Lev’s Transgender Emergence Model looks at how trans people come to understand their identity. Lev is working from a counseling/therapeutic point of view, thus this model talks about what the individual is going through and the responsibility of the counselor.

Stage 1: Awareness. In this first stage of awareness, gender-variant people are often in great distress; the therapeutic task is the normalization of the experiences involved in emerging as transgender.

Stage 2: Seeking Information/Reaching Out. In the second stage, gender-variant people seek to gain education and support about transgenderism; the therapeutic task is to facilitate linkages and encourage outreach.

Stage 3: Disclosure to Significant Others. The third stage involves the disclosure of transgenderism to significant others (spouses, partners, family members, and friends); the therapeutic task involves supporting the transgender person’s integration in the family system.

Stage 4: Exploration (Identity & Self-Labeling). The fourth stage involves the exploration of various (transgender) identities; the therapeutic task is to support the articulation and comfort with one’s gendered identity.

Stage 5: Exploration (Transition Issues & Possible Body Modification). The fifth stage involves exploring options for transition regarding identity, presentation, and body modification; the therapeutic task is the resolution of the decision and advocacy toward their manifestation.

Stage 6: Integration (Acceptance & Post-Transition Issues). In the sixth stage, the gender-variant person can integrate and synthesize (transgender) identity; the therapeutic task is to support adaptation to transition-related issues.

As we previously discussed, gender is distinct from sex. Gender refers to the social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral traits associated with being male, female, or another gender identity. Sex, in contrast, refers to biological characteristics, such as chromosomes, hormones, and reproductive anatomy. As children’s gender identity continues to develop, their understanding of the traits, roles, and expectations associated with different genders also evolves over time.

In general, younger children tend to hold rigid gender stereotypes, but this rigidity often decreases as they enter middle childhood. For example, one study found that while only 33.8% of 5-year-olds believed that objects like vacuum cleaners were for both men and women, that number increased to 87.8% among 11-year-olds (Banse et al., 2010). However, this flexibility may decline again during adolescence, a time when youth begin exploring identity more deeply and often conform more closely to traditional gender roles. A study by Alferi and colleagues (1996) found that gender flexibility peaked in grades 7–8 and declined afterward, suggesting a return to more rigid views during later adolescence.

Measuring gender stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are commonly measured by assessing whether youth categorize certain attributes as male- or female-typical (i.e., gender stereotypes) and whether they view it as acceptable for both genders to express those traits (i.e., gender flexibility). In recent years, researchers have also turned to implicit measures such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT) to capture unconscious gender biases. In these tasks, participants categorize words or images related to gender (e.g., "man," "woman") and domains (e.g., "math," "language"). In congruent trials, gender-stereotypical pairings are grouped together (e.g., male/math), while in incongruent trials, non-stereotypical pairings are grouped (e.g., female/math). If participants have implicit stereotypes (e.g., associating men more strongly with math), they tend to respond more slowly in the incongruent trials. Research has consistently shown that such implicit biases are common in both adolescents and adults.

Video 11.

What influences gender stereotype?